The 2013 Dressage Summit, in Wellington, Florida, brought together three European dressage masters—Walter Zettl, Christoph Hess and Charles de Kunffy—who defined the term “classical dressage” by threading natural horsemanship throughout their presentations. Also on the schedule were natural horsemanship experts Linda and Pat Parelli, who shared the key points of the topic, and former Grand Prix dressage judge Colleen Kelly, who gave a biomechanics lecture tying classical dressage and natural horsemanship together.

During the event, the European dressage masters explained to the audience what classical training means: first, training without force; second, showing a visible harmony between horse and rider; and third, having a relaxed supple horse. The message was clear: Whether a rider is in pursuit of international dressage competition or recreational riding, he or she must honor the soul and spirit of the horse.

Zettl shared his philosophy from a lifetime of experience teaching riders the art of dressage. “The horse will do anything for you. It’s a partnership, a sort of marriage,” he said,”We are always in a hurry. When we ride the horses open-mouthed, we are cheating ourselves. We must try to keep the sensitivity to the leg, to the bend. The horse must be relaxed and seek the hand. The contact must be forward, not backward. Contact is through the whole horse.”

When asked what has changed over the years in the sport, Zettl replied, “There is no difference in training, but there is a change in the type of horse—the breeding. After 1945, we only had horses that were left over from the war. So we really had to ride classically. I had the best trainer ever because he never lost patience. He said it’s never the mistake of the horse. He made us ask ourselves, What did I do wrong? That is why I came into horses the right way with classical training. Today, many times, riders’ horses lose their expression and the nice gaits given to them by nature.”

Zettl said that all riders, especially Grand Prix riders, must go back to the basics and make sure the foundation is solid. “We can’t cheat by taking shortcuts. For example, trot–walk transitions help keep the engagement and are the future of piaffe–passage transitions.” Zettl emphasized building a partnership. The training begins in the stable, building trust through patience.

De Kunffy spoke about classical dressage as a horseman who was born and raised in Hungary and who began riding with masters educated during the golden age of European equitation (1900–1945). As an acclaimed dressage judge, trainer and author who has contributed substantially to the popularity of classical horsemanship, he had much to share.

“It’s not enough for the rider to sit on a horse,” de Kunffy told the group. “The rider must sit inside the horse’s motion not behind it.” He said the rider works up and down from the seat bones. Having them up requires a tall body, a straight wrist to the elbow, a straight spine and the whole rib cage has to be up. Seat bones that are down go from the seat to the heels, with the proper leg position and correct stirrup length.

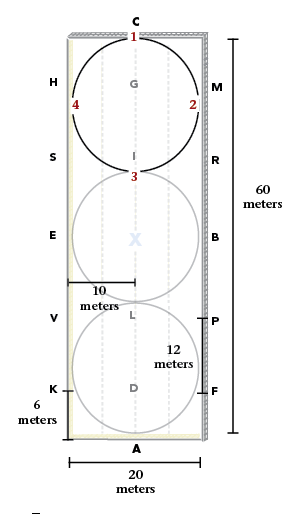

“There are three circles,” he continued. “First, the leg must rotate forward on into the saddle. Second, the foot must be 90 degrees but it can move in a circle. Third, the seat bones must be weighted down, but may also influence the horse. That way the lumbar region can move.” De Kunffy was an expert in getting each rider to balance the horse between the aids.

Hess defined classical dressage as “riding the Scale of Training [rhythm , relaxation, contact, impulsion, straightness, collection].” He added that it is, “alive and well, it’s traditional dressage.” As a Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) “I” judge in both dressage and eventing as well as the current head of the Personal Members Department at the German National Federation, equivalent to the U.S. Equestrian Federation (USEF), Hess has been actively involved in the education of equestrian judges and instructors worldwide.

He taught Mette Larsen, an adult amateur who rode Ulivi, a 12-year-old Danish Warmblood. He stated, “One has to ask when starting the coaching, ‘Where are the problems? What are the challenges?’ This gives me a true chance to make the horse better and obedient to help the rider become a good partner, a positive cooperation, a good spirit to the riding.”

Hess explained how to solve problems. “If something is not working, it’s better to take a step back, make it positive, then go forward in the training again. Every day is a conversation with your horse. You have to listen to and communicate with the horse. It’s natural horsemanship to never pull on the reins, but instead to use the seat. Never fight with your horse. Just go forward and start again.”

Larsen’s horse was tense and looking around, so Hess had her do leg-yielding exercises to relax. “It helps the horse become supple and obedient. Many riders do not go back to the leg yield when the horse gets tense. They think the movement is too basic, but it’s the best way.” He explained that the movements help improve the gaits. “Many people only have in their mind to ride the movements for the next competition. The classical training way is to use the movements to improve relaxation and the gaits.” He reminded the spectators to compare the Training Scale to the colors in a rainbow, one color melding into the next. “All the dressage movements are natural for the horse.”

An inspiring Paralympic rider for Canada (trained by the Parellis), Lauren Barwick captured the hearts of the crowd by riding her horse, Off To Paris, in a beautifully choreographed musical freestyle. Barwick, who is paralyzed below the waist, has participated in three Paralympic Games and continues to show in able-bodied international competition. Without the use of her legs, Barwick was able to demonstrate the balance Hess was talking about during a freestyle.

Hess told the audience, “In competition, we often see horses that are not properly relaxed. The rider is able to control tension, but that is not the way of classical training. We have to learn to think like a horse to understand why he reacts. Lauren is the best example of this. She is truly remarkable.”

To conclude Hess said, “Many people in my country learn a lot of skills so they can ride the movements for competitions, but they don’t have enough feeling for the horse. It may be a problem of our time that with so many distractions like computers and TVs we are losing the time needed for the horse. I hope to go back to Germany and introduce more natural horsemanship to encourage riders to learn from this [groundwork and communication skills]. For the next generation, classical training is not just for riding in a 20-by-60-meter arena with letters. It’s for cross country, for jumping fences, everything. This is written in the book Principles of Riding. Each generation, the book is rewritten to bring more feeling and sensitivity needed for the horse.”

Hess continued, saying that even some top international riders do not have enough patience, and we must look at our own personality for improvement. “Then every day you will have natural horsemanship under you.”

Watching three top dressage masters in the intimate setting of the Global Dressage Festival showgrounds gave everyone a clear view of the thousand-year-old classical dressage principles and how they can work with the newer natural-horsemanship ideals. Zettl said it best: “We have to thank Linda and Pat Parelli for bringing us together.”