If you have watched dressage on the international stage, you know it can appear deceptively simple. Caught up in a spectacular performance by horse and rider, we can forget that what we see is actually both a perpetual work in progress (living art) and, in a more practical vein, a final product of sorts. A horse and rider performing at this level are the result of not only the best training, equine management, veterinary care and equipment selection, but also—perhaps most essentially—of the selective breeding of the modern sport horse.

When we watch top international horses perform, we wonder: Were these horses just born for this? If so, how has their breeding shaped their destiny? What can we learn about the sport of contemporary dressage by taking a close look at the bloodlines of those horses who have done it best? In this 2018 article series, Dressage Today will highlight 11 of the world’s top dressage horses from the FEI world-ranking list, taking a close look at their pedigrees and associated breed registries. To gain insight into the horses’ lineage, DT will talk with experts on international sport-horse breeding, representatives of both breed registries and sport-horse organizations and, in some cases, the people who know these horses best—the breeders, owners and riders themselves.

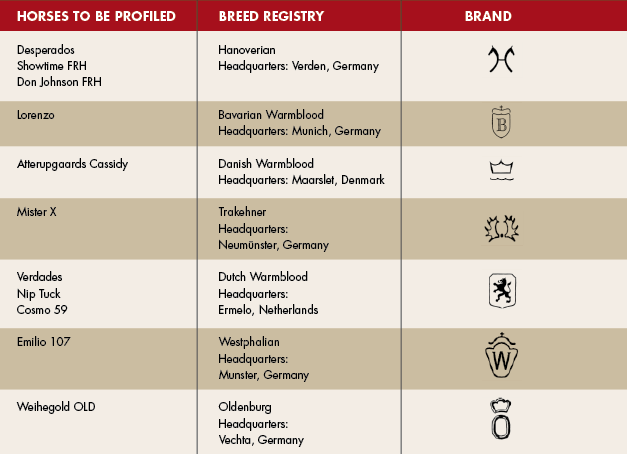

Among the “Top 11,” there are seven European breed registries represented: Hanoverian (three horses), Dutch Warmblood (three horses), Oldenburg, Westphalian, Bavarian Warmblood, Russian-bred Trakehner and Danish Warmblood. Therefore, in this first article in this series, we will provide an overview of the European breed registries, which will later help us interpret what we learn about the breeding of 11 of the world’s most successful dressage horses.

What is a Warmblood?

It’s widely understood that the general term “warmblood” refers to horses who are neither hot-blooded (Thoroughbred or Arabian) by breeding nor cold-blooded (draft). However, in the context of equestrian sports, warmblood infers horses descended from the deliberate breeding of the European riding horse. Today, a widely accepted definition for “warmblood” is a horse with at least four generations of documented sport-horse bloodlines that has been inspected and registered by a recognized breeding association with the purpose to excel in the sports of dressage, eventing and show jumping.

In the introduction to The International Warmblood Horse: A Worldwide Guide to Breeding and Bloodlines, author Jane Kidd writes: “The warmblood has never been a pure breed; it has always been defined by area—Swedish, Dutch, Holstein, Westphalian, etc.—and a foal is usually registered where it is born.” Kidd goes on to explain that the breeders of each particular region/nation have sought to produce the best possible riding horses for their region, valuing qualities such as athleticism, soundness and good temperament. Therefore, because warmbloods of a particular region are actually a “breed population” (as opposed to a “pure breed” like the Tennessee Walking Horse or American Quarter Horse), warmblood breeders are able to selectively incorporate outside stock into their registry in order to improve the foals being produced for their intended purpose.

Celia Clarke bred warmblood sport horses for more than 40 years and co-authored The International Warmblood Horse with Kidd. She was the Stallion Grading Secretary of the British Warmblood Society (now the Warmblood Breeders’ Studbook U.K.) from 1984 to 1991 and currently operates a breeding consultancy. According to Clarke, “Today, the traditional warmblood studbooks do remain district-based, particularly in Germany. But because of the commercialization of studbooks, more and more studbooks operate not only in their regions of origin but also in other regions of Germany, throughout Europe and internationally. They have what they call ‘daughter studbooks.’ For example, we have the British Hanoverian Horse Society in the U.K. and there’s the American Hanoverian Society in the U.S. Both are daughter studbooks of Germany’s Hannoveraner Verband.” Clarke defines a “warmblood studbook” as an organization recognized by the World Breeding Federation for Sport Horses (WBFSH).

A Historical Perspective

Clarke’s husband, John Clarke, is a professional historian and former chairman of the British Warmblood Society. According to him, Germany’s history as a nation influenced the development of regional systems for breeding and registering warmbloods. He explains: “It’s important to understand there wasn’t actually a German state until 1871. Before then, there were more than 30 independent states in what we now think of as Germany. Going back several centuries, horse breeders were encouraged and supported by the individual states in the breeding of horses largely intended for military purposes.” Breeding practices were driven by the core philosophy that horses of a particular region should be bred so as to best meet the current needs of that region’s human population.

“The warmblood has never been a pure breed; it has always been defined by area— Swedish, Dutch, Westphalian.”

John Clarke explains that this regional approach (and core philosophy) has carried forward into contemporary breeding practices. He says that even under unified Germany, individual states still have fairly independent authority over certain matters, among them the regulation of agriculture, including horse breeding. (He adds, “much more so than individual states in the U.S.”) Post-World War II, the use of warmblood horses for military and farm work became less relevant and their use for sport and leisure/recreation became much more prevalent; Therefore, European warmblood registries shifted the focus of their breeding programs to produce warmbloods capable of meeting the population’s evolving need for superior riding and performance horses.

Registry vs. Studbook

A registry is an organization that records the identity of a horse (e.g., registers its existence) but does not necessarily also record the breeding, grading, branding, etc. of the equine concerned. These more specific details go into the studbook, which is kept by the registry but is almost certainly now kept in exclusively electronic database form rather than as a published (stud) book as in earlier pre-computer times. However, many registries (and certainly all reputable warmblood and sports-horse registries) only register horses who have proven parentage. The sire and dam have both been graded into their own breeding studbook or another one that they recognize of equal standing. (They are therefore automatically entered into the relevant studbook upon registration.) The word “studbook” is now used interchangeably with registry, where the registry is the office that does the registration and the studbook is the data source in which the registration of the horse is recorded.

—Celia Clarke

How the Registries Operate

The flexibility to incorporate broad bloodlines into the stock of a single registry offers both enormous potential for ongoing evolution of the breed and incredible responsibility to evaluate the outside lines being introduced. Quality control is a top priority. This has led to a system of inspecting, approving and registering warmbloods that is definitely intricate and, to the outsider, can seem outright confusing.

Kyle Karnosh has bred warmblood sport horses for more than 30 years at Con Brio Farms in California. Karnosh says that understanding how a warmblood foal gets registered can help one better understand the breed registries themselves. She explains the concept of an open studbook. According to Karnosh, “To register a warmblood foal, it boils down to one very simple rule: Both the mare and stallion must be approved for breeding by the same registry, regardless of their own breed of origin.”

Karnosh explains that while all the registries have slightly different regulations, there are some general registration procedures that apply to most warmbloods. According to Karnosh, “Today, as in the past, inspections are a crucial element of the breeding process for European warmblood breeds, including for those horses bred outside of the region of origin. Once a mare has been inspected and approved by a specific registry, she can be bred to any stallion approved by the same registry and the foal will be eligible for registration.” The subsequent foal will then most probably be put forward for inspection by official judges when still at foot beside his dam, which enables him to be graded, using criteria set forth by the registry (typically conformation, quality and gaits). This system not only allows the youngster to be assessed as an individual, but also alongside his peer group, a vital procedure in a process that relies on identifying the best at every stage. A more highly graded foal might be more marketable if intended for sale. Karnosh says, “Inspection scores are also important because they provide feedback to the breeder: Was this a good cross? Do you want to repeat this cross based on the foal produced?”

In Europe, and especially in Germany, inspection events typically take place annually in the same location—each registry has a home facility. In North America, inspections are more likely to be part of a tour (with officials traveling to multiple locations to perform inspections). At the events, stallions, mares and foals can all be inspected, though the process varies according to the horse’s sex and age as well as by registry. Celia Clarke emphasizes that some of the warmblood registries, both in Europe and internationally, are more open than others (more liberally allowing approvals for horses from outside). For example, it is common for the Dutch Warmblood or Oldenburg registry to approve an outside horse, whereas the Trakehner registry is quite closed, only occasionally approving a Thoroughbred, Anglo-Arab, Shagya or pure-bred Arab for breeding purposes. In addition to inspecting, grading and approving breeding stock, breed registries also serve important purposes such as setting breed standards, promoting the breed, tracking breeding and performance records and acknowledging/awarding top performance horses. When we discuss each of the horses in our Top 11, we will also highlight their respective breed registries: the history, breed standards, practices and traditions associated with each.

Meet Our Top 11

Each of the horses in our Top 11 is a symbol of national or regional heritage as well as representative of the combined efforts of generations of breeders to produce a horse best suited to his job. These horses are purpose-bred and in the case of our Top 11, sport (though not necessarily dressage) is the purpose for which they were bred.

Rather than present the horses in order, we’ve chosen to group them by breed registry, so as to be able to explore similarities and differences in their history and lineage. We chose what horses to feature based on the FEI’s ranking of dressage horses in August 2017, when our research for the series began. (Note that the FEI updates this list monthly, so some of our horses have since fluctuated in and out of the Top 11 World Ranking. Nonetheless, many have maintained a position and all are fascinating representatives of contemporary warmblood breeding.)

We’ll begin next month with the first of our Hanoverians, Desperados FRH (ranked second in the world at the time our research began) and follow in March and April with two more Hanoverians, Showtime FRH (third) and Don Johnson FRH (ranked seventh). In May, we’ll look closely at Lorenzo, a Bavarian Warmblood (ranked eighth). In June, we’ll focus on a Danish Warmblood, Atterupgaards Cassidy (ranked 10th) and in July, we’ll spotlight Mister X, a Russian-bred Trakehner ranked 11th. From August to October, we’ll turn our attention to the three Dutch Warmbloods, Verdades (ranked fourth), Cosmo 59 (ranked ninth) and Nip Tuck (ranked fifth). (When we write about Nip Tuck, we’ll also discuss the pedigree of his world-renowned stablemate, Valegro, whom Clarke calls, “A horse so notable you simply must write about him.”) Finally, in November, we’ll return to Germany and present Emilio 107, a Westphalian gelding (sixth). In December, we’ll conclude our series with the horse ranked Number 1 in the world and the only mare on our list, the Oldenburg, Weihegold OLD.

Identity Issues

Hot-branding was long used both in Europe and internationally for identifying horses as belonging to a specific breed registry. Traditionally, warmblood foals were branded at the time of inspection. The brand symbol represented the breed and logically also signified the region or nation with which the breed registry was associated. For example, the Dutch Warmblood brand features a rearing lion, resembling the Netherlands’ coat of arms. Likewise, the Holsteiner brand closely resembles the coat of arms for the German state Schleswig-Holstein, which features a vertically divided shield. And that of the Bavarian Warmblood features not only a letter “B” for Bavaria but also a small cross, apropos for this region of Germany with its long and devout Catholic history.

In North America and the U.K., registry brands for warmblood horses are often a variation of their European counterparts. For example, the insignia for an Oldenburg registered with the Oldenburg Registry of North America features the German Oldenburg brand, but framed by an “N” on the left and an “A” on the right.

While the brand symbols may be interesting and provide a glint of local culture and history, hot-branding has been illegal in Holland for about a decade and in Germany since 2012 due to animal-welfare concerns. Therefore, warmblood foals born today are much more likely to be microchipped than branded. (However, U.S.-bred warmbloods are still frequently branded.) In fact, European law mandates microchipping for foals and internationally many registries also uphold this requirement. DNA testing at the time of registration/inspection also helps to ensure accurate identity.

Some of the breed registries, such as the Hanoverian Studbook, utilize different variations of their main brand to distinguish the section of the registry into which a horse is registered. For example, a Hanoverian mare registered into the Main Studbook, which requires four generations of recognized pedigree, will be branded with the “H” symbol, while a mare registered in the Studbook, which requires only three generations of recognized pedigree, will be branded with the “S” symbol. Today, these brands may not be physically placed on the mare’s body due to current law. However, the mare’s brand will still be noted on her registration papers as the distinction between the studbooks still applies. In addition, while the brand symbols may no longer be as relevant as identifying marks on the horse’s body in many countries, registries still proudly display these symbols as an official emblem and trademark.

This article first appeared in the January 2018 issue of Dressage Today.