Our love of horses touches our lives in so many ways. We all can share endless stories of feeling close to the clouds in happiness or being taken down to the valley of the biggest heartache. Even if you are a professional, sometimes a horse crosses your path and touches you like no other. This is the story of a special horse like that—the horse love of my life, Roulette.

A Foal is Born

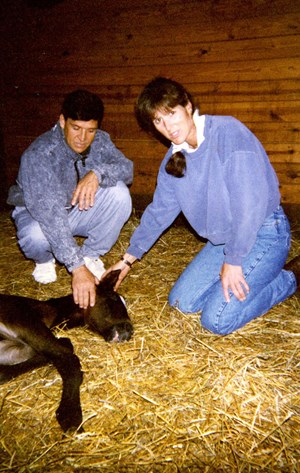

Since the early 1980s, I had been working for Gene Freeze at his First Choice Farm in Maryland. At that time, he was one of the biggest U.S. importers of warmbloods. One of them was a beautiful Hanoverian mare named Parade. She was by Pik Senior, an old Hanoverian bloodline. She was bred to Bonjour, a Selle Francais, and the result was a pretty mare, Beaujolais. In time, we bred Beaujolais to Dutch Rampal, and on May 8, 1996, Roulette was born.

I got to the barn just in time to see him take his first wobbly steps. I had hurt my back badly and wasn’t sure I could go on with my career. Just seeing that foal gave me hope when I needed it most on that beautiful spring day. It was a perfect moment in life.

Roulette turned out to be quite a spitfire. Two grown men had to hold him, even after sedation, so I could clip his ears for the foal inspection where he was awarded Premium Foal status. He grew up in the neighbor’s field in a herd of other youngsters. Gene and I talked about bringing him home to get him started, but there never seemed to be room in the barn. Finally, we had an open stall and Roulette moved in as he was turning 4.

Training Begins

It turned out that Roulette was terrified of a person on his back. Running out of ideas, I called a local cowboy, Roddy Strang, who offered to take him on. After just four weeks, Roddy performed a miracle—Roulette could be ridden, more or less, in all three gaits. That left a big impression on me. I realized how much we can learn from all good horsemen.

Roulette still had many fears. Simple changes in the footing, such as tire tracks, could be a serious problem, never mind puddles. People standing on the sidelines were definitely not to be trusted, and other horses coming at us were a major challenge. He never reared or bucked to try to get rid of me. He would just jump to the side or run like a good old flight animal.

Because he had similar fears in the barn, I got into the habit of doing almost everything around him myself. Tightening the girth was always a delicate task. I am a groom at heart, and he enjoyed his currying immensely, so much, in fact, that he started calling for me in the afternoons when he thought it was his time. His stall was in the center of the barn where he could observe everything, and he started following me everywhere with his eyes. We were becoming a team with a special partnership.

Under saddle, Roulette was sensitive to the aids, but it was hard to get him to overcome his tension. He would easily just run away from my leg a little and not reach into the bridle enough. So it was hard to honestly connect him from back to front. I had to be creative to teach him to canter and ended up teaching it out of the walk so he had a better chance for balance. It was obvious that he would not be going to horse shows anytime soon, which clearly would not have been safe for me or others. Gene came to the barn to help me, and Roulette made slow but continuous progress.

In 2003, Roulette was 7 years old and working at Third level when I thought he might be on the aids enough for an outing. I chose a symposium in Virginia with a former director of the German Riding School, Michael Rush. I knew him and felt comfortable with that exposure. I was proud of how Roulette handled himself and surprised at how calm he was stabling away from home. That was the green light for our first show season.

We won some classes, but one of my biggest challenges remained: to keep his back working. He would feel full of power but hold his back right behind the saddle. It also made the extended walk very difficult. The warm-up remained a nightmare since he was still worried about other horses and people on the sidelines. True preparation for the test was mostly impossible.

Gene was helping me often, and we took lots of video to help me recognize and analyze how I had to improve to help Roulette. For a better connection through his back, we used endless transitions, focusing on lateral work so he would start to lift and step farther under his center of gravity. Gene kept insisting on straightness in all turns to achieve a true bend with the horse staying balanced and upright. It sounds easy, but what a hard goal to achieve! It was an endless challenge to make him reach into the bridle so his neck would stay long enough in the collection—the only way for him to use his back. But things did improve, and the following year we finished by winning the annual Bengt Ljungquist Memorial (BLM) Championship at Fourth Level.

Through the first couple of years, we struggled with many different problems including shipping. Once at a show, he was calm in the stall but a terror while walking in-hand. I saw more of his navel than I’d like to admit and probably could have used some more help from my cowboy friend. I used pressure points in his neck to teach him to release his neck when he got excited and raised it. With an arched and more relaxed neck, his mind stayed more with me. It definitely helped him to be walked a lot and visit all the flowerpots and judge’s booths. He needed to see everything. Slowly, he got more trusting with horse and human in the warm-up area. I groomed, braided and got him ready mostly by myself in the first years.

We hit a milestone in 2005 when we qualified for the Prix St. Georges (PSG) at the famous show Dressage at Devon in Pennsylvania. I realized how much Roulette’s confidence and trust had grown by the way he handled the crowded warm-up areas there. We won a ribbon and, to my total surprise, he was a rock star in the awards ceremony with a ribbon flapping on his bridle and horses galloping. One just never knows.

By 2006, Roulette was turning 10 and we started showing at Intermediaire II. I still had trouble getting him collected enough for piaffe on the spot, but many things had improved. Then Roulette sustained an injury and was lame in the right hind. Instead of going to Devon, we took him for a nuclear scan on the recommendation of my veterinarian, Dr. Roger Scullin. There was some inflammation in the side of his croup, which we were able to treat through targeted injections.

Ready for Grand Prix

By the spring of 2007, when the first show came around, I thought we just might be ready for Grand Prix. This was emotionally a big deal. My “sunshine horse,” as I used to call him, had matured into a Grand Prix horse, despite the rocky road. Few riders have the chance to take a horse from a foal to the Grand Prix ring. It is an incredible journey and only possible with the unwavering support of the owner. Gene never considered selling Roulette, even though it would have been financially the right thing to do. He spent endless hours coaching us and, as the owner of County Saddlery, he made several saddles for Roulette, who was a saddle-fitter’s nightmare. Roulette repaid Gene’s kindness by nickering loudly when he drove up to the barn.

At our first show, we won Intermediaire II and Grand Prix with 70-percent scores. Roulette continued to win at national shows, ending up in the top 10 Grand Prix horses in the country that year. But most rewarding was that his score average had gone up as we went through the levels. Many of my fellow competitors and trainers complimented Roulette on how the training had made him more beautiful.

In the summer he developed a bladder stone that had to be dealt with instead of going to Devon. The following spring he had a terrible bladder infection that had to be treated with expensive intravenous antibiotics for at least 10 weeks. The bacteria were so strong I feared it might kill him. In the meantime, he acted totally normal, and I continued training conservatively. It was a huge relief when he was finally free from infection.

At Devon, in the fall of 2008, the atmosphere was amazing. The floodlights and close-up crowds gave the most seasoned horses problems, but Roulette gave me the best feeling ever. Just as we were ready to turn down the centerline, someone in the crowd stepped on a plastic cup right next to us, which sounded like a gunshot. Roulette jumped to the side, but after one small circle, he was right back with me. His confidence and pride were thrilling—the best high you can get from riding. He finally put his tension into positive power. It was a perfect moment in life that I will never forget. Even with a few mistakes and some forward creeping in piaffe, Roulette got great applause from the crowd as we walked out on a long rein, and he seemed to know it was for him. He had come a long way.

A Twist in the Tale

Show season 2009 started to roll around. Roulette was now a seasoned competitor at the Grand Prix level. In the last couple of years he had overcome his difficulties and fears and several severe health problems. And we had developed a personal connection like nothing I had ever had with another horse. At our first outing in North Carolina he won the GP freestyle with over 70 percent, and I was looking forward to our first CDI in Chicago. It took us two days to get there and when we arrived, it was pouring rain. We unloaded into a crowded stabling tent, where the aisles were narrow and, of course, everyone had things everywhere, not Roulette’s favorite situation.

The day of the jog, the weather was beautiful. In the warm-up, Roulette was using himself better than ever. Gene, who was coaching us, remarked how good he looked and how much the basic quality of his gaits had improved. The day of the Grand Prix we were back in a downpour. Roulette was tense in his stall when we were tacking up. All his life we struggled with girthing. I decided to try tightening the girth while walking down the aisle so the saddle would not get totally wet.

Roulette walked out, and as I tried to tighten the girth, he spooked, rearing straight up and flipping over backward, his neck kinked against the stall wall. Thankfully, nobody was hurt. He got up and we proceeded outside to jog him quickly in-hand. He looked sound, and there was not much time to make a decision, so I mounted and continued to the warm-up. Two days later he did not feel right for the freestyle.

Back home, when I rode him lightly, I felt he had no power to push, so the next shows were cancelled. With no true improvement, we took him for a nuclear scan and other diagnostics. I was told that Roulette exhibited neurological signs. I was floored and could not believe it; in fact, I told myself that they must have drugged him too heavily for the X-rays. We tested him immediately for EPM, which came back negative. All summer, I continued to work Roulette lightly since his unevenness was barely visible, but the lack of propulsive power was concerning.

We tried to turn him out as much as possible, but he was one of those unsettled horses, wanting to run the first couple of moments, and sometimes he tried to pull away. One day he slipped, falling on his side. After that, his lameness seemed more pronounced, and we decided to hand-walk him only. In October he became extremely neurological almost overnight. He was barely able to stand and could not safely walk out of his stall. Worrying that he might fall or lie down and not be able to get up, my assistant, Corinne, stayed with him several nights. I hope I thanked her enough. We celebrated the first fresh manure on his blanket as a sign that he had been able to rest lying down and get up again.

The X-rays showed some changes but, as we all have experienced so often, nothing conclusive. My heart was breaking. What chance did he have? Would he still be around at Christmas? He still nickered for me to come and groom him, and I would try to pick his feet and use that as a measure of his stability. Finally, it was possible again to hand-walk him, but he was very unstable and not able to pick up a stride of trot. You could see his muscle disappear and without stimulation it could not get better, so we walked him as much as possible.

On Thanksgiving Day I got him out of his stall and walked him on a longe line. Suddenly, he broke into a jig and I burst into tears and hugged him. There was my first little ray of hope. There had been a lot of serious thoughts in my head about how long it was fair to let a horse go on like this. But he had not seemed in pain, only a little depressed. Now we started to increase our efforts.

His first attempts to canter were scary, but that improved as well. As he got better, he walked over poles and we added walking downhill, which is difficult for a horse with a neurological problem. Corinne spent endless hours working him from the ground to help him find his body again. His first antics scared me, but when I saw him land back on four feet, they made me smile. He was starting to feel himself again.

A Bittersweet Decision

A year and a half later, he was under saddle again in all three gaits, and I dared to look to the future. If he was not fit enough for high-level Grand Prix, I thought maybe Corinne could show him and earn her U.S. Dressage Federation medals. Then one day when I was helping her with walk–canter transitions, he lost his coordination and almost went down. He was so uncoordinated that it took hours to get him into his stall. I was devastated, and we all came to the consensus that his only chance for a life worth living (and to ever get better) was to be turned out. I knew he needed a field-board situation to stay outside all the time. I asked my dear friends Linda and Joe Denniston if they might have room at their farm. Linda is someone I trust and she was, as always, willing to help.

I was relieved to have found a situation, but I had big concerns about the transition. Would he run and break a leg? Would he pace the fence line lathered in sweat? I realized it was selfish to keep him in a stall without work just so I could see his face every day and hear him call. I would have to take the risk. I decided on the middle of October so the grass would not be too rich and he would have a chance to get used to the environment before the winter. I could not sleep the night before. This would be the day Roulette would leave his stall at First Choice Farm where he had been for 11 years. He would not greet me anymore or request his grooming time. His wonderful eyes that always followed me would not be there. I prayed all would go well.

We were blessed with a beautiful warm fall day with the colors of nature glowing. Linda decided to put him in a huge field with a weanling and yearling filly. As we walked Roulette in the paddock, the babies came running up to him. He greeted them with the most beautiful arched neck and amazing gentleness. I couldn’t believe my eyes. Our high-strung show horse trotted around with the babies, who seemed to be showing him around. His gentleness toward them was precious. He never once panicked or raced. He settled right in as if he had always been there—totally peaceful and serene. I stood there and cried. Going down centerline for a Grand Prix test with him had been an amazing experience, but watching my best friend on the first day of his new life was taking my breath away. It was a wonderful gift after all the worry—another perfect moment in life.

When time allows, I visit Roulette, holding him for the farrier or bringing him treats or a new blanket, and most of all, just to rub the white star on his forehead the way he loves it best. He is always happy to see me, but the look in his eyes shows me how, in his new life, he is complete without me.