Q: My Lipizzan mare is not going forward well—the walk and trot are quite slow and feel labored—so I started to ride with spurs. The result is that she now resents my legs and kicks out with one of her hind legs when I apply the spurs. Plus, she still won’t go. How can I get her to accept my driving aids? She is coming 5. I had a scintigraphy done on her, but the vets said there is nothing wrong, medically. I have ridden dressage for decades but have no experience with young horses.

A:

There are several possible explanations for your horse’s resistance to forwardness. By exploring each potential issue, you should be able to eventually solve the problem in one of the following ways.

(Arnd Bronkhorst – arnd.nl

)

A good first step for this kind of problem is to have a comprehensive veterinary check. Health issues like equine anemia and Lyme disease can greatly affect a horse’s natural forward-thinking process and reveal themselves as resistance to forwardness. Make sure you consult with your veterinarian to explore other possible physical issues that may render a horse less forward thinking.

Secondly, a young horse can change in her body as a result of work. I often find that resistance to forwardness can be the result of poor saddle fit, particularly in the shoulder area. I often recommend that riders working with a young horse’s changing body work closely with a reputable saddle fitter who can routinely assess the fit. Quarterly checks are adequate to ensure that the saddle is speaking to the morphing body.

Often much of the resistance can be resolved through groundwork. It is well worth your time to educate yourself in advanced groundwork methods. Groundwork is not only the art of connecting deeply with a horse, but allows you to work with the horse’s balance and suppleness and establish communication without the weight of the rider. Ground-based exercises that assess the horse’s physical comfort are especially important.

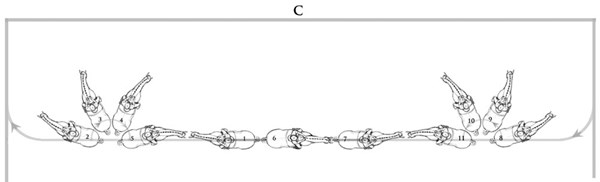

Longeing to establish voice cues can be a good place to start with your horse. It is also a good place to start tuning in to her mental readiness. Before every ride, a brief longeing session can also remind your horse that a cluck means “forward.” Once you are in the saddle, you can use the cluck and pair it with a subtle tap of your legs. Eventually, you would not require a cluck but simply a mild touch with your legs for forward.

The caveat to this is that your mind must be forward-thinking. Forward energy is not only a physical thing, but also needs to be matched by a mental state. Often I find people asking their horses for forward energy from a mechanical place (i.e., spurs), but may lack mental energy and commitment. When we fail to match our leg request with mental awareness and engagement, our muscles may tighten without us being aware, which would give the horse the opposite indication we intend.

A young horse may question a request if she senses us bracing in our bodies, because that indicates to her that we are hesitant or fearful. If we seem to be hesitant or have an underlying fear to do what we are asking, our horse will certainly resist as well.

It is important to become aware of the signals we are constantly sending to our horse through our own body language and mental energy. Often we may unwittingly give the horse a mixed message by intentionally requesting one thing with an aid while our unintentional body language and energy communicate something entirely different. For example, if we request forwardness with a cluck, tap or spurs, but lack sufficient openness in our body and/or mental engagement, our horse may become confused, dull or even surly, unsure of how to correctly respond.

Remember, the horse is by nature a forward-thinking creature. He has one of the largest amygdala of any mammal, which is the part of the brain associated with the flight response. Therefore, when there is resistance to forward motion, one must always look at what might be preventing him from wanting to move.

Another possible culprit for lack of forwardness can be an uneducated hand. Young horses are just beginning to learn how to trust the rider’s hand and reach into the bit. This requires a very giving hand—one whose timing is correct and consistent. When working with a rider who has little experience riding young horses, I have often found that her hands may be sending the horse conflicting messages. For example, she may be balancing on the horse with her hands, which prevents a light rein in the front to ensure that the horse’s energy propels her from the back of her body forward.

A young horse may need to be ridden in a more open frame than an older, experienced horse—slightly in front of the vertical and thus allowed to move more freely. Even a subtle closing of the fingers or tightening of the forearm can discourage forwardness. This is like pressing the gas pedal and brake at the same time: The car will go nowhere. It is often helpful to work alongside a professional trainer experienced in starting young horses to serve as a periodic guide on the ground to ensure that you are progressing along.

Ultimately, we must come to our horse believing deeply that she wishes to please us and spend time with us. Therefore, any resistance a horse may exhibit is simply the horse expressing some degree of physical or mental discomfort. It is up to us to determine what that is and continue to build a relationship where the horse enjoys her time with us in all we do together.

Maria Katsamanis, PhD,

holds a doctoral degree in clinical psychology and maintains an appointment as clinical assistant professor at Rutgers Medical School in New Jersey. In 2016, she established The Pegasus Foundation with the mission of rehabilitating horses. Her background in biofeedback and psychophysiology is central to her training approach, dubbed “Molecular Equitation,” which examines the connection between horse and rider on a molecular level and focuses on improving such basic elements as balance and relaxation, muscle formation and breathing behavior to dissipate physical blocks and facilitate communication.