Heather Sansom is the author of rider fitness ebooks Complete Core Workout for Rider, and a regular columnist in several equestrian publications including Dressage Today.?EquiFITT.com offers rider fitness clinics & workshops, Centered Riding? instruction, and convenient distance eCoaching for riders anywhere.? Subscribe to receive free monthly Equestrian Fittips, and download rider fitness eBooks at:??www.equifitt.com/resources.html

This article is about three key ideas: the link between suppleness and power, the way a horse and rider influence each other’s biomechanics, and what you need to get engaged hindquarters.

In last month’s Rider Fitness piece we discussed movement in your spine for absorbing the horse’s motion, and how this is related to correctly aligned and supple hips. Exercises suggested were for loosening common tight areas in hips. As a rider, you know that there is more to suppleness than flexibility. If suppleness were all about soft and flexible and nothing more, we would see more ‘floppy dolls’ in the show ring. Too much looseness may absorb motion effectively, but it can also cause undue wear and tear. Think about the tires on your car: if they are not properly installed, it will not take you many miles to completely wreck them as well as your wheel assembly.

An example of too much looseness could be the rider who seems disconnected in the middle: shoulders doing one thing, hips doing another, resulting in general problems with forwardness and straightness. The poor horse is hearing so much body-language ‘chatter’ that he can’t be very precise off the aids, because he can’t tell when a squeeze or other movement means what it is supposed to mean.

Suppleness implies tone. You could say ‘relaxed and ready strength’. For your horse to be supple, he has to be relaxed. For him to relax in what you are asking, he needs to have the physical ability, correct muscle memory, and mental comfort to do the exercise. He also needs clear leadership both physically and psychologically. For him to engage his body completely in correct movement, he cannot simultaneously also be fighting his own physique (or yours) to achieve the goal.

An example could be a horse who is going with an inverted back and hind end trailing, because his rider has gripped him in the mouth and is pulling backwards. This horse cannot relax into powerful movements with suspension. Instead, he will become tense as he attempts to reach under himself to move from the hind, fighting the biomechanics which are forcing his hind to trail. He will get a stiff back.

Examples of a rider fighting their own physique can include pictures such as the rider who has a tendency to rock forward in their seat, showing a stiff upper back and hollow lower back as they attempt to be straight in the saddle. Contrast this picture with a rider who is sitting correctly on their seat bones, and therefore does not have to exert force in their body to be upright in good posture.

A horse which is not quite fit and balanced for what you are asking. He will lose his suppleness when pushed beyond his ability, because he will not naturally have the strength and co-ordination for the movement. He will have to force himself, and this will compromise the movement.

Similarly, you have likely seen the relaxed and straight rider, who begins to stiffen up as soon as the horse gets fast enough. This rider, comfortable in sitting trot, became as stiff as a board when moving into lengthened or extended stride. This rider might have been straight, but passive. They did not have the correct self-carrying muscles engaged in a soft but ready availability for the gearshift to the bigger motion.

The rider’s seat area might not be correctly engaged, or have insufficient strength. Riders with insufficient strength will develop tension as an energy, and also as a physical condition of the ligaments and fascial tissue supporting their structure where the muscle tone is lacking.

Of course, the rider and horse affect each other. While it is the riders’ job to provide leadership in a positive way, we often see the horse’s motion or degree of tension influencing the rider, or the rider’s body influencing the horse in counterproductive ways.

Within her Centered Riding? framework, Sally Swift refers to the concept of comparable parts. The riders’ signals to their horse are so much more complex than a squeeze of a rein or leg, or shift of position or seat. For example, you can observe that flexion in the rider’s knee is related to the horse’s stifle. Bend and softness in the rider’s elbow is related to the horse’s knee. A rider who’s pelvis rocks forward with seatbones pointing to the cantle is often mirrored by a horse with a slight hollowing of the back and less engaged hindquarters.

Now that you know both the horse and rider need strength to get suppleness and softness, and that the horse will reflect the way the rider uses their body, we can discuss hind end engagement and how it relates to your fitness as a rider.

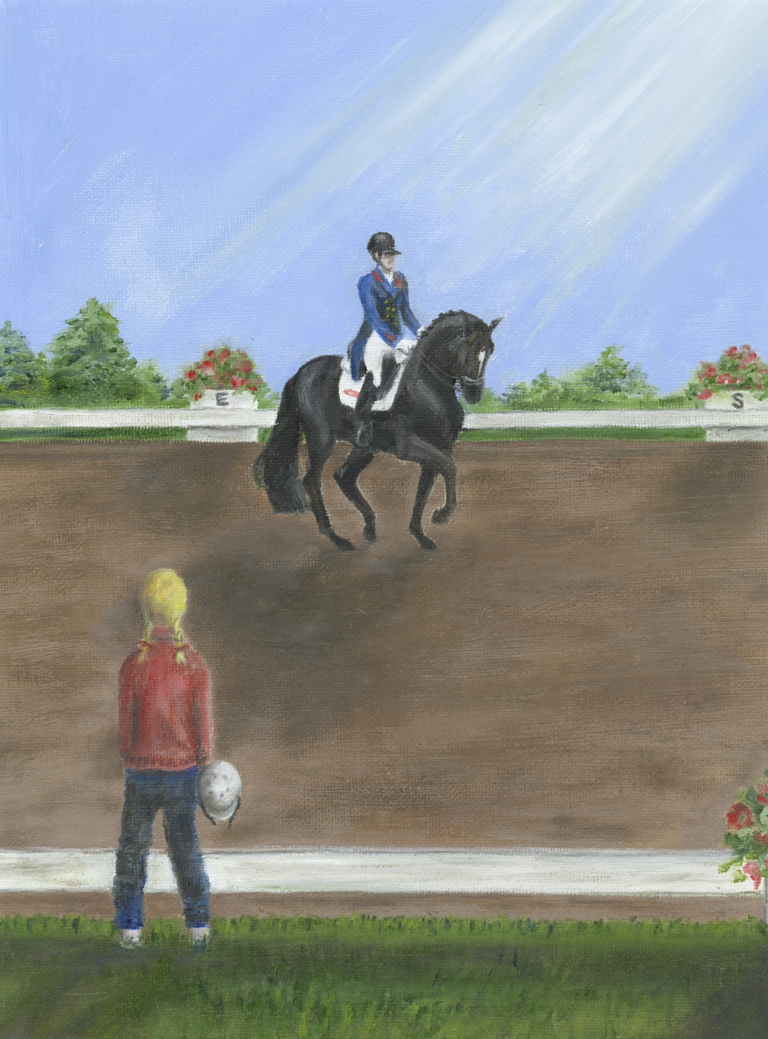

Let’s backtrack to suppleness. You want a soft and supple back. Because the back muscles lengthen when the pelvis rolls back during good hind end engagement, you know that softness and suppleness in the back happens when the horse can get his hindquarters under himself. Bringing the hindquarters down and propelling himself from hind feet planted well under his center of gravity, the back is raised in an uphill position. The major locomotive muscles for soft swinging backs, are gluteals and hamstrings in the horse. These are at the back of his haunch and leg. (See photo of Lori on Kestrel).

The Fjord horse in the photo does not have a conformation common in competitive dressage. It is trendy to focus on the horse’s front leg action only, and if you do so, you see rather shorter legs in this horse when compared to a bigger breed. You may also notice there is not so much lift compared to a horse doing what the old manuals called a ‘show trot’ without proper hind engagement. If you look at Kestrel’s overall frame and movement however, you can see that his legs are very parallel front to back. He is in a very pleasing trot with lots of energy, uphill balance, happy expression on a face at the vertical and engagement of his hindquarters. The rider looks fairly relaxed and straight.

The red arrows are pointing to his gluteals (at the top- rump) and hamstring muscles (behind on the leg). His ‘sitting’ or propulsive ability is directly related to his strength in and ability to engage these muscles. Mechanically, engagement also requires softness along his back so that his sacro-iliac joint can release enough to allow his haunch to drop. Notice also that he brings his hock well under himself, and that his pasterns are on a nice angle. His fetlocks are not being driven into the ground. The horse’s ‘seatbones’ are close to each other, and the top of his pelvis is wide (bones protruding near the loins- comparable to your hip bones just under your waist). He can place that leg directly underneath his body, and not out to the side of his body. The rider does not need to be kicking or worrying about nagging him with her calf, when his ears show he is already clearly listening to what she is telling him through her seat and hamstrings. She has more of an appearance of allowing him to go.

In horses, as well as humans, strong gluteals are the key to a good back (in daily life and any sport), and good hamstrings engaged correctly are the key to correct lower leg (in riders). If this horse could not use his hind end like he is doing, we might see his lack of engagement compensated for by too much cushioning and push happening through the fetlock. In the rider, lack of correct engagement of the seat and hamstring muscle for driving aids would show us flappy lower leg and a stiff back. In the horse, we would see stiff back, and the excess motion in the lower leg would be overload on the suspensory ligament with too much lowering of the fetlock.

By using the seat correctly, the rider can allow the horse forward, and signal a body arrangement which is more optimal for correct engagement in the horse. Squeezing the horse’s sides causes him to collect, or tense. Using the part of the hamstring under the seat and at the back of the thigh correctly, results in the thigh turning outwards slightly, which causes the calf to be applied as well.

Without correct use of the hamstring (and a listening horse), the rider would resort to squeezing, kicking, spurs or whip. You can use your hamstrings more effectively as a rider if 1. your body knows they are there, 2. you create muscle memory, 3. you have physical strength there. Using dryland exercises helps you reinforce a strong and correct connection with this muscle area, and also train more strength than is possible from the position of being seated in the saddle.

Since the part of the hamstring we are concerned about is up near the rider’s seatbone, machine type exercises do not seem effective. They tend to isolate the bulkier part of the muscle nearer the knee, which is not so useful for riding. Bodyweight exercises are much better. An exercise I like to use is the ‘hamstring roll-in’ using a fitness ball, because it also helps a rider work on symmetry and alignment at the same time as you are working on your hamstrings and gluteals.

For riders, it is preferable to do this exercise with your toes slightly pointed outward and seatbones coming closer together as they would be for riding.

Step 1: lie on your back with your legs on the ball, just under your calves

Step 2: lift your seat off the floor engaging your abdominals.

Step 3: bend your knees and roll the ball towards you as you lift your legs and hips higher into the air. Your goal is to get your feet standing on the ball.

The photos show a jumper client with her feet at a good angle for riders. The red arrows

show you where the gluteals and hamstrings are on the human athlete. You should work up to being able to do 20-30 at a time, a few times a week. If your lower back hurts, try flatting your back by tucking your tailbone more under yourself and making sure your abdominals are engaged in support of your back. If it still hurts, consult a physiotherapist or personal trainer on how to do the exercise correctly.

Call for topics: Over the past several months of Rider Fitness articles, we have covered many topics related to rider fitness. We would be interested in knowing more about the topics and issues you’d like to hear about. Please write to personaltraining@equifitt.com to suggest topics you’d like to see covered in future pieces.