Last month, in Part 1 of this two-part series, we discussed how to gain the trust of the young horse and guide her toward becoming a successful dressage mount. The focus was on a filly, MW Angelika (“Angel”) owned by Canadian Grand Prix dressage rider Shannon Dueck, and the steps taken to establish her trust in humans. The steps included Angel’s early lessons as a weanling and, later, the various training methods used to continue her education as a 2-year-old.

In Part 2 of “The Kindergarten Years” we look at another young horse named Sieg, a Hanoverian gelding owned by Adult Amateur Amber Fies. We follow Sieg’s early start at Hilltop Farm in Colora, Maryland, to his breed-show experience and eventual transition to living at Fies’s private farm. The common theme within Angel and Sieg’s stories is the importance of starting early and working with the young horse to establish trust, relaxation and respect―through patience, not fear―and how this solid foundation can establish the horse’s future career.

Case Study: Sieg

Fies is an amateur owner with young-horse experience: She helped raise three homebred foals and later worked for a hunter/jumper trainer, starting young horses under saddle. She purchased her future dressage horse, Sieg (Sir Gregory x SPS Diorella/Donnerhall), before he was even born three years ago from the breeder, Kendra Hansis of Runningwater Warmbloods in Frenchtown, New Jersey.

The Right Start

From the beginning, Fies recognized that most boarding facilities lack the ideal conditions to raise youngsters. So she sent Sieg as a weanling to the Young Horse Raising Program at Hilltop Farm, where she was fortunate to get one of the limited openings for outside clients. Hilltop has experienced staff and provides the safe, nurturing and natural environment that Fies considers essential.

Training at Hilltop, as at most active breeding facilities, begins as soon as the foal is born. “The foal has to learn to respect people and their personal space early on―not from fear, but through establishing boundaries,” explains Natalie DiBerardinis, Hilltop’s general and breeding manager. A newborn is handled immediately and wears a halter on the second day. After a few weeks, Hilltop separates the mare and foal into adjacent feed stalls, teaching the foal his first lesson in independence.

Breed Shows

As a yearling, Sieg was prepared for breed shows by Quinnten Alston, the stallion and breed-show handler at Hilltop. Alston notes that the youngster might come in from the field with a buddy, a young horse from a different field, or alone. He handles them in the indoor arena or takes them on walks around the farm. Variety and change are essential as is an assistant to encourage a forward mentality in the youngster and resolve any problems. If the youngster’s attention is lost, Alston focuses on moving the horse’s hind legs forward and sideways. “In doing this, the horse then becomes more relaxed,” he says. “It gives him a job and makes him tune in to me rather than on whatever is new and different.” Alston carries a small dressage whip, but resolving problems is more about controlling the legs, directing the energy and keeping the youngster attuned to the handler’s body language.

.jpg)

Preparing a young horse for breed shows takes time, says Michael Bragdell, head trainer at Hilltop. He is amazed when inexperienced owners take off with their yearlings “like a bat out of hell,” trying to mimic the professionals at horse shows. “It’s great they want to do that,” he says, “but it’s best to build strength and understanding first. If you’re sitting on your green-broke 3-year-old, you aren’t going to go across the diagonal and do a medium trot.”

On the other hand, some owners overprepare. “These owners have worked their horses every day for the last three months so the work is no longer fun for the youngster,” says DiBerardinis. “Every time someone interacts with a young horse, that youngster is learning something. Babies have a short attention span, so in general I think whatever we are doing with them tends to be in short 10- to 15-minute segments [even less for foals].”

Hilltop handles its young horses daily, but grooms only a few times each week. Youngsters also have their manes pulled, are clipped and see the farrier every four to six weeks, depending on their age. Additionally, every time a youngster is moved to a different field on the farm (usually twice a year) he is trailered. “This takes a lot of time but it’s not training for shows—it’s time focused on basic manners and finding comfort in different experiences,” says DiBerardinis. “Horses that are actually going to breed shows get more work leading up to the show—perhaps four to five pre-show sessions specifically with Alston handling them, although it could be less. It just depends on each horse and what they need.”

When teaching a young horse how to work on the triangle, Bragdell always starts in a slow tempo and never begins by trotting the whole triangle. He trots a short side of the arena and then walks. Then he walks half the long side and trots the second half with the corner helping slow the horse down. (The corner also allows the handler to catch his breath!) While youngsters track right on the triangle at breed shows, Bragdell and Alston first teach the yearling by going left in the arena, so the handler has the wall as a border to keep the horse straight and paying attention. “It’s a good way to get the horse to respond to our body language and how we move,” says Bragdell. “For example, if we want to move big, we walk big. If we want to trot small, we trot small.” The handler creates the triangle, piece by piece over multiple sessions, and finally the youngster trots the entire pattern. Bragdell compares it to training a competition horse. “You don’t actually have to ride your dressage test right away,” he says. “Instead, you might work on your canter departs and do one step at a time.”

Bragdell incorporates some of the work of Australian dressage rider and trainer Tristan Tucker before starting youngsters under saddle. Tucker’s Response Training system (TRT Method) consists of ground-work patterns, used on and off the horse, to relieve tension (see sidebar on p. 54). Tucker then introduces touch, sound and movement (plastic bags, waving flags, tarps, etc.) to create a pressure situation. The horse has two choices: to flee or to relax in the patterns and postures that give comfort and confidence.

For Tucker and Bragdell it is all about directing the horse’s legs. “If I am able to direct the legs of the horse, it doesn’t matter what distractions are out there,” says Bragdell. “It’s just another object and they eventually learn to just wait for my next signal.” Tucker’s basic ground-work patterns teach the horse how to carry himself by asking him to step away from the handler by crossing the inside hind foot in front of the outside hind foot. Next the horse is taught to cross the inside front foot behind the outside front foot. Each pattern is done in both directions with the horse walking in a small circle around the handler. The exercise moves the horse’s shoulders, bends the body and allows the horse to lower the head and neck and become relaxed. It gives the horse a place of comfort when scary objects or situations arise.

Hilltop youngsters get to see plastic bags, umbrellas, tarps and other fun toys. It is all part of the training. “But you have to understand what you’re doing,” says Bragdell. “It’s like a saddle. A saddle can be just like a plastic bag. If you don’t know what you are doing with it, you can create a lot of problems in the training process.” Never force the youngster toward an object or scary situation, generating tension, but instead go slowly, break it down into simple steps and find relaxation in the exercise.

TRT Method: Tristan Tucker

Tristan Tucker’s Response Training system (TRT Method) aims to better prepare horses and riders mentally and physically for challenging situations. He believes sport horses need to learn at an early age how to cope with the human environment and the pressures of a competitive career. The TRT Method consists of groundwork patterns and exercises, used on and off the horse, to relieve tension. Tucker then introduces touch, sounds and movement to create a pressure situation. The horse has two choices: to flee or to relax in the patterns and postures that give comfort and confidence. He calls it “yoga for horses.”

The first ground patterns teach the horse how to carry himself by asking him to step away from the handler by crossing the inside hind foot in front of the outside hind foot. Next the horse is taught to cross the inside front foot behind the outside front foot. Each pattern is done in both directions with the horse walking in a small circle around the handler. The exercise moves the horse’s shoulders, bends the body and allows the horse to lower the head and neck and become relaxed. It gives the horse a place of comfort when scary situations arise.

Tucker emphasizes the importance of beginning the learning early, soon after the foal is born. “It is important to start young so they are not left to develop strong natural instincts of survival. Instead, you can give them knowledge of how to exist in the human world,” says Tucker. “You give them education when they are at home so they can trust their education when they are away.”

On Your Own

Sieg stayed at Hilltop for more than a year until Fies and her husband purchased property for their horses. While his training progressed smoothly at Hilltop, Sieg started testing Fies once he was at home. For instance, one day he would be quiet and cooperative while Fies led him to and from the fields, but the next he would rear or try to run her over. Fies prevailed with a technique learned at Hilltop: She used a 14-foot rope attached to the halter and waved it at him but did not touch him with it. This is one of the first steps of the TRT Method. “You don’t want to create fear, you just want them to respect your space,” she says. The rope helps back the horse away from the handler. Once the horse responds by backing up, the handler stops waving the rope. Fies does recommend that handlers wear a helmet, sturdy shoes and gloves in such situations.

Another issue that Fies encountered with Sieg was his occasional resistance to going into his stall or walking out of the barn. “He would plant his feet and not want to move,” says Fies. Here, patience is needed and assistance is helpful. “You never want to pull a horse forward,” warns Fies. Instead, she applied a small amount of pressure on the lead and faced forward, in the direction she wanted him to move. As soon as he made even the slightest movement forward, the pressure was released. He soon understood what was expected of him. It can also help to have someone behind the horse lightly tapping him with a whip. Again, as soon as there is any forward movement, the tapping must immediately stop. Otherwise, the youngster will not understand what you are asking of him.

Along with the routine tasks of daily handling in Sieg’s new home, additional experiences were added. Cordless clippers were used, first letting Sieg see and feel them, then hearing the noise, then clipping his legs—a little at a time over multiple sessions. Sieg was led over poles to help his coordination, balance and obedience. Fies took him on walks alone away from the barn and other horses to see new scenery, to visit the neighbor’s cows or introduce him to unfamiliar objects. “I think it is good for a horse mentally to be outside of the arena as it gives him something else to think about,” says Fies.

Fies cautions not to tire or overtax a young horse with new lessons, as their concentration is limited. She is a big proponent of changing routine so youngsters accept flexibility. Fies is quick to offer verbal praise, but refrains from giving treats, which can lead to biting and future problems.

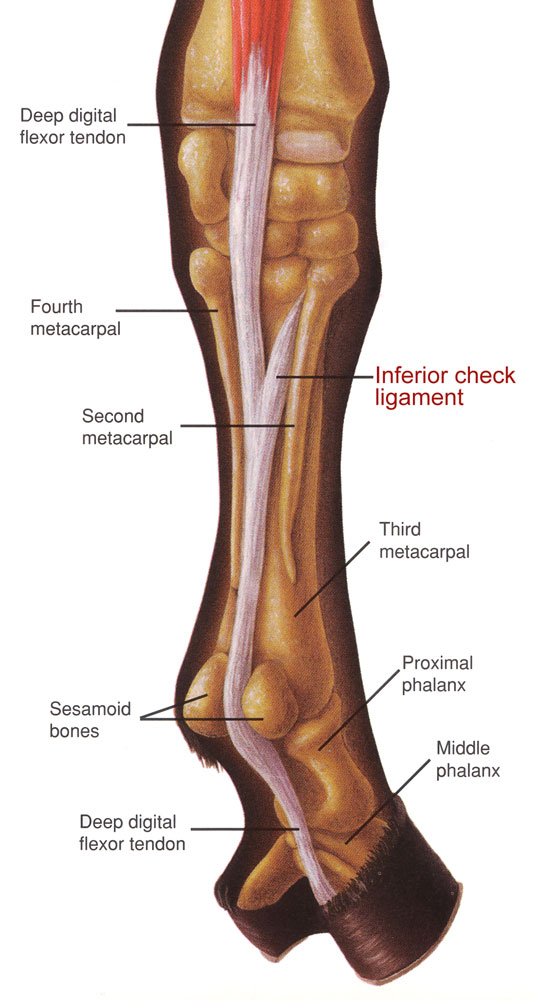

In preparing for the breed shows as a 2-year-old, Sieg learned to wear a bridle―first with the bit soaked in apple juice without a noseband or reins while standing in his stall. The pleasant taste of apple juice encouraged Sieg to accept the bit while the lack of a noseband allowed him to have full range of motion of his temporomandibular joint (TMJ). “We don’t want to introduce any discomfort or restriction to the horse,” comments Fies.

Next, Sieg was led with a halter over the bridle and then with the noseband and reins attached, which prevented any pressure on his mouth if he acted up. Once Sieg accepted the bridle and bit without fussing, he was led around with the reins and no halter. The process took several weeks. Fies also revisited Hilltop, where Alston refreshed Sieg’s show-handling lessons. This included walking and trotting on the triangle, respecting Alston’s space and moving at the rhythm that Alston set.

Fies will wait until Sieg is 3 to begin limited longeing with a focus on long-lining and then backing him later in the year. “Everyone is in a rush,” she exclaims. “Even if the youngster appears physically mature, he still may be growing, and starting too early will put premature wear and tear on the horse.”

There is much to be learned during the kindergarten years in preparation for the riding work to begin. Young horses need free time in the field to play and learn herd dynamics. But these years also present a unique training opportunity. “Every time you put your hands on a young horse, it is training,” says Bragdell. “Basic handling―grooming, being touched, fly-sprayed and clipped―and establishing trust, those are big pieces. If this has all been done, the starting process is so much easier. It makes a tremendous difference.”