Last October, the long-awaited New England Dressage Association’s Fall Symposium with Carl Hester began with a flurry of anticipation. It seemed that everyone from New England and beyond was there, and people were finding their seats at the Pineland Farms Equestrian Center in New Gloucester, Maine, two hours before the program was to begin to learn about Carl Hester’s training system. When the time finally came for his effusive introduction, Hester seemed humbled. “Thank you for this embarrassing welcome,” he said. “Who writes these things?” And, he added, “What you will see this weekend isn’t really my system anyway. Everyone’s system is somebody else’s system, and I’ve been fortunate to learn from so many great horsemen over many years. In time, you just learn to develop what works for you.” To that end, Hester offered the following advice.

1. Advice for Young Professionals

If you don’t have the ability to buy yourself a great horse or if you don’t have a sponsor to buy one, you have to buy what you can afford, even if it might be a 2-year-old. After I had achieved international success, I presumed I’d get other Grand Prix horses to ride. But no. So I bought what I could afford. That’s what you need to do. Then get a good trainer, which is a more important investment than what you put into a horse. Riders at the top always have several horses and they get inspiration and regular help every day. It can be a problem for those who keep their horses at home and do not have access to regular help. You have to get someone to help you on a daily basis.

2. Emphasis on Horsemanship

After the Olympic Games in London, I was asked if I thought our success was due to the fact that we turn our horses out. No! It’s the riding and training, it’s the horsemanship. We do, however, make sure our horses keep moving. It’s one thing to be a good rider, but it’s far more interesting to see what else a rider knows. The more you read and the more you can put other people’s practices into action, the more interesting and fulfilling your horse experience becomes. It’s important to learn about horse care, conditioning, biomechanics and more. When you become a true horseman, that makes your commitment serious. If you don’t have that, then training horses to any level has less meaning.

3. Focus on Rider Position

Straightness. We will always have the situation of a crooked rider on a crooked horse, and our goal is to make both straight. To that end, don’t look down to the inside. You’ll only find X there. Look through the middle, down your horse’s neck and through his ears. Or look up and out. The judges sit on the outside.

Hands. Often the rider’s right hand doesn’t match his left hand. It helps to look at your hands and see what they do. People have habits that are so ingrained that they feel normal, but you don’t have to become stuck in your ways. I have students who ask me, “Are my hands improving?” Even Charlotte [Dujardin] knows she can be hand-dominant and she works to improve that. You can always get better over a long period of time, so don’t take it personally if your trainer says the same thing every day.

If your outside shoulder is low, your inside elbow will come up. Fix it one way or the other.

Rider self-carriage. It is not only the horse that needs to be in self-carriage—the rider needs it, too. Many riders have their shoulders behind their seats, and I say to them, “If you were a horse, you would be hollow.” Sitting on a horse is more about standing.

Pay attention to your weight distribution in the upward transitions, too, and ride your young horse with a light seat. In the upward transition to canter, sit forward so your horse doesn’t have to lift you with his back. Your horse shouldn’t need to drop in the middle in order to get into canter. Bring your upper body forward and then canter. Then in the downward transitions, allow the horse to stay forward with the head and neck and ride the transition from back to front. Close the horse from behind.

Some riders push with the seat in the canter transition, which makes them heavy on the horse’s back. If it’s your nature to push and shove, concentrate on getting lighter in the canter transition. In general, when you ask your horse to go forward, bring your upper body forward. When you come back, bring your upper body back.

In the name of sitting up straight, don’t exaggerate and end up making your back hollow. Your upper body has to stretch up through your head and your lower body should stretch down to your feet.

Riding can be tiring, so go to rising trot whenever you need to catch your breath. You can even do shoulder-in and other collected exercises rising. You can go from rising to sitting until your horse relaxes. Rising in passage is an incredible way to get more expression and lift.

4. Priorities for 4-Year-Olds

First things first. Make sure you’re safe. To be a good rider on young horses you need balance, nerves and you have to be quiet with sensitive aids. Look for rhythm and good contact. Use repetition to teach your 4-year-old.

When you first take a young horse away from home, go to a symposium or a clinic instead of a competition. It’s usually a better experience because you can focus on relaxation there.

Take time. The dressage horse won’t generally mature until he’s 7, so go slow with 4-year-olds. At my yard, they generally work 20–30 minutes maximum, four days a week: Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday. They have Wednesdays off and they hack in the field on the weekends. If you’re a one-horse owner of a 4-year-old, it’s tempting to go too fast. Sometimes the young horse just needs a break for a few weeks because he gets tired and muscle sore. With a hot, tense young horse, try not to ride too long or too hard.

Balance. Self-carriage begins with the young horse. He has to carry his own head and neck in the stretch. The 4-year-old will change from a downhill balance to a horizontal balance before finding an uphill balance. When the horse understands going from the leg and sitting up a little when the rider uses the rein, then both horse and rider start to understand a half halt.

The whip. Be sure the horse is in front of the leg and not going forward only because you have a whip. The whip is an aid that needs to be used as help for the horse in the right rhythm. Don’t just whack him with it without timing.

5. The Value of Basics

The 20-meter circle. On the 20-meter circle, do transitions. How many transitions in a schooling session? Countless. The future is based on these transition exercises that develop obedience, suppleness and engagement. Horses always need to become more supple in one direction or the other and the circle helps. What else does the horse learn on 20-meter circles? They learn to turn from the outside aids. They learn to do their transitions from back to front.

Contact. Some horses have the tendency to be strong in the hand or light in the hand. You don’t want to carry your horse’s head around. On the other hand, you must be able to tell the difference between lightness and being behind the bit, which is more difficult to correct. The horse must be forward to the hand, and then lightness comes from the contact. There’s a moment when you can use your leg and a moment when you cannot. The moment you can is when he’s going to the bit.

Stretching. This is a major part of the work at every level. Young horses find their balance in the stretch and they demonstrate basic self-carriage. It’s important that riders not pull the horse’s head down or hold it down.

Relaxation. You can’t make a horse relax. You have to help him relax. When you work on a circle and do suppling exercises, it helps. The horse needs you to help him unlock himself so he can relax.

Maximizing and improving the walk. Uthopia had a walk that was small, which cost me many points, so I learned to maximize the overtrack in walk. Push your horse’s head away from his body to make him longer through the topline. The result is that there is more room to overtrack [with the hind legs stepping beyond the fore prints]. Get as big an extension as possible. The walk also improves after the trot and canter.

When horses have a huge overtrack, they can have issues with collecting it. Get him to walk here and there on a long rein. Then zig-zagging across hills can strengthen and improve the walk and make the horse more mobile.

6. The Progression from Young Horse to Grand Prix

The double bridle. If your horse doesn’t take the rein in a snaffle as a 7-year-old, he’s not going to take the double. To introduce the double bridle, you can use it while hacking, but make sure you don’t use it for cheating. Your horse has to be in self-carriage in the double bridle for it to be effective.

Straightness. As horses get stronger, you need to see that the horse’s hind leg is placed in the right way. How does he “step in the right way” from behind? Think of the width of the horse’s hindquarters and the width of the forehand. The hindquarters are wider. In order to balance, you must ride your horse’s inside hind leg in a position between the front legs. To avoid the common problem of losing straightness by overusing the inside rein to turn, learn to turn your horse with your outside aids.

Transitions. Wherever I go in the world, I will always be helping riders do transitions with an uphill tendency. It’s extremely difficult and there aren’t many in the world who can make it look easy. Activate the hind leg in all downward transitions and when you use your leg, be sure your horse reacts behind and not in front. Then take and release to open the neck forward. If you hold the half halt too long, it won’t work.

In trot–canter–trot transitions on the circle, horses come into a balanced “swing speed.” You can’t manufacture that connection. You get it from transitions and the horse starts to “take you,” then he can be positioned and straightened.

In walk–canter–walk transitions the horse learns to sit, put more weight on the hind leg and lighten the forehand. Ask him to sit with small steps and then when the moment is right, give the reins and ask for the transition. Keep practicing and this will make him strong. The horse will learn to add weight to the hind leg when you sit.

In every transition you do, give it your best shot. It’s discipline, which is what dressage is really about. And remember to ride the inside hind between the front legs before and during all transitions.

Half-transitions. When you have a small mover, you have to teach him to get bigger. When you have a big mover you have to teach him to get smaller. If you have a big mover, do half transitions. For example, from a trot, almost walk and then trot again. These transitions give the horse the smaller trot that he needs so he can bring his hind legs under. Then from the smaller trot, the upward transition back to trot or to a canter depart will be better engaged, or carrying more weight behind.

Self-carriage. The meaning of self-carriage is having the horse on his own four legs. We work on it from the beginning, but it takes years to actually achieve.

7. Ideal Qualities in a Horse

Temperament is very high on the list of factors to consider when purchasing a horse. You also need a very good walk, trot and canter and good enough movement. Correct training can improve the trot, but the walk and canter need to be as good as possible because they are both difficult to improve. Make sure the walk rhythm is correct and remember that the Grand Prix has a large percentage of canter work.

8. The Competition Arena: Take Risks and Be Positive

When you try not to make a mistake, you aren’t taking a risk. You need to take the risk and learn to make fewer and fewer mistakes. If you’re getting 68–69 percent, you have to take more risks. Seventy percent is, after all, only an average of 7—“fairly good.”

When you take your performance into the ring, be sure to think about positive things. For example, I might advise someone, “Think about rhythm.” That’s all—and it’s positive.

Movements & Exercises

Every movement has a start, a middle and a finish. Ride them all.

Shoulder-in. How important is the shoulder-in? It’s one of the most useful exercises. It engages the inside hind leg, it gets your horse straight and is the best preparation before travers, half pass and pirouettes. We could say that it’s done primarily with the inside leg and outside rein, but I think it’s done with both legs and both reins. If you don’t use the outside leg, you might have an empty inside rein and the haunches might go out.

Half pass. Shoulder-in and travers are prerequisites to half pass. To develop half pass, do travers until you have a good-quality bend, and then it’s easy to half pass.

Flying changes. The aids for a flying change are often specific to the individual horse and rider. It depends on the length of the rider’s leg and the conformation of the horse. Don’t stop your horse and correct him when he has made a mistake in the changes. Correcting the underlying problem will correct the change. Often the canter needs to be improved. To that end, you might need to get off your horse’s back and gallop him or do transitions between medium canter and collected canter. After the medium, add the medium energy into the collection. The improved canter should improve the flying changes.

As for the timing, ask for the change when the horse is coming down in his stride because then he will do the change when he comes up. Put your rhythm into his rhythm.

Pirouette. You can’t make a small pirouette from a big canter. Bring your horse back as if I could walk beside him. The ingredients of a pirouette include: collection, the ability to go forward and the ability to go sideways with bend. Your horse must be able to carry himself straight on the centerline. You must have control with enough collection in and out.

Exercise 1. To Improve Balance in the Corners

This exercise will enable you to ride the corner instead of being just a passenger and you’ll find that your horse will be able to fit two more strides in the corner than usual.

Step 1. Trot to the corner then halt and stand in the corner.

Step 2. Turn 180 degrees to the outside and trot out.

Step 3. Repeat and from the next halt, turn 180 degrees to the inside and trot out. Soon your horse will start to wait and ask what you want.

Step 4. Next, trot through the corner and see if he waits for you.

Exercise 2. Improve Pirouettes

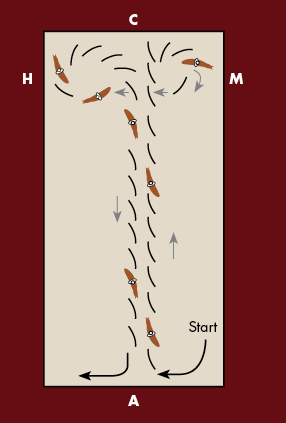

Turn down centerline at A and do travers right (see illustration at right). At C, track right to M and do a very large 3/4 pirouette in the corner at M. Ride the M–H line in travers and then do a very large 3/4 pirouette right in the other corner at H. Then go back down the centerline in travers right. Track right and do half pass on the diagonal. Then repeat to the left.

Exercise 3. The Driving Rein

To improve the connection and prevent the rider from breaking in the wrist, try using a driving rein with the thumb on top and the fingers below. This gives a totally different feel, but it is easier to get the horse to reach his neck forward. It feels a bit weird, but it works. Keep your hands in front of you.

Exercise 4. Honesty in the Shoulder-in

To prevent the rider from doing too much with the hand and to put the horse more on the other aids, try this: From the shoulder-in on the track, bring it slightly off the track and then ride straight in shoulder-in parallel to the long side.

Exercise 5. To Help the Rider

Sit to the Inside. Many riders inadvertently sit to the outside in lateral movements thereby blocking the outside hind leg from coming through. The rider can lean extremely to the inside until she can see the inside hind leg. Then she will start feeling the importance of the weight aid.

Exercise 6. Honesty in the Leg Yield

Horses often are just falling in in the leg yield. To be sure your horse is actually leg yielding, try this: Do two steps of leg yield and then go straight. Repeat. Keep your horse’s head in front of his chest.

Leg yield in canter is not a movement in a test, but it makes the canter freer without your horse needing to collect as he does in half pass.

Troubleshooting

- If a horse is difficult because he’s stiff, he’s not trying to annoy you. He is stiff. He needs your help in working through it, and he needs time.

- Tilting in the bridle occurs when the horse isn’t properly in the outside rein. Do shoulder-in with no flexion until the horse becomes even in the reins. Then you can start to ride with inside flexion. When you ride shoulder-in to renvers, the outside rein becomes the inside rein, so ride shoulder-in as if you could ride renvers at any moment.

- How does one develop a trot lengthening if the horse doesn’t have big strides? The classical way is to know that good collection is what makes good extension. Then you have something to release. That’s for someone who has correct collection. If not, try to treat it like a race and let your horse learn on a circle and see what he can do. Do transitions to help him.

Carl Hester is a five-time Olympian and a true horseman. In addition to his own position on the 2016 British Olympic team aboard Nip Tuck, he was also the trainer of all the other British riders who clinched the team silver medal in Rio. Hester has Olympic, World and European Championship gold, silver and bronze medals to his credit. Most recently, he won the individual bronze medal at the 2017 World Cup in Omaha. In 2013, Queen Elizabeth awarded Hester an MBE: a member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

This article first appeared in the January 2018 issue of Dressage Today.