Horsemanship is a living art similar to ballet and singing. Living arts survive by the right advocacy of their practitioners. If one generation deviates from the inherited successful (classical) standards, a living art can be derailed temporarily or lost permanently.

Equestrians are the custodians of a living art, and its survival depends on its uncompromised transmission from generation to generation. It is the duty of each generation of instructors to acquire a thorough knowledge of horsemanship and not to reinvent it or replace it by some trick of the month.

I have been actively advocating for a U.S. national riding academy that would supply the knowledgeable instructors—a dedicated priesthood—to be trusted for the education of the future generations of aspiring equestrians. My proposals for such an institution were rejected, mostly on grounds of unprofitability. While that is understandable, it remains regrettable. Writings, courses, meetings, conferences and congresses cannot replace a truly good academy with a systematic, comprehensive program. Riding is a “coaching” art, relying on educators who can tutor and nourish expertise and foster the right virtues and attitudes in addition to teaching riding skills.

The equestrian art is based on science. It must be understood by the mind and by the function of the human intellect. To become an equestrian, one must take a stance in life: devotion and commitment to the horse by practicing the classical principles of horsemanship simply because they are the ones proven to work.

The Role of the Teacher

The obligation of an instructor should be primarily to the art he teaches. I consider teaching an activity for priesthood because advocacy must be the servant of art. We possess inherited wisdom that compels us to witness to it rather than just being “nice” to clients.

Of course, I am not advocating rudeness and insensitivity, as those would be contradictory to the behavior of a mentor. Nice you may have to be, but that is a secondary virtue. Politeness enhances student response and is a fundamental tool in correct communication. However, a judge or teacher must be dedicated to upholding the art he or she represents and do that accurately, without compromise or yielding to fads. Teaching should be animated by the absolute devotion to what we know is right.

The obligation of the teach to the pupil—regardless of the pupil’s age, talent, financial circumstance, future prospects, etc.—should be to conduct each lesson as if you are coaching the next future gold medalist of the next Olympics. It’s not the teacher’s job to teach an art or a science according to talent. It is not our job to punish or reward what we think is talent or lack of it. I hope that in my teaching I never compromised that principle and show by attention, enthusiasm and diligence that each student is worthy of the best we can offer.

Therefore, the job of a teacher is to conduct a lesson impeccably as if it were given to the greatest rider, deserving of the greatest attention in the finest way, suitable to the horse and the rider at that particular time. This concept must be your guiding light. This is the foundation of any and all teaching. When I taught classes in philosophy and diplomatic history and other subjects, I didn’t say “I will use bad vocabulary or exhibit an undisciplined intellect to debase the subject matter just because there may be some dumb kids in this class.” I wasn’t interested in evaluating the worthiness of my students. One must teach always as if to a worthy class.

The teacher’s responsibility includes also addressing the rider’s spirit. The equestrian arts depend on suitable emotional life, acquisition and development of virtues and high ethical standards that do not yield to fads and fashion. I feel strongly about this. You must teach what is correct even if you were to lose some clients who might think that you are old-fashioned. Let them go somewhere else to learn. Teachers are never universally popular, but a good teacher will always have students and a waiting list because he or she teaches to the right-minded people who value expertise and the validation of inherited tradition.

The ethic of teaching—the job of teaching—is to stick up for what you know is right.

Teachers and judges must remain loyal to the principles of the art of riding. Our commitment must remain the promotion of the well-being of the horse to maximize his useful years in service and to unfold and develop his inborn talent and potential. This is what classical horsemanship stands for.

The Measure of a Good Lesson

The horse verifies when teaching and riding are correct. If, at the end of a lesson, the horse is wringing wet and has reared three or four times during the session, you can be sure you have not been taught by a good instructor with classical principles. The horse that ends a lesson relaxed and stretching his neck out and down is contented and without stress. That is a good lesson. So the horse really verifies good work.

The rider has to know the basic principles: The horse has to be calm, straight and forward, in that order. If he is made nervous, constantly disciplined, harassed or uncomfortable in a lesson, he will not be calm and teachable. Driven without alignment and straightness, he will not support correctly and will lack impulsion. If he is forced to run with a stiff body, he will be exhausted and gain ground with choppy, stiff little steps like a hamster in a cage. If this happens, the student should know he is getting a bad lesson. Such misguided riding disregards the well-being of the horse in his terms.

Here are the measuring sticks: The horse must be well-served. He must stay supple and adjustable both in posture and stride. The instructor must explain clearly, and the lesson must make sense.

Instructors should avoid unspecific terms, such as “that was nice.” It is “nice” when the milkman leaves you a Christmas card. In a riding lesson, what is the definition of “nice”? Of course, you should be always pleasant to a student but, in my opinion, it is important to be more specific and instructive with teaching commentary. If we want to be as “nice” as the milkman when he leaves a Christmas card, then, for instance, be absolutely on time.

In the Spanish Riding School, they say, “What you cannot teach in 30 minutes to your horse remains for tomorrow.” And it’s the same with your lessons. In a clinic with 40-minute lessons, you are not supposed to go to 48 minutes and let the next pupil wait. Such behavior violates politeness and sets a poor ethical standard of professional behavior. Students learn valuable lessons from the teacher’s attitude. We are examples to emulate, not to despise.

A philosopher said, “One of the greatest duties of a teacher is not to praise when praise is not due.” However, the teacher should note when things are better, praise improvement and compliment progress. Praise can be right at the beginning of the lesson when the riders come in. You can make an assessment in a few minutes. Ask them to trot and say if they are in a good rhythm or the horse looks balanced, then you can talk about what in the posture and gait needs adjustment. These are the good manners of teaching: punctuality and praise early when you can, but don’t lie.

Teaching the Rider

Riding is a sport because it is done with bodily skills. The body of the rider is the communications medium by which we guide our horses. In its communications there is no neutrality, for whatever the rider does will either build or destroy the horse’s structural efficiency. There is no room for the usual mentality of “I am trying my best” or “Just wait a minute” or “Oh, let me figure it out.” The rider must do it right or cause some degree of wrong from discomfort to pain, from reversing progress to breaking down the horse’s neuromuscular system. The horse is reactive, not proactive. He has no plans, but he will memorize what the rider makes him do. Therefore, the more a rider drills and repeats an exercise wrongly, the more the horse will become an expert at doing it wrongly. Teach only what you want and teach it right. Then you will not need to retrace your steps. All coaching should be knowledgeable, systematic and gradual.

The rider’s seat should be sculpted into a posture on a standing horse and then must be coached to maintain that posture in motion, when it becomes the rider’s position. The position of the rider from his seat bones upward is categorical. That is, once explained and assumed by the rider, it should need only the rider’s self-discipline, devotion and attention to keep it. However, from seat bones downward, that is, the rider’s leg position, being artificial to accommodate the horse’s shape and facilitate its multiple functions, is developmental. The leg position must be perpetually monitored by the rider to stay in the right place and, with time, improve its stretching, draping and aiding facility.

The instructor improves the horse only through the rider, so the riding lesson should focus on the rider. Each exercise the instructor asks the horse to perform is, more importantly, an exercise for the rider. Each shoulder-in, flying change, transition and everything else should be demanding an exacting delivery of the rider’s aids until they are so effective as to become invisible and utterly harmonious with the horse’s movements.

A good teacher does not promote the repetition of poor work, ineffective aids and the repetition of mistakes, but revises his lesson plan. A good coach should plan a lesson guided by goals for that day, but these goals should also be supportive and mindful of goals for the next week, month and year. Having these distant goals as guiding lights, the instructor can change the lesson plan of the day, replacing it with a more suitable one but without compromising the plans for the future.

At the heart of good instruction is the thorough knowledge of the means by which to achieve your goals. The means are many; the knowledge of them must be vast, yet they are not infinite, indistinguishable or interchangeable. The adage, “The end justifies the means” is not valid, for not all means are valid. Only those that enhance the horse’s well-being are acceptable and justifiable. A teacher must know many ways and have many tools that can lead to the desirable goals in the schooling of horse and rider. One must be careful not to replace the means to an end by the very goals one seeks to achieve. For example, when seeking greater impulsion, we ought not run the horse off his feet at a high speed. In fact, impulsion born from increased strength and improved skills in the use of the haunches results in a slower tempo until the joints are “lubricated” and the balance shifted towards the haunches, none of which can be achieved by rushing and speeding up. The means are never identical to the goals that they are aimed to achieve.

The horse has two teachers, the rider and the coach. If the rider is weak or faulty, you have to correct her first, so that the two of you can address the horse better. The horse cannot work better than what the rider allows. Aiding is the opposite of hindering. The rider, on the other hand, cannot to better than her skills allow. You cannot train a horse to go Third Level if the rider is allowed to stay at Training Level. You have to advance the rider faster than her horse because the rider is the first “tool kit” with which you improve the horse. Do not forget that every exercise is primarily for the development and perfecting of the rider and, only as a result of that improvement, transferable to the horse. A transition or a two-track movement should enhance the rider before it can improve the horse.

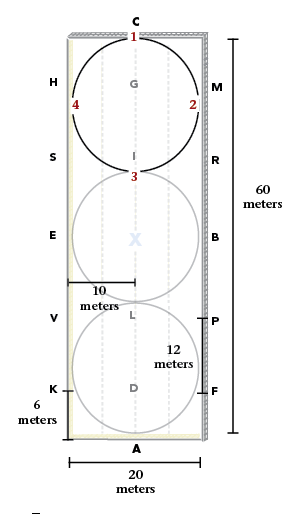

Your second tool kit is the school patterns and their knowledgeable use. How you use the patterns, and, more importantly, how you combine them is what gives your lessons value. If there is any need for bending, impulsion, collection or any other goals, there is a long list of patterns that supply that need. A knowledgeable teacher knows the correct tools.

In an upcoming issue, I will discuss the teacher’s developmental goals.

This article first appeared in the September 2010 issue of Dressage Today magazine.

Charles de Kunffy is a U.S. Equestrian Federation (USEF) “S” dressage judge (retired). A popular clinician around the world, he has taught judges and instructors, particularly in the UK for 30 years. Born and raised in Hungary, he learned to ride from the classical masters at the Hungarian National Riding Academy. He carries on this tradition in his own teaching. Based in Palm Springs, California, he is the author of six dressage books, including Dressage Principles Illuminated and the video “The Art of Classical Dressage.” His website is charlesdekunffy.com.