Let’s start with a definition of Asymmetry. Very simply, I consider it a lack of balance if the rider’s body is out of position and weight is distributed unevenly. On the straightaway, when something causes the weight distribution to be uneven, the rider’s position will not be evenly balanced or symmetrical. When the rider is not symmetrical on the horse, the horse has to compensate for the extra weight on one side. It’s just like a person carrying a knapsack. If you pack it right, it doesn’t weigh much and it is comfortable to carry. If you pack it wrong, your stride changes.

The minute you pack your body wrong on a horse, his stride changes. But when you correct the asymmetry in your body and make sure your weight is distributed evenly, the horse immediately goes well. He will drop his head, his back will start to come up, and he will show more freedom in his paces. And he’ll probably say to himself “Ohhhh! That feels so much better. Why didn’t she do that a long time ago?”

Usually, most asymmetry is not skeletal. People think it is, but it is rare that the bones are that much out of whack. Asymmetry usually comes from one side of the rider’s body being tighter and stronger than the other side. I’ve had people tell me that they have one leg shorter than the other, but when they have freed the muscular tension and they dismount, they are amazed to find that both feet hit the ground at the same time.

Finding Your Asymmetries

If the weight distribution is even, the rider probably will be symmetrical in the way he or she sits on the horse, but it’s rare to find a rider who is completely even and square. Most people don’t realize that they aren’t symmetrical until someone points it out. Remember that the way we walk or ride is really done out of habit, and a habit feels fine. When you become even and balanced, it usually feels scary for a while because you are used to riding asymmetrically.

Think about your own riding for a minute. Do you ride with one stirrup leather shorter than the other? Does your saddle shift to one side during your ride? Now think about the way your horse goes. Does he seem heavy on one rein? Are his trot lengthenings uneven? Does he trail a foot behind when he halts, instead of standing square? Does he not want to drop his poll or round his back? All of these can be signs that you are not remaining symmetrical in the saddle.

A key question to ask yourself is what are your seat bones doing on your horse’s back? The seat bones are where the majority of your weight connects with the horse. Are they evenly centered over the horse’s spine? Is your spine in line with his? It’s hard to become aware of those changes on your own, so be sure you have someone on the ground who can help. The ground person should watch you ride away from her at the walk and the trot, and she should look at your spine and hips to see if you shift or lean.

You also will find that your hip joints have to be equally soft or you’re not symmetrical. Your torso has to be stacked directly above your seat bones; you will know you are doing this correctly when your muscles relax and you feel effortlessly balanced. When you have that kind of symmetry, you’ll be able to use your seat and hands more evenly and effectively.

Many people also carry one seat bone farther forward than the other because of muscular tightness in their hip. The difference may be only one-eighth inch but it makes a huge difference to the horse. You might feel you are crooked when you bring the seat bone back to where it should be because you get so used to the way it feels when they are uneven.

Releasing Muscle Tension

Let’s suppose that you have a stronger right leg, as many people do. The right side gets tight and shortens. When you rise to the trot, you will rise over the right foot because that’s the strong leg, so your hips will move to the right as you go up. As you sit down, your hips collapse to the left, which is a stronger movement than the rise on the right side, so the saddle tends to slide to the left. This may seem contrary because you’re putting more weight on the right side, but when you come down, the thrust takes the saddle. You will have been losing the left stirrup through all this because you are putting more weight in the right one. So what you’ve got to do is lengthen your right side and release the muscular tension.

My way to help a rider release muscle tension and gain new awareness on one side of her body is to have her ride with one hand in the air. Try this:

•Put your arm out in front of you with your hand in front of your sternum and the thumb on top.

•Raise your arm straight up in front of you so that it passes close to your ear with the thumb pointed to the back.

•You have a hand up in the air that is free with your fingers pointed toward the sky but not rigid. Think about floating your fingers to the sky and patting the clouds. The movement of the hand with the thumb makes the release greater than if you allow the palm to go forward or out. This will release the side of your body and allow it to lengthen. Do this exercise any time when riding or even while standing on the ground.

If you’ve raised your right arm, your weight goes diagonally through your body into your left seat bone and left foot. Your left seat bone probably hasn’t touched the saddle for a while, and people are surprised to find they suddenly have that seat bone. Now, you have two, even seat bones, which is exciting. If you lose this feeling, you can get it back any time you want by putting your hand up. Eventually, you will be able to do this just by thinking about it.

Becoming Symmetrical

Two important words in my vocabulary are aware and allow. You have to become aware of the changes you need to make, and you have to allow your body to change. If your horse feels tight somewhere, check yourself first. Once you are aware of an asymmetry, then you usually can correct it.

I like people to go through their body piece by piece. Go down through your body and just check things: how’s your jaw, your throat, your shoulders, your elbows, etc. You need to become aware of how your body feels, not try to fix anything at that point. When you just put your awareness on some part, your body can start to release or correct it. So then move on to other things during your riding session and come back later as each part has probably improved. This becomes an automatic checklist.

There is also an exercise that I call “comparable parts.” The part of you that tightens up is what’s going to tighten up on your horse. So if you have a tight hip, your horse is going to be tight in the corresponding hip. The hind leg won’t swing freely. If you have a tight knee, your horse will be tight in the stifle; if you have a tight ankle, you’ll see a tight hock in your horse. If you have a tight throat or shoulder, you’re going to have the same in your horse. If you set your jaw, so will your horse. Think about your body and its comparable part in the horse. If something is going wrong, check yourself first.

Riders need to have a better understanding of their physiology and skeletal anatomy. They usually know more about the horse’s bone structure. Riders don’t take care of their bodies when they get hurt—they just muscle through it. They wouldn’t do that to their horse—they’d take care of the problem.

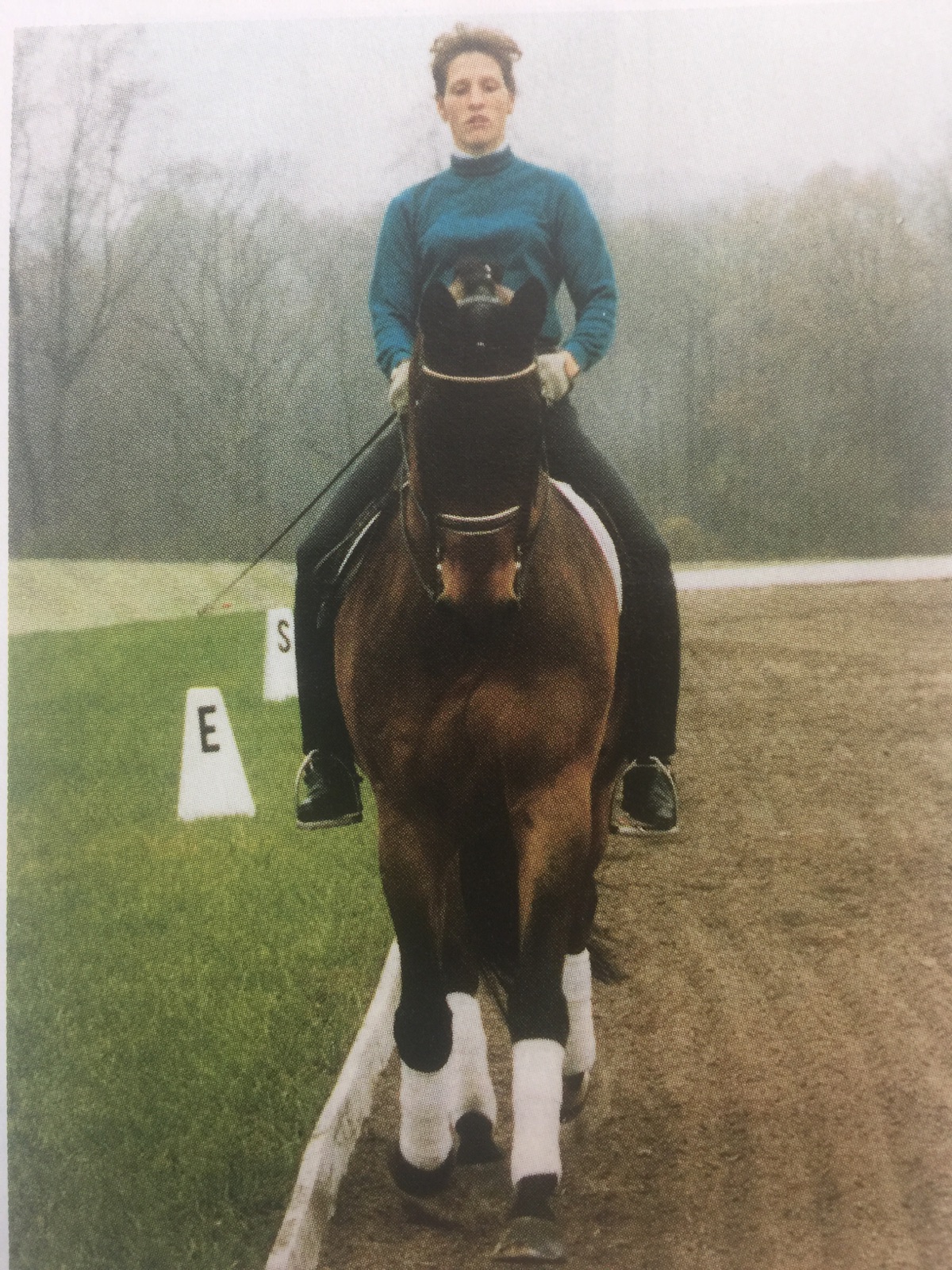

The above photo demonstrates a horse reacting to his rider sitting correctly and symmetrically. Observe how this allows the horse’s movement to be square and free. Compare his head and leg position to the photo below, where our demonstration rider, Felicitas von Neumann-Cosel, is purposefully sitting asymmetrically. Her shoulders, seat and legs are not square. Her right foot is higher than the left and her right shoulder is lowered. Her muscles on the right are tight. The horse must compensate for a crooked rider, and he reacts with his body and brain. His feet are confused and scrambled: the front legs are wide apart and the back legs are crossed. His body is tense and his head is tilted.

Sally Swift is the creator of the concept of Centered Riding® and author of popular book Centered Riding, which has been translated into six languages. Currently, Swift is working on her second book More Centered Riding with publisher Trafalgar Square. She lives in Brattleboro, Vermont.

Freelance writer Anne Millman trained with Sharon and Grant Schneidman and Scott Hassler. She currently manages a neuro-science journal at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

This article first appeared in the June 2000 issue of Dressage Today magazine. Please note that we now require featured riders to wear a helmet.

_____________________________________________________________________

Symmetrical Riding—A Personal View

By François Lemaire de Ruffieu

Q: When did you become aware that symmetry was important in riding?

A: As a young rider in Frnace, I became aware of some problems with my position, which we could call asymmetry. My horses were not going well, and my instructor pointed out to me that it was basically related to my seat. A good seat is the quality the rider must have in order to stay with the horse in all circumstances, no matter what the horse’s reaction is. It’s not made out of strength. It is basically pure balance.

Sally Swift and I both share this philosophy. In her teaching, Sally approaches riding from more of a mental perspective, using great imagery, and I tend to work with the more physical aspects of riding—a great combination.

Q: What is the first thing you do when a horse isn’t going well for you?

A: Automatically, I go through a checklist of my own body. When I am giving a clinic and I hear a rider say “Oh, my horse is leaning on my left hand,” my reaction will always be: “Correct your position.” Probably 90 percent of the time, a horse isn’t going well because the rider is out of position. We have a saying in France that is a horse does not perform well, the rider does not deserve it because the rider is getting in the way. I heard that first as a young rider and then in the Cadre Noir, I heard that all the time.

Q: What happens when a rider is asymmetrical or out of position?

A: If the rider doesn’t correct his posture soon enough, then it becomes a habit with the horse, and the learns to lean on the rider. But the horse is not the one to blame. If you look at horses when they are at play in the pasture, they are absolutely perfect. They stay in balance. Horses become clumsy when we become a deadweight on their backs and get in the way. But, if we learn to do the appropriate gymnastics, prepare ourselves properly and learn how to follow the horse, then we can stay in balance and so will the horse.

Q: How can the rider prepare himself on the ground to be a better rider?

A: In any sport, the participant needs fitness and coordination. In the United States, men and women will always prepare their bodies by stretching before their chosen sport—except for riding. What’s wrong with this picture? The Greeks 6,000 years ago understood that the first thing with horses is that you have to learn to stay on them. And the only way to do that is to stretch and prepare your body so that you can follow the horse no matter what he does. In Europe, I was trained to do all kinds of stretching before getting on the horse, to make sure that the muscles are flexible so we can follow the horse. The rider should spend a few minutes stretching each muscle group so that backward, forward and side-to-side flexibility is improved. Many riders forget to stretch their ankles, but these are shock absorbers. If you are tight in the ankles, you will get tight in the knees and then in the hips, and you won’t be able to follow with your seat. You can put a brick on the ground and put just your toes on it to stretch the muscles around the ankle, then take the brick away and rotate your ankle to make sure it is supple. Any sort of stretches that make you feel more limber are going to improve your riding.

Photo caption: The above photo demonstrates a horse reacting to his sitting correctly and symmetrically. Observe how this allows the horse’s movement to be square and free. Compare his head and leg position to the photo at right, where our demonstration rider, Felicitas von Neumann-Cosel, is purposefully sitting asymmetrically. Her shoulders, seat and legs are not square. Her right foot is higher than the left and her right shoulder is lowered. Her muscles on the right are tight. The horse must compensate for a crooked rider, and he reacts with his body and brain. His feet are confused and scrambled: the front legs are wide apart and the back legs are crossed. His body is tense and his head is tilted.

François Lemaire de Ruffieu received his formal training at the Cadre Noir in Saumur, France. He is the author of The Handbook of Riding Essentials and The Handbook of Jumping Essentials. The is an active clinician in the United States and abroad, with students competing at the Grand Prix level in both dressage and jumping. He became interested in Centered Riding and has collaborated with Sally Swift since 1989. He teaches and trains in Wellington, Florida.