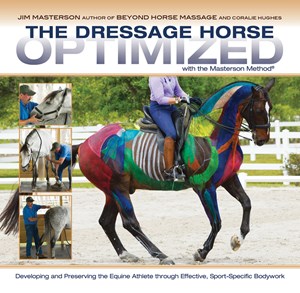

Masterson Method Bodywork is designed to meet the needs of the equine athlete. Body suppleness and the forward reach of the legs—medially (toward the middle of the body) and laterally (outward)—are compromised when range of motion of the skeleton is restricted. Range of motion of the joints becomes restricted when muscles become tight and lose their natural ability to contract fully and relax fully. When a joint is restricted by excessive muscle tension too long, permanent damage can occur to the joint.

In general, tension develops in the muscles over time merely due to the effort it takes to do the work our horses do for us. Additionally, learning a new skill or movement calls for developing new states of balance, new motion coordination and strength in new muscle complexes. This further challenges the musculoskeletal system and can build tension in the muscles.

When tension builds unevenly in the body, torque can be put on the skeleton, which further limits the horse’s flexibility. Unnatural tension in the muscles puts unnatural levels of tension on the tendons that connect muscle to bone. Tendon injury is one of the most common career-limiting soft-tissue injuries. The principles and techniques employed in the Masterson Method focus on releasing tension from the muscles and soft tissue and restoring range of motion to the joints. These techniques can go a long way toward maintaining or restoring suppleness and flexibility in the body and reach of the legs.

Finding and Releasing Tension

When feeling threatened by something in the environment, the horse is hardwired to run away first and ask questions later. For millennia, his survival has been dependent on life in the protection of the herd. Consequently, horses try not to show discomfort in their bodies. They hide it until lameness or sickness develops that they can no longer conceal. This is especially true in what we commonly refer to as stoic horses: It isn’t that stoic horses don’t feel the discomfort. Indeed, they may be more sensitive than average. They just try harder not to show the pain or weakness. To show weakness means to likely be cast out of the herd. The predators are alert, always looking for a sign of weakness they can attack. This tendency to hide discomfort can complicate diagnosis of performance issues.

Bracing and Body Language

With the Masterson Method you discover areas of discomfort or tightness in the horse by observing subtle changes in the horse’s body language (often merely the blink of his eyes) during the bodywork. As you are running your hand lightly over the body or moving a part of the body, such as the leg or neck, through a range of motion while it’s in a relaxed state and you observe the horse blink, it means that the horse’s body is telling you there is something there that the horse needs help with.

Obviously, if you use more pressure you might elicit bigger reactions such as flinching or pulling away, in an area where the horse is extremely sore. But by learning to observe subtler changes in the horse’s behavior, you can determine both where there is discomfort from tension and when the horse has released it. Neurologically, he can’t stop his eye from blinking when you get near an area of special discomfort if you are using a level of pressure that he can’t brace against. With experience, you learn to recognize the blink from pain as different from the blink from a fly or other natural reasons. Even a stoic horse can’t avoid releasing his tension secrets to a watchful observer. By applying similar techniques that follow subtle changes in body language and staying under the horse’s bracing response, you can get him to release deep-seated tension on his own.

Staying Under the Radar

If you have hurt your arm and you go to the doctor, you are going to naturally tense against his manipulation of your arm as he examines it. If a nurse gives you a shot, you have to fight against the natural reaction to tense against the insertion of the needle, even though you know that it will hurt more if you tighten the muscle. So it is with the horse. In this case, staying under the radar means that the techniques of the Masterson Method are performed in such a way that the horse can’t brace against them. This requires feel and skill that take some time and practice to develop, but if you begin with the basics, you can get results immediately.

Naturally, horses are most likely to brace against a technique when it involves an area of discomfort. For example, every horse owner knows how touchy a horse can be about the poll. This is an instinctive protective reaction due to the typically high level of uncomfortable tension that is in the region of the poll. In the performance of any Masterson Method technique, you must feel when the horse is about to brace or pull back and soften, before the bracing response happens. This is the principle of nonresistance.

The Principle of Nonresistance

The Masterson Method comprises two basic categories of techniques:

1. Those that release tension in situ (without movement) (see Photo A).

2. Those that release tension through range of motion while in a relaxed state (see Photo B).

Releasing tension in the muscles and restoring flexibility and range of motion to the skeleton both work together. By simply relieving tension in the major muscles that control a joint you allow the joint to operate more freely. Asking for movement of a limb or body part while it’s in a relaxed state can release even more tension in the muscles and soft tissue that control that area of the body. The manipulations that release this muscle tension give the feel that they grease the joint, further freeing the joint itself.

Some experts say the natural operation of the body’s hyaluronic-acid pump in the cells of the tissue lining the inside of the joint requires normal range of motion of the joint in order to work properly. The natural hyaluronic pump removes old lubricant and secretes fresh. Since hyaluronic acid is a major lubricator of joints, maintaining range of motion of the joints can help preserve the body’s natural skeletal- and cartilage-protective systems.

Whether you are using a technique to release tension in situ or to restore range of motion, how you ask the horse is fundamental to the success of these techniques. If you ask by using too much pressure or moving too fast, the horse will brace—either externally or internally—against the technique. If the horse is not in a relaxed state when you ask for movement of a limb there is likely to be bracing against the movement and tension is generated.

“Ask” is the key word here. We invite the horse to release tension. We can’t make him relax a muscle. We invite him to move a limb using a technique that will ultimately release tension. We never demand the movement. The use of force or thrust could potentially cause damage and is strictly reserved for trained veterinary chiropractors.

Until he’s experienced the method, the horse doesn’t know he will feel better soon. He only knows he is tight and uncomfortable now and he doesn’t want to have you invading that protected spot. He wants to guard the area and not let a possible predator know there is an area of weakness. And certainly, man is the ultimate predator. We have hands that grasp and are easily hard and our movements are typically fast. The horse can feel when your hand near his body is hard and stiff or soft and relaxed. And it matters in the bodywork.

This doesn’t mean we don’t use pressure with this method. We do use pressure with some techniques, but the key is to yield when the horse yields and soften when the horse softens, for the horse releases tension when we are under his bracing response.

For example, when you ask the horse to bend his nose toward you, and he resists because the muscles of the poll and neck are tight, your first impulse is to pull harder to make him bend toward you. If you react to the resistance by countering it, the horse will continue to resist, tense or brace. He may still be bringing his head toward you, but he is still, to some degree, resisting, tensing or bracing as he’s moving. You cannot force a horse to relax. Only the horse can relax himself. It is counterproductive to get into a wrestling match with a 1,200-pound animal with enormous strength. The horse has to let us help him.

The principle of nonresistance in the Masterson Method Bodywork teaches that when the horse resists, soften your hand(s) slightly (see Photos 1A and 1B). When the horse feels you stop pulling, he will stop pulling and you can continue the movement. When you give the horse nothing to resist, he will stop resisting and you can immediately continue on with your move. You must train yourself to feel the horse brace and immediately soften, which means stop asking for the technique, wait until you feel him relax, then continue on with the “ask” for the movement.

Getting the Horse to Yield to You In a Relaxed State

1. When you ask for any movement, start with the slightest amount of pressure, gradually increasing the amount with each “ask” (see Photo 2A).

2. When you sense the horse yielding the slightest bit (even thinking of shifting his weight, for example), yield immediately, then ask again right away (see Photo 2B).

3. Repeat asking by using this process until the horse is yielding to you with almost no pressure from you or resistance from him (see Photo 2C).

If the horse resists, you can gradually increase the pressure when first asking, but you must soften or yield the instant you feel any yielding from him. Remember, start with the softest feel possible and yield at the very first sign of the horse yielding. Often, the harder you push, the harder the horse pushes back, which is the principle of nonresistance in reverse. Timing is key here. Many of you riders will recognize that you might already use this principle when riding.

If there is an injury or excessive pain in an area, causing the horse to resist doing any techniques that ask for movement, he will continue to resist in order to protect the area. In any case, whenever you meet resistance, soften. In this way, you run little risk of aggravating a hidden injury.

Relaxed State vs. Active State

Under the pressure of training when being ridden, the horse, in his effort to please, can show reasonable length of stride or range of motion of the legs. On the other hand, we can take the same horse and ask for range of motion of the legs (in a relaxed state) from the ground and find that it is actually difficult for him to release the limb forward, backward or to the side. This is a horse who could be overpowering his muscle tension under the demand of the work and his eagerness to please and he is straining against himself in his training sessions. Moving the limb, muscle or joint through a range of motion while it’s in a relaxed state during bodywork releases the tension and restriction in the muscle and connective tissue of the joint. More important than the amount of movement is the amount of relaxation. The relaxation in the movement is what releases tension in the tissue.

Levels of Pressure

There are five levels of pressure in the Masterson Method (starting with the lightest):

1. Air Gap: You are not laying your hand on the horse. There is literally a gap of air between the horse and your hand. The gap can range from touching the ends of the hairs to many inches away from the body. Often, highly stressed horses or areas of particular discomfort (for example, the poll) can best be first approached using the air gap in order to stay under the bracing reflex of the horse. When some tension has released, then the horse may be able to tolerate the next level of pressure.

2. Egg Yolk: This is the amount of pressure it takes to barely indent a raw egg yolk with your fingertip.

3. Grape: The amount of pressure it takes to indent a grape.

4. Soft Lemon: The amount of pressure it would take to squeeze a soft lemon.

5.Hard Lime: The amount of pressure it would take to squeeze a hard, unripe lime. In some cases this can be just about as hard as you can push.

You will have to become accustomed to just how light the pressure usually is when the technique entails touching the horse’s body. It is a human notion that really getting into the muscles yields a better response. The horse has exquisite neurology and is exceedingly sensitive to very light touch. Softer, lighter and slower almost always yield the best results because the horse’s bracing reflex is not triggered.

When you first start doing bodywork, it is easy to misjudge how much pressure you are actually using because you are focusing on hand and body position and the details of how to do a technique. However, the level of touch you use is the single most important thing that will determine the level of success you will have. If you use too much pressure, the horse will either brace against you or block it out. In either case, there is no release of tension. When in doubt, the cardinal rule is: Go slower. Go softer.

The way you learn how the levels of pressure and the responses work is through Search, Response, Stay, Release (SRSR):

Search. With a soft hand in air-gap or egg-yolk pressure, slowly move along a line just off the topline of the horse’s neck (see Photo 3A).

Response. As you go slowly along the neck, watch the horse’s eye for a blink (see Photo 3B). This tells you your hand is likely over an area of tension. If you aren’t sure the horse blinked because of your action, simply run your hand very slowly and lightly across the same area again. He will blink again if it was due to tension in the area and if you haven’t moved too fast or too heavily. Remember, the horse can feel if you are using a soft, relaxed hand or a stiff, hard hand. The horse will not respond to a hard hand even if it is in air gap.

Stay. Don’t move your hand from the spot. Maintain no more than the same level of pressure you started with, or lighter, and stay (see Photos 3C and 3D).

Release. Eventually, the horse will release tension in the area you have drawn his attention to with your hand (see Photo 3E). When he does, you will see one of the release responses, often a lick and chew.

Working by Sections of the Body

Dressage horses commonly carry extra tension in the poll, behind the jaw, over the topline of the neck, in the pectoral muscles, the back, the shoulders, the lumbar and psoas muscles and the driving muscles (gluteus medius, biceps femoris and other hamstrings and the groin muscles). The limbs need extra mobility laterally, medially (inward) and forward. The thoracic sling must be free to lift. The back needs maximum flexibility longitudinally (to round and lift) and laterally (to bend). The dressage horse also needs to be able to flex the neck laterally at the poll to both sides.

You will notice that many of the techniques used in the Masterson Method will release tension in muscles directly related to specific dressage movements by following the same movement of the area as it is performed under saddle, but during the release technique, the movement is done while the muscles are in a relaxed state.

Essentially, tension is relieved with the horse in nearly the same body positions as he is in the work that caused the tension to begin (see photos above). The Masterson Method is especially effective for dressage horses and easy for the therapist.

When tension accumulates in one area of the body, it also affects movement in other areas. For example, when tension is released in muscles surrounding the scapula by using Scapula Release Techniques, it releases tension in muscles that affect movement in the hind end, such as the longissimus dorsi muscle that attaches at one end to the vertebrae of the lower neck directly in front of the scapula, runs along each side of the back and attaches on the other end at the pelvis. So, you can see that releasing tension in this muscle affects flexibility in the scapula, the back and the hind end.

The Horse is the Guide

Because the Masterson Method is built on the principle of nonresistance and follows the body language signals of the horse, the horse is the guide. The horse tells us everything: where to work, the level of pressure to use, which techniques to use and in what order.

Remember, the horse is like an onion: It takes time to peel away layers of stress. He can participate only so long in a single bodywork session without getting overwhelmed. Very deep or longstanding issues can take multiple sessions to release. It is important not to try to fix everything in one session. Doing regular bodywork on your horse will help you be more in tune to him as a being and your relationship with your horse will be strengthened—an excellent side benefit.

Don’t miss the handy Masterson Method pull-out chart between pages 48 and 49.

Responses that Demonstrate Tension and Release

The horse communicates with others of his kind as well as with you through body language that is often quite subtle. The responses you look for are changes in behavior that correlate to something you are doing with your hands in the bodywork. It takes time to learn to differentiate random behaviors or behaviors caused by something other than actual responses to the bodywork. When you aren’t sure the behavior is in response to something you are doing in bodywork, just repeat what you did and see if you get the same response. If you are using light enough pressure, the response is almost always repeatable, especially eye-blinking, which the horse can’t really guard against. However, if you are using too much pressure or moving too fast, the horse will block out the second try.

There are two categories of responses you are looking for: 1) those that indicate where the tension or discomfort is and 2) those that indicate small or large releases of tension.

Responses telling you where the tension is. Often, you know immediately where there may be tension because the horse’s body feels abnormally hard in specific areas, such as the neck or back. The horse can also tell you where tension or discomfort has accumulated in soft tissue:

• by blinking his eye when you approach the affected area with your hand or fingers (when you use almost no pressure).

• by flinching when you touch an area using hard pressure—sometimes an area that you didn’t yet know was uncomfortable.

• by actually moving away from pressure.

• by threatening to bite or kick in extreme cases of discomfort or concern.

You can also feel the tightness and restriction in movement when doing a technique that calls for the movement of a limb or body part. These are natural reactions to pain, and the horse isn’t being bad. To help your horse, you have to learn to manage these reactions and other evasions to the techniques while still maintaining the principle of nonresistance.

Responses telling you when tension has released. Body-language responses to your bodywork that indicate the horse is releasing tension can range from the subtlest response, such as:

• the eye softening or blinking

• a change of breathing—usually slower and deeper but sometimes faster

• twitching of lips, eyes or nostrils, which means the nervous system is processing the release

• lowering the head and neck

• drooping lower lip

• sighing

• passing gas—especially when you are working on the back end

• staring into space or zoning out.

And then there are bigger responses that indicate large, deep releases of tension such as:

• repeated yawning (see photo below)

• rolling back the third eyelid

• snorting and sneezing

• nose running—from sinuses that are draining after release of tension in the poll.

There are other consistent behaviors or responses that, if they correlate to what you are doing, indicate that the horse has released tension:

• shifting weight from leg to leg

• dropping one hip, then the other

• licking and chewing

• reaching around to scratch his flank or hip-flexing/stretching the trunk

• head-shaking—feeling sensation in the poll (see photo below)

• whole-body shaking

• stretching

• fidgeting.

You will need to step back from the horse frequently to give him room to feel the release, and to see what he has to say. Horses vary in how comfortable they are releasing in public. Give him plenty of space and time for the body to feel what is going on. Step back after every technique. It’s a good habit to get into.