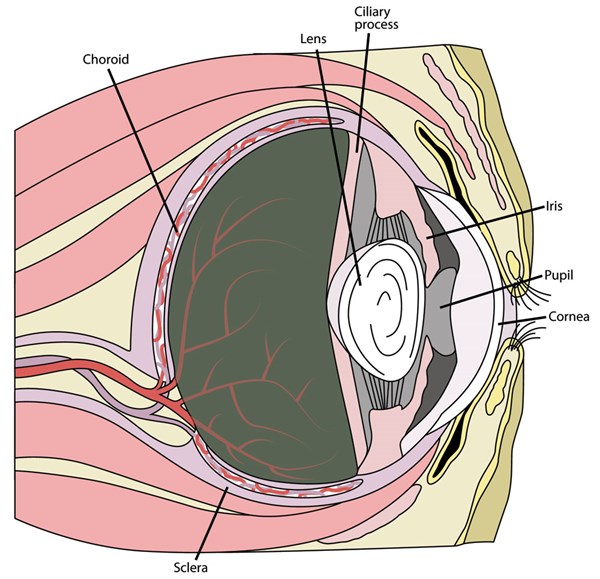

Uveitis is a term that refers to inflammation of the uvea. The uvea consists of the iris (the colored portion of the eye around the pupil), the ciliary body (which acts as a super filter of the blood to produce the fluid in the eye) and the choroid (which supplies blood to the back of the eye and to the important rods and cones responsible for vision). The ciliary body provides such a tight filter that no cells should actually have access to the eye. This lack of exposure to cells makes the eye an immune-privileged site, meaning that normally the immune system does not have access to the inside of the eye.

When there is an inflammatory event, such as trauma or infection of a corneal ulcer, inflammatory mediators called prostaglandins are released. Prostaglandins are responsible for the breakdown of the blood–eye barrier, allowing the cells of the immune system access to the eye. In a single event that does not last very long or with minor inflammation, the barrier is able to return to normal without further consequence. If a memory response occurs and, in particular, if T cells are recruited to attack what the body sees as potential invaders, a more long-term and recurrent pathway can be triggered. Horses tend to have a stronger inflammatory response in the eye than most species, making them more likely to suffer long-term consequences of inflammation.

So what causes this inflammation? There are a myriad of bacterial, viral, parasitic and even traumatic causes. Your veterinarian can help you sort them out, but every owner can look for the cardinal signs of inflammation in the eye: squinting, tearing, redness or even the more subtle change in iris color. The main focus of treatment revolves around controlling that inflammation and pain; but getting your veterinarian involved will help determine what drugs should be used. Often flunixin meglumine (Banamine) is given to decrease the inflammation and provide pain relief specifically through inhibition of that prostaglandin cascade mentioned earlier. Administered directly in the eye, atropine can be given for pain relief and to help dilate the eye as well as stabilize the blood–eye barrier and prevent ciliary muscle spasm, which itself causes pain. Topical anti-inflammatories, such as steroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), are often implemented, further stabilizing the barrier. But a veterinarian should be consulted because if you apply some of the medications to an eye that has a scratch on it or a corneal ulcer, for example, you not only will impair healing but could actually make the situation worse.

One event of uveitis does not necessarily mean the horse has or will get equine recurrent uveitis (ERU), also known as moon blindness. It is generally accepted that one event of uveitis does predispose a horse to developing recurrent uveitis, but if two years pass without another episode, the horse can be considered to have had an individual event.

Why does one event of uveitis make it more likely to have recurrent events? One reason is that each time you have this inflammatory event, you can end up with a small amount of scar tissue. This scar tissue is thicker than normal tissue, decreasing the ability of important substances like oxygen to diffuse across barriers to their intended structures. It also makes the fine adjustments in the eye necessary for accommodating light more difficult.

A second reason is the immune system itself. As mentioned above, the immune system is not supposed to encounter those proteins in the eye, and sometimes antibodies (attackers that are part of the immune system) start to target those proteins, often in the lens itself or the cornea (the transparent layer on the outside of the eye). The creators of these antibodies (B and T cells) may even form little nodules over time, like garrisons full of soldiers ready to fight if a foreign invader returns.

Another reason that has been suggested is that when uveitis occurs as a result of an infection, some of those infectious particles remain in the eye and are not cleared away. This is one of the reasons Leptospira (a bacteria) has been suggested as a cause of recurrent uveitis. Leptospira also has cross-reactivity with some tissues in the eye. Even if the bacteria have been cleared from the body, the immune system may continue its attack within the eye.

Within ERU, there are several classifications. The most common is classic ERU. In horses with this condition, you will be able to see obvious bouts of inflammation, but once addressed, there can be periods where the eye is normal or has minimal inflammation.

Insidious ERU more often affects Appaloosas and some draft breeds. Here there can be chronic low levels of inflammation that do not go away despite treatment. Another classification more common to warmbloods and European horses is posterior ERU, which could be either classic or insidious in its presentation, but the focus of attack is on the back of the eye instead of the front. This means that the retina and its blood supply, the choroid, are more often affected—the retina again being where the rods and cones (the structures that register light in the eye) are located. Some horses will be affected only in one eye, but it often occurs in both, with one eye tending to be more severely affected than the other.

When you buy a horse, the ophthalmic exam is quite important because some horses may have ERU but be in a stage of quiescence, where no obvious signs of active inflammation are present. Some signs a prospective buyer might notice include atrophy of the corpora nigra (those little bubble-like structures that sit on the inside rim of the pupil), odd coloring of the iris itself or any cloudiness in the eye. There are several other signs the average veterinarian might notice, but getting a board-certified ophthalmologist involved can ensure a clear diagnosis. Many of the signs may be subtle to an average practitioner but might be red flags to an ophthalmologist.

What can you do to decrease recurrence of uveitis? If an exact cause can be found, treating that cause will be central. However, there are some management techniques you can use to decrease the stimuli of inflammation. These include insect control and decreasing light exposure, both of which may be aided by the constant use of a fly mask in tolerant horses. Even changing stall bedding to a less-dusty alternative can be helpful. Use of large-flake shavings is a good option since they are often less dusty than finely ground sawdust. Eliminate any standing water or access to ponds where Leptospira and other pathogenic bacteria may live.

Also speak with your veterinarian about what vaccines currently being administered are absolutely necessary for your horse and consider a plan to spread out administration of those vaccines as far as possible. For many of the diseases we vaccinate against antibody titers can be measured and indicates how many antibodies have been produced against a certain organism. Unfortunately, this is often expensive and there are not many studies indicating how many antibodies are actually required to prevent disease. NSAIDs, such as phenylbutazone (bute) or Banamine, can be given 24 hours before vaccination and at the time of vaccination to decrease inflammation. This technique comes with the caveat that inflammation is what results in development of immune protection, and studies are lacking to say how many anti-inflammatories can be given and still have the body develop a good immune response. So where vaccination is concerned, it definitely requires weighing risks and benefits. Be sure to involve your veterinarian.

If your horse has recurrent uveitis, you can explore several surgical treatments. One is a suprachoroidal cyclosporine implant, which is placed in the tissue of the eye and slowly releases cyclosporine, a drug that specifically targets T cells and acts as an immunosuppressant. Not all horses are good candidates for this surgery, but careful patient selection can lead to excellent long-term control. Another surgical approach is a pars plana vitrectomy, where the content of the eye is sucked out along with inflammatory debris and replaced with fresh fluid. Antibiotics can also be injected directly into the eye to help fight infection. These two techniques are most likely to help horses who have tested positive for leptospirosis.

What is the overall prognosis for sight and performance with ERU? It’s poor. One study found that 20 percent of affected horses will go completely blind and that 36 percent will lose vision in one eye. Being an Appaloosa or testing positive to exposure to Leptospira increases the risk of blindness, according to Brian Gilger, DVM, MS, Dipl ACVO, and Anne Weight, DVM, MS, DACVO. That being said, many horses can still do their job with only one eye. For example, Santana, a Hanovarian stallion, made his Olympic debut in 2012 with his rider, Minna Telde, without his left eye. Also, Valiant, who was completely blind and ridden by Jeanette Sassoon, was able to compete through Prix St. Georges and even competed in a musical freestyle at the 2003 Festival of Champions at Gladstone. I should emphasize that these riders and horses were exceptionally dedicated and talented. Many blind horses adapt very well to a pasture life, especially if they have a buddy to hang out with, but that does not mean they will be competitive dressage horses. One-eyed horses, on the other hand, may adapt well and while they may spook more easily if something comes from their blind side and need a little different handling, they can become very successful competitive dressage horses.

If you’d like to explore uveitis in more detail, read Equine Ophthalmology, Elsevier, 2nd edition, by Brian Gilger, DVM, MS, Dipl ACVO, and Anne Weight, DVM, MS, DACVO.