The horse loves a partner who gives distinct and understandable impulses and aids. This partnership comes from a rider who is relaxed and allows the horse to move harmoniously. But why do many riders have back pain after riding a horse who was unwilling and irritated? Why does the horse frequently not respond to the aids or misunderstand them? To answer these questions, we need an individual and extensive evaluation of the rider on the horse. But before analyzing how the rider moves when riding, we need to evaluate the posture at rest and correct it as needed.

Basic Anatomy

To understand the effect the rider’s posture has on the horse and how the horse influences the rider, we must take a look at the anatomy of the human body. The basic anatomy of the upper body and trunk is most important and is presented simply to make it easier to understand the complex processes in the body. It is as follows:

The vertebral column is comprised of seven neck, 12 chest and five lumbar vertebrae as well as the sacrum and the coccyx. When seen from the side, the spine is shaped like a double “S.” This shape serves as shock absorption under a load.

The vertebral bodies are connected to each other by muscles and tendons, are mobile at the vertebral junctions and are separated by discs. The discs are made of a gelatinous core enclosed in an elastic fiber ring. They also have a shock-absorption function. With the “S” form of the spine, there is good mobility and an elastic spring action that protects the individual structures and enables an effective range of motion controlled by the muscles.

The rib cage protects the internal organs such as the heart, liver, spleen and lungs. It is also important for breathing. It is composed of ribs that are attached to the thoracic vertebrae and in front at the sternum. This structure supports the thoracic spine. The lower ribs are not directly connected to the sternum, but to cartilage. During inhalation the distance between the ribs increases and the ribs are “open.” During exhalation the distance decreases and the ribs are “closed.”

The shoulder girdle consists of the clavicle, which runs from the sternum to the shoulder blade, and connects the arms through the shoulder joints to the trunk, allowing for a great deal of mobility.

The pelvis is comprised of two hip bones that are attached to the sacrum, two seat bones and the pubic bone. Both halves of the pelvis are connected in front by strong connective tissue—the pubic symphysis.

The muscles are responsible for all movement. Some are under our conscious control and directed by nerve signals. Some work unconsciously in circuits for posture control. Muscles can only contract and relax. Consequently, they work in pairs so the previously contracted muscle can come back to its original length in order to contract again. For riding, at the shoulder, you need the chest muscles in front and the antagonist muscles that attach to the shoulder blade and pull back and down. On the upper arm, you need the muscles that raise and lower the arm. At the elbow and the wrist, you need the flexors and the extenders. In the trunk are the lengthwise oblique and diagonal muscles of the back, side and stomach. At the hip, we use joint extensors and flexors and muscles that turn the thigh in and out as well as abductors and adductors. The muscles of the knee, ankle and foot act similarly to the arm muscles.

The whole system of components that carry the body and those that move the body is highly complex and requires the individual components to be perfectly in sync to be able to move at all. How the movement goes is dependent on the quality of the individual components, such as muscle mass, joint quality or tendon and ligament stability, as well as the starting point of the movement.

So is there a specific posture where all actions (muscle tension, movement, relaxation and return) are healthy, effective and harmonious? The answer is yes: It’s erect posture.

Erect Posture

A posture where all the components of your vertebral column and the structures attached to it are in a relaxed position, from which movement in all directions is possible and to which it returns, is considered erect posture. First, we focus on the posture of the head, trunk and pelvis in order to have a basic understanding about the posture of the upper body.

How should you think about erect posture? Your vertebral column should show the so-called double “S” shape to provide the advantages already discussed and to enable movement from a relaxed position. This also optimizes the horse’s movements and leads to a harmonious and healthy coordination between rider and horse.

To keep it simple, the upper body is divided into three building blocks: head, chest and pelvis. These are attached one on top of the other to make the double “S” shape.

– The head building block includes the skull and the neck vertebrae.

– The chest includes the vertebrae of the chest, the ribs, the sternum, the shoulder girdle and the shoulder joints.

– The pelvis building block includes the lumbar vertebrae, the pelvis and the hip joints.

When seen from the front and behind, the line of the shoulders should be parallel to the line of the pelvis. Both lines are parallel to the ground. Any deviation of any of the three building blocks, whether to the front, to the back, to the side or through rotation, disturbs your erect posture and leads to a bad starting position for movement, which in turn upsets your balance and results in an inharmonious interaction between rider and horse.

How to Develop Erect Posture

The following practical exercise describes step by step how to develop erect posture. Practice statically—not on the horse. Control of this posture on a horse or in dynamic movement requires a longer period of practice.

Standing Exercise

1. Stand sideways in front of a large mirror so you can visually check and observe every step of this exercise.

2. Place your feet parallel and a little wider apart than your shoulders with knees slightly bent. This corresponds to the sitting position on a horse.

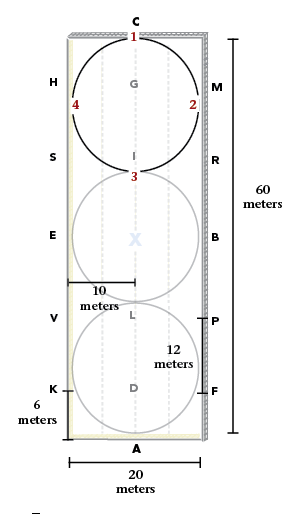

3. Place your hands on the sides of your pelvis and move it forward and back without moving the rest of your body. For this selective pelvis tilt, imagine that your pelvis is a bowl filled with water, and dump the water out forward and backward (see above Illustrations A and B).

4. Find the middle position, where the water in the bowl is level. That is the neutral position of the pelvis, from which you can move forward or backward and to which the pelvis returns. This is the primary movement in riding. The pelvis connects you to the movement of the horse (see above Illustration C).

5. Lift the sternum diagonally forward and up. Imagine that your sternum is pulled diagonally forward and up.

6. Put your hands on the sides of your rib cage and breathe deeply in and out to feel the movement of the ribs. With a deep exhale, the ribs close and the position is held by the tension of the upper abdominal muscles with the sternum pulled as much as possible diagonally forward and up. You are essentially breathing over the stomach (diaphragm) into the sides of the chest and the back area of the ribs (the back). The middle building block is held plumb and remains exactly above the pelvis building block.

7. Let your arms hang loosely beside your body with the shoulder joints in a relaxed neutral position and the shoulder blades pulled down. Imagine that you want to stick your shoulder blades in your back pockets. From the side, your shoulder girdle should now be directly above the pelvis without being behind it. There should not be any rotation in your body.

8. Straighten your head by taking the chin back a little (a slight double chin). The head is now in a neutral position between tending forward and backward. The neck vertebrae as well as the vertebrae of the chest are stretched upward while still maintaining their physiological curvature.

You are now in erect posture—all your movements come from this position. The component parts return to this neutral position after all movement. This posture enables the greatest possible mobility in all directions. An additional advantage is that your muscles aren’t in a shortened position before a movement. This enables the rider to move optimally and to tense or relax with intention.

If you are in a bad position to start with, you will reach the endpoint of your motion quickly. The movement won’t be smooth, and incorrect loading creates tension with possible damage to discs and joints. Since it is also unpleasant for the horse when the rider is tense, he is resistant.

Riding consists of a constant exchange of impulses and signals from both parties. Habitual posture errors and deviations from an erect posture must be analyzed and can be corrected with appropriate and usually simple measures.

First we observe movement forward and backward and orient ourselves on a two-dimensional plane. Our body functions during movement with much more complexity. The concept of the three building blocks can now be used for a simple explanation.

Incorrect Postures and How to Correct Them

You now know how to think about correct posture theoretically. Analysis of individual problems and incorrect postures is imperative. Only when you know your weaknesses and posture errors can you avoid them and straighten up. The following examples can help you to analyze your posture yourself and correct typical posture errors. For a full analysis, I recommend you get help from an expert.

Vulture Neck

When the head building block is positioned forward, we call this a “vulture neck.” Correction point is the chin: Bring the chin back a little (a slight double chin) to bring yourself into erect posture. Make sure that you don’t take the chin back too far (“clamped neck”). Make sure the head building block is directly above the chest building block, and maintain the physiological curvature of the spine. (See Photo A below.)

Clamped Neck

When the head building block is too far back, we commonly speak of a “clamped neck.” Correction point is the chin: Bring the chin slightly forward to get back into erect posture. Avoid an overcorrection. (See Photo B below).

Overstretching the Chest Vertebral Column

When the chest building block is positioned too far forward, we speak of an “overstretched chest vertebral column.” Correction point is the ribs: Close the ribs by exhaling and hold this position with muscle tension. Lay your hands on the sides of your ribs and breathe deeply in and out to feel the movement of the ribs. When you exhale deeply, the ribs close and the position is held by the tension of the upper abdominal muscles. The sternum should be pulled as much as possible diagonally up and out. You are now breathing above the stomach (diaphragm), into the sides of the chest and back. The middle building block is held plumb and is directly above the pelvis building block. Make sure you don’t close the ribs too much (“rounded back”). Make sure the chest building block stays directly above the pelvis building block and maintain the physiological curvature of the spine.

Rounded Back

When the chest building block is thrust backward, this is what we mean when we speak of a “rounded back.” Correction point is the sternum: Lift your sternum diagonally up and out. Be sure not to lift the sternum too much (overstretching the chest vertebral column), but make sure the chest building block stays in the direction above the pelvis building block and preserve the physiological curvature of the spine. The shoulder blades should be pulled back and down.

Hollow Back

When the pelvis building block is thrust forward, the pelvis tips forward and we speak of a “hollowed back.” Two correction possibilities: You can correct from the pubic bone by taking the pubic bone upward toward the sternum (bringing the sternum and the pubic bone closer). Or you can correct from the image of the water bowl, with the pelvis tipped backward so the water is running out the back (see Illustration B on p. 48). Both concepts lead to a neutral position of the pelvis and erect posture. Make sure the tipping movement is not overdone or you will round the back in the lumbar spine. Just get to a neutral position. Maintain the physiological curvature of the vertebral column.

Rounded Back in Lumbar Area

When the pelvis building block is thrust backward, we speak of a “rounded back in the lumbar spine.” Two corrections: You can work either from the pubic bone correction point by moving the pubic bone away from the sternum, or you can imagine that the water bowl in the pelvis is dumping water out the front (see Illustration A on p. 48). Both lead to a neutral position of the pelvis and an erect posture. Make sure the tipping movement is not done too much or you will end up with an overextension in the lumbar spine (hollowed back). Just come back to the neutral position. Once again, the physiological curvature of the spine must be maintained.

Physical Requirements

Now that you have learned what erect posture is and how to get it through correction points, it is very important to constantly strive and practice to make erect posture a habit. Naturally this is all connected with certain physical requirements, which are mobility, stability, coordination and body perception.

Mobility is required to get into erect posture and to get in sync with the movements of the horse. Mobility of the whole vertebral column, the hip joints, the chest and the shoulders can be improved as necessary with targeted stretching and mobility exercises.

The mobility of one region is heavily influenced by the mobility of the neighboring regions. For example, movement of the pelvis automatically requires movement of the lumbar spine and the hip joints. Restriction in the hip joints affects the tipping mechanism of the pelvis and thereby the mobility of the lumbar spine. Restriction of the neck vertebrae influences the entire shoulder girdle.

Without the mobility necessary for riding, movements are distorted and there is no harmonious movement pattern. Verify that you already have the necessary mobility or whether there is need for improvement. You can determine this with videos or photos, for example.

Stability is necessary for maintaining erect posture. Posture weaknesses and errors can be corrected by targeted strengthening of specific muscle groups. For example, powerful abdominal muscles compensate for the tendency to hollow the back. Powerful back muscles compensate for rounding the back. The lateral trunk muscles center the back and the pelvic floor muscles stabilize the pelvis and trunk from within. The inner leg muscles (adductors) provide a stable seat and are likewise important for signaling the horse.

Without the necessary ability to stabilize yourself for riding, movements won’t be smooth, you will get tired quickly and there will be no harmonious pattern of motion. Check to see if you have too much muscle tone or perhaps your muscles are too weak. Some muscles need a lot of strength to create movement and others stabilize joints or the trunk.

Coordination refers to the ability to move the body by means of constant changes from muscle tension to relaxation and the adjustment between mobility and stability in every position of the body and in relation to the immediate environment (i.e., when on a horse). Coordination can be improved through targeted practice of the same movement pattern in various types of sport and, ideally, with music. Since riding is a rhythmically repeated series of movements, dance is particularly helpful. The most important coordinated capabilities of the body in riding are a sense of balance, the ability to balance, spatial orientation, the ability to react, the ability to anticipate and dexterity.

If you can’t coordinate your own body, you will not have optimal control over any movement series. This makes it very difficult to give correct signals to a horse.

Body perception is the most important requirement for erect posture because it gives you the information about the present position of your body and whether a correction is necessary. Recognizing incorrect posture is the first step to improving it by using the factors of mobility, stability and coordination.

Body perception helps you to maintain erect posture. In the beginning, you can practice in front of a mirror. Determine deficiencies and use the correction points as already described. After practicing in front of the mirror, the visual check will be replaced by an improved inner feel for your body. It is helpful to have regular checks by partners, teachers, physiotherapists or video and photo analyses. It would be ideal for you to practice while standing first and then taking the posture you have learned to the horse.

Without good self-perception, you can’t recognize and improve errors. Only a good deal of self-criticism as well as consciously fixing your own body can make you into a good rider and enable a dialog with the horse. All four components should be in harmonious balance and equally developed. When one requirement is missing, the pattern of movement is distorted.

In a Nutshell

A small posture error while standing still is worse in movement. The worst of all is how it affects the rest of the body when riding the horse. Well-trained horses react with sensitivity to the rider. Poor posture can cause contradictory signals, distorting responses and the normal flow of movement. A rider with a deficient seat cannot improve a poorly trained horse. The blame is not on the horse, but on the seat and posture of the rider. Only when the rider is in an erect posture can she give the horse logical aids and receive and send back impulses from the horse with sensitivity. From an erect posture, you can gently moderate a horse’s deviations from correct movement and actively correct him with soft pressure.

Click here to read more articles with Anja Beran.

In her book, The Dressage Seat; Achieving a Beautiful, Effective Position in Every Gait and Movement, German trainer and author Anja Beran breaks down the physical requirements of the rider’s seat on the horse. She offers a unique perspective on the use of breath when riding and explores the need for an improved inner attitude in order to truly refine the rider’s seat. In the following excerpt, Beran works with physiotherapist, dance and gymnastics instructor Veronika Brod to help riders understand their own anatomy and how it affects their riding. This excerpt is used with permission from Trafalgar Square Books. The book and the DVD of Part I are available through www.EquineNetworkStore.com.