When you think skeletal disorders and spinal issues, you certainly don’t think “four-star event horse.” Yet Meg Kepferle’s off-the-track Thoroughbred gelding Anakin is just that: a four-star eventer with kissing spines, a scary-sounding condition where bony parts of the horse’s spine touch or even overlap. Like Anakin, many horses with kissing spines can have full performance careers. But it’s a complex disorder, and proper treatment and management are key to keeping these horses comfortable and going strong.

Here, Kepferle—a former groom for top eventer Sinead Halpin who now bases her own training operation at Mountain View Farm in Long Valley, New Jersey—shares Anakin’s story. And Weston Davis, DVM, DACVS, of Palm Beach Equine Clinic in Wellington, Florida, provides an expert perspective on the disorder, its causes, treatment and outcomes.

What are Kissing Spines?

0010.jpg)

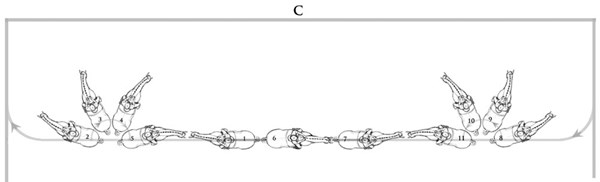

In technical terms, kissing spines are known as interfering or impinging dorsal spinous processes. The dorsal spinous process is the bony part sticking up from each vertebra. Ideally, the spinous processes are evenly spaced, allowing the horse to comfortably flex and extend his back through a range of anatomic positions. But with kissing spines, two or more of these bony extensions get too close, touching or even overlapping in places.

This can lead to restrictions in mobility as well as discomfort, which ultimately can lead to back soreness and performance problems. In fact, kissing spines are one of the leading causes of equine back pain. And over the long-term, they can contribute to additional issues, such as bone cysts or sclerosis, the thickening of bone or new bony deposits at the margins of the dorsal spinous process.

Kissing spines can theoretically happen anywhere in the thoracic or lumbar region of the back—the regions of the spine with a prominent dorsal spinous process, says Dr. Davis. But, he adds, almost all cases will occur in the region from the down-slope of the withers through the thoracic region—from around vertebra T6 through T18. This is the part of the back where your saddle typically rests. Kissing spines is uncommon over the lumbar region, or lower back.

Not every horse who exhibits kissing spines on radiographs shows signs of discomfort. In many horses, says Dr. Davis, kissing spines are found incidentally—for instance, when a buyer requests back X-rays during a pre-purchase exam—not because a horse exhibits symptoms. In those cases, he adds, “It becomes a challenge to know if it will ever become a problem later for that horse.”

Early on, Anakin showed signs of back tightness. “He was really tight in his back. You could see the spasm,” Kepferle said. “The muscles looked and felt tight, almost contracted. Your horse’s muscles should have some elasticity to them when you feel them.” For horses like Anakin who do have symptoms, why the pain occurs is actually “a super tricky question,” says Dr. Davis. “There is not a concrete explanation for where the pain comes from or why some horses are fully asymptomatic with horrible X-rays while others with relatively minor impingement can be extremely painful.”

He surmises that it’s most likely caused by a combination of true bone pain from the affected spinous processes actively touching and inflaming each other, along with activation of local nerves in the regional soft tissue.

Over time, these horses learn to brace themselves with the musculature of the back, says Dr. Davis. This is essentially a secondary muscle spasm that in itself can be quite painful.

What Causes Kissing Spines?

Some experts believe as many as 20 to 30 percent of horses have some degree of kissing spines. It can affect nearly any horse of any breed pursuing any discipline. However, says Dr. Davis, “Horses with a long back tend to be predisposed, especially if they also have a sway back. That combination gets a lot of horses into trouble when they start to lose core strength and muscling. The resulting inverted back conformation naturally places all of the dorsal spinous processes closer to one another.”

Kepferle concurs, noting that Anakin is long in his back and tends to become weak over his topline without proper stretching and strengthening exercises.

Dr. Davis finds that horses used in a discipline that involves inversion of their topline during athletic activity are also at greater risk to show symptoms of the disorder. These include, for instance, jumpers or eventers who invert their backs on landing or barrel racers who invert their backs rounding a sharp turn. In addition, he says, “A heavy rider as compared to horse size, a poorly fitted saddle and a rider bouncing around are definitely things that can exacerbate symptoms.”

Asking for too much collection or engagement when a horse isn’t physically ready for it can increase the pain, says Dr. Davis. “Horses should be mature, well-muscled and conditioned for functional core strength before pursuing advanced athletic endeavors that may injure the back.”

That’s one reason Kepferle always made sure not to ask Anakin for a high degree of engagement during every ride. “It’s only now that he’s 11 that he’s finally strong enough to start working on collection,” she says. “He’s just now ready for dressage at the Advanced level. If I’d tried to do a lot of collection work earlier, he wouldn’t have done so well. You don’t skip the steps—that’s a big, big thing.”

The Symptoms

So, what are the signs that a horse might be suffering from kissing spines? In general terms, think of pretty much anything that might indicate back pain.

“The symptoms can be super broad,” acknowledges Dr. Davis. “[With] some of the horses, people will detect sensitivity when brushing over the topline. A lot of these horses get a lot of spasms in their regional musculature alongside the spinous processes.”

“One of the most characteristic things we hear about is intermittent, severe bad behavior,” he continues. For instance, a jumper may land after a fence and kick out, run off or buck. Or a horse may get sour and have an overall negative work attitude.

“Watching them, you’ll see them travel with a rigid, stilted back and see them carry themselves like a board,” says Dr. Davis. “Sometimes you can see that with a rider, but sometimes you can see it when free longeing.”

Other red flags might include a horse being unwilling to bend in one direction or refusing to take one lead, dragging a rear toe, refusing to accept the bit, decreased range of motion, fidgeting during grooming, nipping when the girth is tightened or bolting when the rider sits in the saddle. Symptoms may sometimes show up suddenly, even though the kissing spines have probably been there for a while.

For Kepferle, a sore back—along with difficulty bending—had been Anakin’s baseline since she bought him, including the tightness and spasms. But behavior issues simply didn’t come up. “There was nothing he said ‘no’ to,” she recalls. “There was never a moment when I felt like something was preventing him from doing the job I wanted him to do.”

Diagnosing Kissing Spines

For the first year and a half after purchasing Anakin, Kepferle worked to address his back issues with saddle fit, chiropractic work, acupuncture and MagnaWave, a type of electromagnetic therapy meant to stimulate cell metabolism to increase blood circulation while reducing pain and inflammation.

While Anakin’s topline began to improve, Kepferle realized he was still experiencing chronic back soreness. “He was so stoic, I knew that if he was showing mild discomfort, it was probably worse than it seemed.”

Ultimately, she contacted her vet, Jan Henriksen, DVM, of B.W. Furlong and Associates, who had been giving Anakin regular care and was working with Kepferle on measures to relieve the gelding’s back soreness, such as saddle fit, workload and even Kepferle’s own fitness and riding. Together, they decided it was time for X-rays.

“It looked way worse than we expected,” says Kepferle. “He’s touching in almost every vertebra in his back.”

Dr. Davis acknowledges the importance of X-rays in diagnosing kissing spines but also says it isn’t typically the first step when assessing a horse with a suspected case. Instead, he’ll start by evaluating the horse’s conformation and topline muscling, then proceed to a complete lameness exam. “It’s important to rule out lameness that may be a piece of the puzzle,” he says.

Along with palpation of neck, back and legs, he’ll watch a horse move on a straight line and at trot and canter on a circle. He’ll look for indications of pain or muscle spasm on palpation and how the horse uses his back in motion.

“For a lot of horses, there will be a behavior seen exclusively under saddle, so an under-saddle exam is important, too,” says Dr. Davis. Since it can be difficult to recreate that behavior exactly during the moment of the exam, owners will often share videos of their horse exhibiting the problem behavior. “Once I feel confident the problem is localized to the back, radiographs are the intuitive next step to rule impingement in or out,” says Dr. Davis. Specifically, the vet will do lateral spinal radiographs—X-rays taken from the side that will show the distance between the spinous processes.

“If I find sites that are touching, overlapped or close—anything suspicious—then the next step is usually to block those sites,” says Dr. Davis. In blocking, the vet will inject a small amount of local anesthetic on the left and right sides of the impinging sites, essentially numbing the suspected area.

“If the horse’s [symptomatic] behavior is bad enough or consistent enough, I can recreate whatever scenario exacerbated the signs and, ideally, see an improvement [with blocking],” says Dr. Davis. “In some horses, it works wonderfully. There is a subset of horses that will partially respond. But it is important to consider that a lot of horses have a resultant generalized or spasmodic back pain that may not fully respond to that small regional block.”

In the situation where kissing spines are still the prime suspect but blocking doesn’t give firm proof, a therapeutic trial may be the next step. In essence, the vet will try a conservative treatment—a local cortisone injection. After the injection, Dr. Davis recommends two to three weeks of stretching and core strengthening exercise (some on the longe and some in-hand, but with no rider for at least the first one to two weeks) and sometimes muscle relaxers. This gives the affected area a chance to relax and for associated inflammation and pain to diminish.

After the rest break, says Dr. Davis, “we put the horse back to work and look for signs of improvement.” A dramatic improvement of symptoms supports the theory that kissing spines, or at least back pain, are a significant contributor to the horse’s problem, he adds.

If the horse doesn’t show improvement to the therapeutic trial, then the owner and veterinarian must consider whether the horse’s condition is so severe that he may not respond to medical therapies or if there is another explanation for the symptoms. “In these cases, advanced diagnostics such as ultrasound and scintigraphy [bone scan] may be performed to help rule out other sources of back pain and/or provide further evidence about how active the kissing spines disease is,” says Dr. Davis.

Medical Treatment

For some horses, the cortisone injection and adjustments to the horse’s exercise routine may be the only intervention required, perhaps with periodic re-injections over time. Others may need additional supportive treatment, with the specifics depending on the horse’s individual condition. This may include muscle relaxants, shockwave, MagnaWave, chiropractic work and acupuncture.

In some cases, the vet and owner may decide to try one or more of these treatments before moving on to an injection. For example, says Kepferle, “We started with shockwave—it was the least invasive thing to try.” But after the first of what would have been three treatments, Anakin began to show discomfort. He began swapping leads, which was abnormal for the gelding. “It was almost like, now that he knew we knew, he was asking for help,” says Kepferle.

Having already tried several other noninvasive options, as mentioned earlier, Kepferle and her vet decided the time was right for a corticosteroid injection. That was in 2018. It did the trick—and he didn’t need a second injection until early April 2020.

Physical Therapy

As successful as the injection was, Kepferle didn’t rely on the medication alone to improve Anakin’s condition. Instead, she built his training and conditioning program around stretching and core strengthening—building muscle over his topline and abdomen. “It’s important to be able to recognize physical limitations and find exercises to improve limitations, hopefully avoiding frustrations which lead to behavioral problems,” she notes.

Now Anakin’s routine includes slow and fast hill work. Kepferle notes that all of her horses do some form of hill work, and she always builds up the level of difficulty. For instance, she’ll begin with walking up and down her hill, build to trotting and, for horses competing at Training level or above, progress to cantering uphill.

For Anakin, she also incorporates a lot of long and low work—in the arena or other good, flat footing—where he is encouraged to move forward in a long frame, “over his back” and reaching for the connection, says Kepferle.

She also uses an aquatred (an underwater treadmill) and a lot of in-hand stretching exercises learned from her vet and equine chiropractor. Careful, thoughtful collection work can also be part of a core strengthening program.

Once a week, Kepferle skips under-saddle work in favor of longeing. She uses a variety of aids, including the Pessoa® Lunging System, Lungie Bungie cords and the Equiband® System. She explains that all of them work to encourage the horse to use the back properly rather than moving on the forehand or with a hollowed, inverted spine.

Kepferle cautions that “everyone should do their due diligence to educate themselves on proper use of any of these systems before throwing them on because they can do more harm than good if used incorrectly. Anakin took months to become comfortable cantering on the longe. I made sure to keep him confident and happy and forward-thinking.”

Even if Anakin’s X-rays had come back perfect, Kepferle says she would have followed the same plan simply because of the gelding’s long-backed conformation. That’s an approach Dr. Davis endorses as a path to prevention for people whose horses show X-ray evidence of kissing spines but no symptoms.

Surgical Treatment

If medical treatment and physical therapy fail to improve the horse’s condition, only then will Dr. Davis consider surgical options. “Not because the surgery is fraught with complications or [tends to be] unsuccessful,” he says, “but for a significant portion of these horses, if you’re really on top of the conservative measures, you don’t have to put them under the knife.”

To be what Dr. Davis calls a “slam dunk” surgical candidate, the horse also needs to have strong clinical symptoms, evidence of impinging or overlapping spinous processes and pain clearly associated with that area on the clinical exam. Ideally, the horse will also have shown a positive response to nerve blocking.

“That being said, surgical interventions for kissing spines disease have very good success rates,” says Dr. Davis. In fact, various studies have shown anywhere from 72 to 95 percent of horses return to full work after surgery.

There are three primary surgeries to treat kissing spines.

Interspinous ligament desmotomy. In this procedure, the vet uses X-ray or ultrasound guidance and cuts the ligament running between the affected spinous processes, allowing them to separate from each other. “This is probably the most commonly reported procedure and is nice because it’s minimally invasive and it’s a standing procedure,” says Dr. Davis. “And there are good reported success rates.” That said, he notes that this surgery is best for horses with only a mild impingement. In more severe cases, it can be difficult or impossible to get the surgical instrument between the spinous processes to cut the ligament—and merely cutting the ligament may be of little to no benefit in these cases, he says.

Osteoplasty. During this surgery, the vet reshapes the spinous processes, essentially shaving off some of the bone. “If the horse has bone-on-bone or overlapping bone, we can take out a small segment of the bone to widen the space,” explains Dr. Davis. Simultaneously, the vet will also perform the ISLD procedure, he notes. This is a more invasive surgery with a longer recovery period.

Ostectomy. “This is basically an osteoplasty on steroids,” says Dr. Davis, explaining that this surgery removes more bone. “Instead of just widening the space, we take a bone saw and take out a significant portion of [the spinous process] or remove it almost in its entirety,” he says.

In some cases, the vet may actually perform more than one of these procedures during a single surgery. For instance, says Dr. Davis, “If the horse has four spots involved, I may widen one spot with osteoplasty and do an ostectomy to fix the next two at the same time. It depends on how severely impinging or misshapen or unhealthy the bone looks.”

Ongoing Care

After any kissing spines surgery, Dr. Davis will put the horse on stall rest for two weeks until the sutures come out and the incision is healed. Then he’ll start the horse on a regimen of stretching for two weeks. “In really mild cases, if I just did [interspinous ligament desmotomy], they may be doing physical therapy and some under-saddle work at 30 days,” he says. “If they’re more severe, they may be doing only physical therapy for 60 to 90 days.”

In fact, he adds, “It’s still really important to incorporate the stretches and physical therapy for the duration of the horse’s athletic career.” He notes that this may prolong the effect of injections and the interval between injections while helping the horse stay more sound and supple for athletic activities.

That’s exactly what Kepferle has found. “Training-wise, I’ve always prioritized his fitness and his body comfort over everything else, and then everything else has been very easy,” she says.

Anakin’s weekly routine still includes strength training and MagnaWave treatments. In addition, if he gallops one day, Meg always follows it with a day of work in the longeing rig—and typically jumps him no more than once a week. “If I do jump more than once, the second [session] is very much about strength training, with small jumps, getting him to use his back properly. Galloping I do as much as I need to, but not more,” she adds.

Kepferle notes that when she first bought Anakin, he had virtually no topline muscling. “Now he looks awesome and has a great topline,” she says. “The more topline, the better it can support the spinal processes so they won’t touch as much and [the horse] can work his back in a proper way.”

She says the best advice she ever got about Anakin’s condition was “to ride the horse like he doesn’t have kissing spines. Make sure you’re working them forward and through to help them build muscle,” she explains. “[Anakin] is not a naturally supple horse, and if I never made him bend and do things that are harder for him, he would never have gotten stronger.”

That said, she also pays close attention to his soreness level and will adjust his schedule as needed—for instance, skipping a gallop or giving him another day off. “It’s important that everyone learns how to properly palpate their horse’s back and makes a daily habit of checking before and after every ride,” she notes. When Anakin started feeling sore after gallops in the spring of 2020, Kepferle’s vet injected him again.

When she first learned about Anakin’s kissing spines and how severe his condition was, Kepferle admits she cried for two days. But now, she says, “He is thriving. When we found out about the kissing spines, he was at Prelim, getting ready for Intermediate. Now he’s an Advanced horse.” In fact, Anakin completed the Fair Hill CCI****-L in October 2019 and was poised to move up to the five-star level this year.

Looking Past Kissing Spines

The bottom line, agree Dr. Davis and Kepferle, is that a kissing spines diagnosis shouldn’t necessarily strike fear into the hearts of a horse owner or buyer. “If we see kissing spines on a pre-purchase exam, it doesn’t make me that nervous,” says Dr. Davis. “Most of those horses will be medically manageable. If you do end up going the surgical route, most of them do very well post-op with appropriate management.”

Dr. Davis says that very few horses would need to retire because of kissing spines “if we weren’t limited by finances, advanced age, etc. For horses who were retired for this condition, pasture turnout is the most common result and quality of life for them is good.”

Since discovering Anakin’s kissing spines, Kepferle has talked with many upper-level riders who have competed horses with kissing spines, and she has worked with other affected horses herself. “There are some cases where the horse will be limited in what he can do, but there are way more occasions where the horse will go on and have a successful career,” she says. “That gave me hope. It’s sad to me that so many people pass on awesome horses because of this. It’s totally manageable.”

Kepferle hopes that by sharing her story and encouraging others to do so, she can “help shift the culture and attitude around this condition and give some great horses a shot who might otherwise be overlooked.”

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of Practical Horseman.