Showtime FRH is listed by multiple sport-horse databases as “a 2006 Hanoverian gelding, dark brown.” Though accurate, this description does not come close to capturing the striking picture that Showtime makes when performing with his longtime rider, German Olympian Dorothee Schneider. Showtime’s coat is a gleaming dark chocolate, his build is leggy but powerful and he has movement that could almost be described as flamboyant if he were not also exceptionally precise in his way of going. According to Schneider, Showtime (whom she calls “Showi”) is “shy in a good way,” but it’s difficult to detect any shyness when the pair commands the competitive arena.

Showtime has been making his mark on the world stage since 2011, when, as a 5-year-old, he was ranked sixth at the World Breeding Dressage Championships for Young Horses. He competed Grand Prix for the first time in 2015 and in the same year, Schneider and Showtime were nominated for the German national team. Multiple national and international honors followed, including team gold at the Rio Olympics.

Showtime caught Schneider’s eye eight years ago when a friend showed her a video of the then 3-year-old Hanoverian who was bred by Héinrich Wecke. “I was already impressed by Showtime,” said Schneider. “As I’ve trained him over the years, I’ve discovered a unique horse. He has three world-class gaits, a very good attitude toward work and one of the most powerful hindquarters I’ve ever seen. He could benefit from a little more self-confidence, but as the rider, it becomes my job to give this to him.”

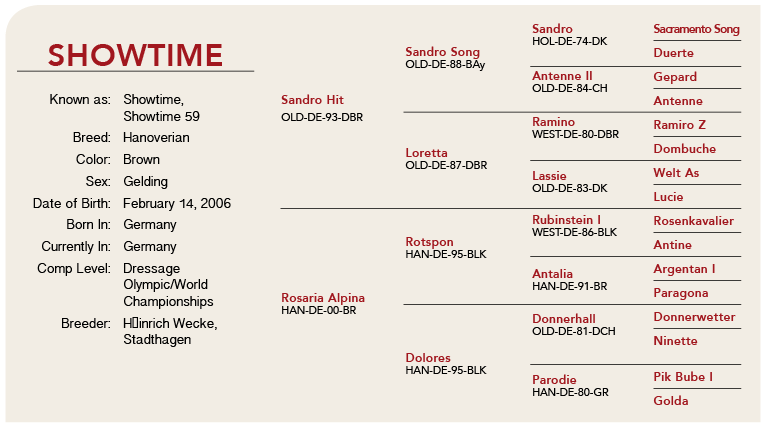

Showtime is by the world-renowned Oldenburg stallion, Sandro Hit, who has been one of the most widely bred warmblood stallions over the last two decades. Sandro Hit descends from mostly jumping lines (his sire Sandro Song and grand-sire Sandro—50 percent Thoroughbred—both reached international levels of show-jumping competition as did his dam-sire, the Westphalian Ramino). Though Sandro Hit himself did not jump well, he was successfully campaigned as a dressage horse and later as a sire of dressage progeny. Sandro Hit and his offspring are known for their impressive movement, dark coloring and striking presence. In these respects, Showtime epitomizes his sire’s progeny. Schneider points out, “Sometimes riders say that Sandro Hit offspring have problems with attitude and are lacking in quality of gait at the walk. Based on my experience, I cannot confirm this opinion.”

Schneider has ridden three horses by Sandro Hit to the international level (Showtime, the Westphalian stallion St. Emilion and the 10-year-old Hanoverian Santiago). Despite this, when asked about Showtime’s breeding, she says, “It was the video of him as a 3-year-old that caught my eye first, not the pedigree. But if you’re interested in sport horses, you always look first to the gaits, then to the exterior and interior of the horse and finally to the pedigree.” Today, she admits some partiality to Sandro Hit descendants, but says that is mainly because of her own personal success with three of his offspring. (Note: Weihegold OLD, the Oldenburg mare ranked No. 1 in the world with rider Isabell Werth, is a Sandro Hit granddaughter.)

Schneider points out that the influence of Showtime’s dam, the Hanoverian mare, Rosaria Alpina, may contribute to Showtime’s good attitude toward work. The mare is by the Hanoverian stallion Rotspon (named 2017 Hanoverian Stallion of the Year by the Hannoveraner Verband), who is by the renowned Westphalian Rubinstein I. According to Schneider, “Rubinstein comes from the most significant dressage dynasty in the world. He made a career for himself in the dressage ring. His genes can be found in practically all of the breeding regions of Germany as well as abroad.” She refers to Rubinstein as the “rideability” sire because his offspring are known not only for their phenomenal performance capability, but also for their good working attitude. (Rubinstein I appears in the pedigree of four of the 11 horses featured in this series.)

Via his grand-dam Dolores (on his mother’s side), Showtime also descends from a notable cross, namely that of Oldenburg Donnerhall (third generation) and Hanoverian Pik Bube I (fourth generation) through daughter Parodie. Donnerhall was legendary both in the competitive arena, where he excelled at the international level, and in breeding circles—he’s known as one of the most successful and influential warmblood stallions of all time, both because his offspring have excelled in international competition and because dozens of his sons were approved as breeding stallions. (If you visit Oldenburg, Germany, you can see a bronze statue of Donnerhall in the city square.) Pik Bube I competed through Grand Prix and is renowned as a sire of both dressage and jumping progeny. He’s duplicated (appears twice) in Showtime’s pedigree on the dam side.

Also of note in Showtime’s breeding is that he’s 9.38 percent Thoroughbred/Arabian in five generations of pedigree, according to Sporthorse-data.com. In addition to the Thoroughbred stallion Sacramento Song (fourth generation), we see influence from the Trakehner breed via Absatz (fifth generation).

In short, Showtime is descended from sport-horse royalty, but one might look at his pedigree alone and predict he’d be equally likely to excel at jumping as he would at dressage. Perhaps, as Schneider indicated, this

is why the sport-horse enthusiast

must consider pedigree, but only after gaits and the horse’s external and internal proclivities.

What’s in a Name?

Take a close look at the pedigree of Showtime (or any other registered Hanoverian) and you’ll notice that there seems to be a pattern to the names on the family tree. Hugh Bellis-Jones, executive director of the American Hanoverian Society (AHS), took the time to explain naming conventions for Hanoverian horses, which apply to horses registered with Germany’s Hannoveraner Verband as well as those registered with AHS’s reciprocal studbook. The AHS is responsible for issuing papers to all Hanoverians born in the U.S., so as its executive director for 22 years, Bellis-Jones has overseen the naming of thousands of Hanoverian horses.

According to Bellis-Jones, “As far as naming protocols go, a most important tradition is that Hanoverian horses are required to have a name that begins with the same letter as the sire. The naming process doesn’t identify female families; it identifies sire lines. So descendants of Donnerhall will have a D name, while descendants of Escudo will have an E name. In practice, owners can call the horse whatever they like, show it under whatever name they like, but if they want to register the horse, it must follow this protocol.” Bellis-Jones explains there can be more than one sire line that begins with a certain letter (D is a good example), so looking at the first letter of a horse’s name might give one a hint as to his breeding but does not absolutely indicate his lineage. Bellis-Jones also points out one exception to this rule: “Offspring of certain W-line stallions whose pedigrees contain Feiner Kerl and Ferdinand must be named beginning with the letter F. The intention is to distinguish and indicate the importance of these foundation sires in this particular sire line.”

Bellis-Jones explains that the vast majority of U.S.-bred Hanoverians are named as foals at the time of registration, which is what the registry encourages, while some are named as yearlings. Mares and stallions who come into the studbook from an outside registry (e.g., a Thoroughbred) must already be named at the time they are approved as breeding stock. Any offspring must then have a name that begins with the same letter as the approved sire. (We can see an example of this in Showtime’s pedigree: his great-great grandsire, Sacramento Song, was a Jockey Club-registered Thoroughbred, but the registered Hanoverians that descend from him all have names that begin with S, hence Showtime). Bellis-Jones says that the name of a registered Hanoverian can be changed at any time, with one important exception: Once a stallion or mare has gone through studbook approval, the name cannot be changed.

According to Bellis-Jones, additional rules govern Hanoverian naming traditions. Once a horse is an approved stallion, any full brothers of that stallion who subsequently become approved must be given the same name but with a number added. (Again, to take an example from Showtime’s pedigree, we see that he’s descended from Pik Bube I, the legendary stallion bred by Günter Pape in 1973. This horse should not be confused with full brother, Pik Bube II, the stallion bred by Günter Pape in 1975 who would go on to stand at the State Stud at Celle, Germany, and become a prolific sire in his own right.)

In addition, names are restricted to 20 characters, including letters, punctuation marks and numerals. The AHS does not permit names to be duplicated, but it does allow horses to have the same name but be given a number (see Pik Bube example above) or for initials to be added after the name. This differs from the Hannoveraner Verband, which allows names to be duplicated exactly and which Bellis-Jones says is actually a common practice in Germany. (He gives the example that the AHS has on record 25 mares imported from Germany and all registered under an identical name: “Wanda.”)

Part practical strategy and part time-honored tradition, naming practices are highly regulated. But, Bellis-Jones cautions, these rules apply only to Hanoverians. He explains that naming rules and traditions vary widely among warmblood registries—Trakehners, for example, take their first initial from the dam line.