As riders, we want the horse to be soft and supple in the mouth. As an equine dental practitioner, I can tell you the horse is only capable of giving this feeling when the jaw can move freely front to back and side to side. When you first learned to ride, you were told that the horse follows the nose. That is a simplified explanation. The horse actually follows his jaw in the bend or the turn. If you pick up the right rein and ask for bend on the right side, the horse’s jaw has to be able to follow the bit and then the horse’s nose turns along with the poll and the whole spine. Additionally, when we ask the horse to go into a frame and be through, the horse’s jaw has to slide forward, which we call the anterior movement of the mandible. When the nose comes up, the jaw moves back. The jaw moves left and right as well as forward and backward, and, therefore, the jaw’s flexibility is directly related to the horse’s ability to come through the neck and the topline. How do we achieve that flexibility?

Finding the Right Dentist

Equine dentists come in all shapes and sizes. However, there are several organizations that educate, certify and promote equine dentists. I encourage riders and trainers to find an equine dentist certified in one of these programs because the quality of work is probably going to be that much better than your average dentist with two floats and a bucket and no formal education. Certified practitioners tend to be educated in anatomy and physiology of the horse and have proven their ability to actually perform dentistry on a live animal in a controlled testing situation.

Questions you can ask your current dentist or a new dentist you plan to use, include:

• Are you a member of any equine dental association? Are you certified?

• Did you attend an equine dental school? (There are three in the U.S.)

• Do you use a full-mouth speculum?

• Do you use motorized instruments?

Today’s standards of dentistry are light years away from what they were 20 years ago. It all has to do with the quality of instrumentation that has been invented or reinvented over the years. There is still a place for the nonmotorized instruments, but a full-mouth speculum and motorized instruments are considered standard. However, the debate about motorized dentistry is still raging. One owner said to me that she is afraid of motorized equipment because she had heard you can do so much damage to horses’ teeth in so little time. Yes, you can, but you can also do so much good in such little time. Any equipment may be used properly in an educated person’s hands but can be dangerous when used improperly. Dental schools are thriving around the country and they promote state-of-the-art education and instrumentation and teach students how to properly use the equipment. With this information, a certified dentist can float the horse to allow freedom of movement in the jaw.

The Balanced Mouth

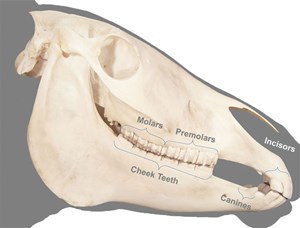

Most importantly, the horse’s mouth has to be balanced. When the horse is floated, the dentist removes all hooks, ramps and/or excessive ridges on the molars’ surface because these lesions contribute to the locking of the jaw. In addition to floating the sharp points, the dentist balances the mouth, which means he makes all the teeth at the same crown height. In other words, if you were to look at or feel the horse’s molar battery, where the molars are located, the teeth are all the same height and aligned at the proper angle. The molars that are the same height front to back allow the horse’s jaw to slide front to back and left to right more easily. If the jaw is unable to slide easily, the horse is forced to open his mouth when he wants to slide the jaw. This can contribute to connection issues while riding, such as bracing, opening the mouth and tongue problems.

Besides addressing the molars, the dentist balances the mouth by addressing the incisors, which are the teeth located in the front of the mouth. Grazing on low-quality forage wears a horse’s incisors in the wild, but eating hay in a stall often requires a dentist to float them. The dentist adjusts the incisors to the proper angle, which is measured viewing the jaw from the side. Five to 10 degrees is generally accepted, but the less steep this incisor angle is, the more easily the jaw can slide front to back comfortably. Ideally, the exact angle of the incisors should be parallel to the horse’s temporomandibular joint, or TMJ. If the angle of the incisors is steeper than the ideal, it catches the jaw as the horse flexes, and when he’s round it causes the mouth to open since the jaw cannot slide forward properly.

When the teeth come out of contact with one another to overcome an unbalanced mouth, the constant action puts unnecessary stress on the horse’s TMJ. That pain can cause additional connection issues.

When it comes to freedom of movement in the jaw, an overly tightened flash noseband or cavesson is counterproductive to what riders want to achieve in their connection and for the performance of the horse. This is due to the fact that the tight pressure around the nose constricts the movement of the jaw front to back and left to right. If the jaw is constricted in movement and the horse is unable to open his mouth at all, what anatomically happens is the horse then braces his body to turn the head when the jaw can’t fluidly move. For example, the added burden of a super-tight noseband works against throughness because it doesn’t allow the horse to drop his nose and be round due to the jaw not sliding comfortably forward.

Throughness, Soundness And Dentistry

If the horse’s jaw can move freely, then the rest of the body can, in theory, move freely. Only if the horse is comfortable can he flex his jaw and become round and come through, therefore traveling in the most correct way possible. This is what will protect his soundness. If the horse cannot comfortably slide the jaw forward, back, left and right, he is not going to be comfortable in that position and, therefore, not be comfortable coming through the back. If he is hollow because he is protesting the difficulty of the roundness, he is upside down and likely stabbing his feet into the ground. The horse’s joints are not made to take that concussion. When the horse is trapped upside down for a long period of time, you will begin to see joint problems. Of course, many different factors are involved, but in my opinion, if the horse’s dentist is working for him, you will likely see fewer problems not only in the jaw, TMJ and poll, but in all joints.