Almost everyone has come across these comments from judges or trainers: “Too much bend in the neck.” “Not enough bend in the body.” “Shoulders are falling out or in.” “Loss of balance in the corner.” “Need more angle or too much angle.”

The common ingredient that would help solve these problems is the understanding of how to develop a horse who can bend equally in both directions without losing self-carriage and lightness, in order to be able to maintain balance through a turn or lateral movement.

Pics of You

A horse who is bending properly has to flex laterally in the poll and neck while keeping the neck centered between both shoulders. He has to pick up his rib cage on the inside without bulging too far out to the outside. His jaw, shoulders and hips will align with the line of travel, almost like a little shoulder-in and haunches-in at the same time. A horse who is uniformly bending gives the appearance of having a curved line throughout his body. The famous sentence by dressage master Gustav Steinbrecht “ride your horse forward and straighten it” relies on the rider’s ability to create relative straightness through curved lines.

(Pics of You)

Framing the Horse in the Bend

The rider must be able to coordinate all her aids to keep the horse balanced between them and to create an honest bend. Control over the rider’s own weight while keeping her legs softly by the horse’s side is a must. She has to be aware of her leg position, with the inside leg supportive by the girth and the outside leg slightly behind the girth to control the rib cage on the outside. The rider’s shoulders have to stay parallel to the horse’s shoulders and the hips parallel to the horse’s hips. To keep her weight in the right direction the rider has to turn from her core to initiate the line of travel for the horse on a bending line or lateral work.

The hands should remain close to the withers to allow the horse to take a connection and to help maintain balance and give lateral flexion in the poll necessary for the bend. The coordination of the rider’s legs and hands are framing the horse.

It is not possible to train a horse to correctly bend without an independent seat and a very good feel for the balance of the horse. The rider has to be aware of where the horse’s shoulders and hips are and evaluate from stride to stride whether every leg of the horse is as evenly weighted as possible, which is a telltale sign of balance.

The rider has to be able to ride simple lines of travel just depending on her weight for steering and her seat for rhythm and tempo with a horse reaching to the bit into a soft contact. This way the horse is challenged to find his own balance. The concept is similar to the idea of being able to ride a bicycle without holding onto the handle bar. This sounds simple but it is a bigger challenge than it appears.

This is very important, since too much rein, particularly on the inside, can invite the horse to lean or lose the alignment. A horse constantly ridden with very heavy contact will start bracing through his under neck or will start depending on the contact like a little old lady pushing on her walker. In both instances the horse will stay down through the withers and not be able to pick up the inside rib cage to bend.

It is fascinating how sensitive horses are to the rider’s weight and it is too often overlooked how many mixed signals horses get from an unbalanced seat. The more willingly the horse follows the weight, the more he can be supported with the framing aids through the turns. Now both calves, placed softly on the horse’s side, can feel if the rib cage needs support on the inside because the horse is starting to lean in, or a little on the outside if the rib cage bulges out too much and the haunches might start to trail. A tight or gripping leg is not able to feel the horse and will cause the horse to tighten his sides and lean against the pressure.

In The Principles of Riding, (the official instruction handbook of the German National Equestrian Federation), there is a classical sentence that says, “there is no bend without flexion, but flexion is possible without bend.” The rider’s inside hand, feeling the corners of the horse’s mouth, asks for lateral flexion in the poll. The horse’s forehead stays in front of the sternum while the flexion creates a concave neck on the inside. The shoulders and the horse’s cheeks turn the same way. It will give the appearance that the inside cheek disappears behind the neck when you look down. The crest of the neck will flip in the direction of bend and the neck bows out on the outside. The rider will have to gently support the horse on the outside to avoid an overbending of the neck but must still allow the bend. Too much tension or an outside rein that is too short, can inhibit the horse’s ability to bend. It is very important that the horse’s ears stay level, as a head tilt would block the energy of the hind leg going through to the bit.

Some horses are very thick in the jowl area and it is necessary that they reach to the rider’s hand to open this angle. Otherwise the horse will be restricted and not physically able to flex laterally, which could be interpreted as resistance.

The challenge for the rider will be to feel the balance in the stride so adjustments can be made in the next stride to maintain balance. Timing of the aids must be in sync with the horse’s rhythm. Particularly the timing of a half-halt needs to be considered. For example, in the rising trot one should think of half-halting on the rise—at the moment the outside foreleg of the horse comes up and the outside hind leg carries the weight. A slight closing of the outside hand while trying to keep the horse in the air a little longer with your core in the rise can help to bring the front leg in the air a little higher while shifting weight back onto the hind leg. In the canter the same should happen when the outside hind leg tracks up and carries the body. Balance is dynamic, changes every stride and requires constant evaluation from the rider.

Thoughts on Symmetry and Geometry

Imagine a horse from a bird’s eye view, bending on a circle or in lateral work with a perfect bend. Now picture an X connecting the horse’s opposite shoulders and hips diagonally. Even when the horse bends or goes laterally, both sides of the X have to stay symmetrically even. If the shoulders or haunches fall out or in, this symmetry would be disturbed.

Take the circle as an example. If the horse’s shoulders fall out, the line from the inside hip, that is subsequently too far to the inside, and the outside shoulder will not create a symmetrical X anymore. This view also shows how in a curved line the shoulders of the horse have to turn a little like the front wheels of a car, and the hips have to turn a little as well. The lateral flexion in the poll creates the same angle in the horse’s cheeks as his shoulders. Unfortunately, bend is more complex than that. Leaning into a turn for example, indicating the bend is not correct, can lead to loss of balance in more ways than just the shoulders or haunches losing alignment.

Imagine a table. You would want all legs to be of equal length so it is level. Compare this to the horse. If he is on the forehand the front legs will feel shorter; if he is leaning in the turn it might feel like the inside front leg is shorter and the outside hind leg longer than the rest. Considering the balance of the level table, the rider must evaluate how to send energy through the horse during every stride so balance can be maintained.

For example, sending energy from the inside hind leg through the outside shoulder through the outside rein can help to keep the inside hind leg from falling in. Simultaneously, thinking of energy coming from the outside hind leg through the outside shoulder to the outside rein can help to keep the horse from falling out through the shoulder or haunches. At the same time the balance must be maintained by recycling this energy back into either hind leg (if one carries less weight, or both ultimately) through half-halts so the weight stays evenly on all four feet. It becomes clear that there is a correlation between balance and the ability to bend that ultimately straightens the horse. Hence straightness comes before collection in the Training Scale.

Walking on a Tight Rope

Illustration by Sandy Rabinowitz

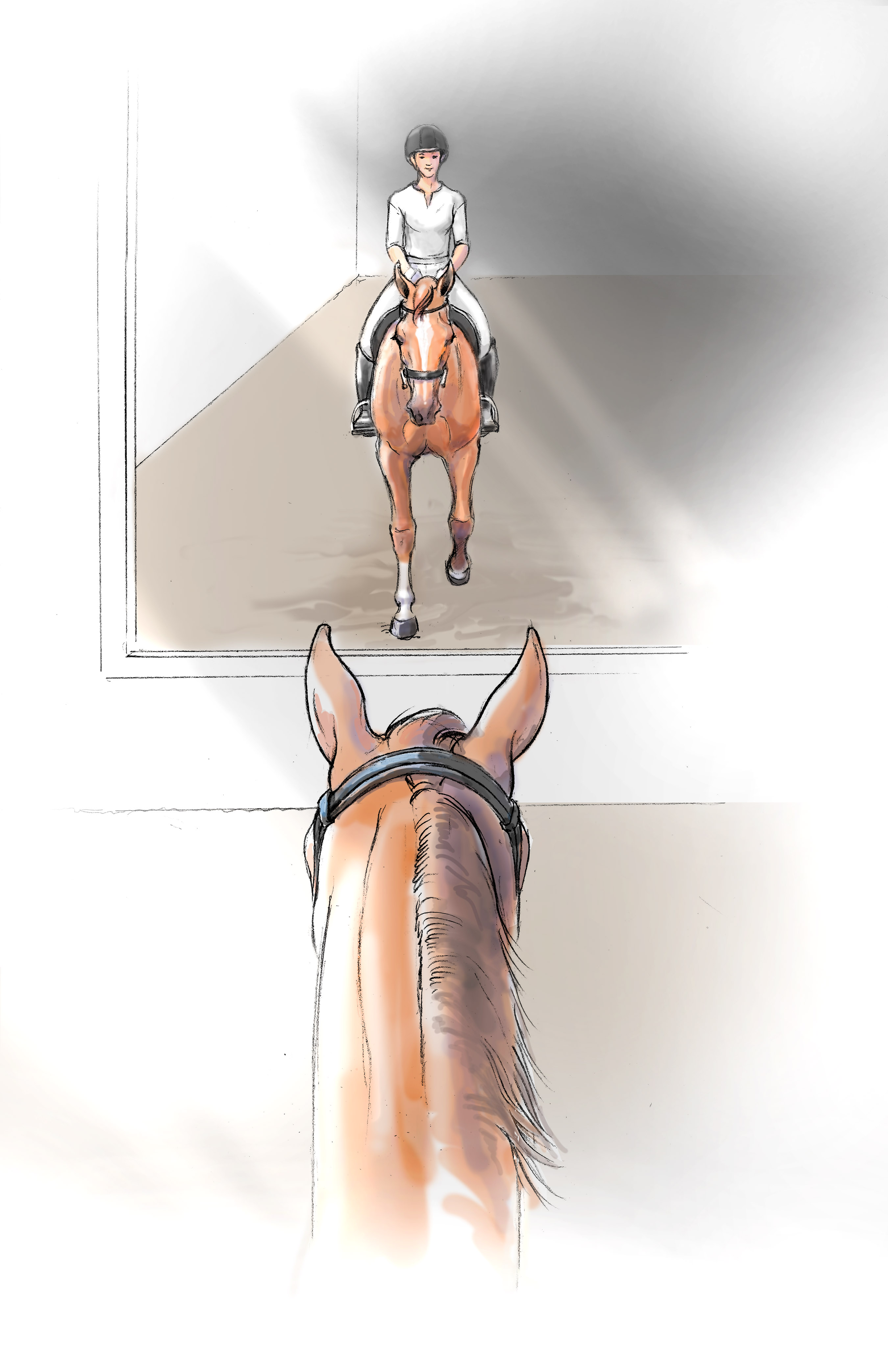

A simple challenge is to ride in the walk down the long side, off the rail, toward a mirror. Imagine the horse is walking on a tightrope. Ideally, looking straight into a mirror you would like to only see the two front legs, since the shoulders should stay directly in front of the haunches. The neck has to stay centered between the shoulders. It is surprising how often the front legs start to step a little to the side as the horse is falling through the shoulder. It feels as if the front end is somewhat unstable. The rider starts to feel the horse’s tendencies and will have to coordinate the aids so the horse can walk that straight line. If legs or hands overcorrect, the horse will get more unstable.

To get back to the original image of the bicycle, in order to follow a straight line there has to be enough forward momentum, as riding the bike very slowly makes it wobbly. The same is true for the horse. In order to walk on that tightrope or balancing beam, the horse has to be going from back to front with enough forward tendencies.

One might think stabilizing through momentum should get easier in the trot then, but that is only true if the horse is tracking straight as we discussed before. If the rider does not have the ability to stabilize the horse, increased speed will actually make the problem worse. Instability often gets very apparent as the horse approaches the corner. In anticipation of the turn, the shoulders might fall in and all of a sudden you see three or four legs. The same misalignment frequently happens out of the corners. If the horse loses his balance before and after the corner, chances are that he was not balanced and bending in the corner.

Gain Control of the Shoulders

For balance we have to be able to control the alignment of the shoulders on a straight line and we have to know how to position them in the line of travel on a curved line. A shallow serpentine is a simple exercise that can be very helpful to learn to control the shoulders.

Try this: Turn on the second track out of the corner and start to ride a shallow serpentine, as if weaving around some imaginary cones. A full-size arena might accommodate two or three loops.

The horse must stay on one track. Turning into the arena the shoulders might fall in or the horse might be reluctant to turn.

Turning back to the track the haunches might fall out, volunteering a leg-yield, or the horse might be reluctant to follow in the new direction. This can give revealing information in which direction the horse is less willing to flex and bend.

Straightening between each turn to set the horse up for the new bend is the link between each turn. The goal is not to make as many loops as possible but to achieve a soft change of bend that feels more equal on both sides. This can be ridden in the walk and trot.

Next, this can be done without changing lateral flexion in the poll on the same line of travel. This also means the rider’s position stays in alignment and proper weight distribution according to the bend. The first part of the loop will be the same, but completing the second part without the change of flexion challenges horse and rider to keep the shoulders on the line of travel and the haunches following—not leading—which would create a leg-yield back in the second half of the loop.

The rider will have to feel what the shoulders and haunches are doing and coordinate the aids so the horse stays on one track. Both hands staying close to the withers can help the shoulders to lead, and the legs have to frame the horse so the haunches are neither falling out nor trailing. This can be done in all three gaits.

The loops can vary in size, steeper if more bend is the goal, or very shallow just to move the shoulders. In the end, it could be as little as a shoulder-in, which would be the first stride into the loop back to straight and back to shoulder-in.

It will depend on the skill of the rider and the individual need of the horse how difficult the exercise should be. The goal is to improve the horse’s suppleness and self-carriage and the fine tuning of the rider’s aids.

Pics of You

Challenging the Bend on the Circle

The next step would be to take the horse on a circle and develop a shoulder-in. The biggest pitfalls here will be a neck pulled too much to the inside, while haunches are falling out in one direction and not enough bend in the rib cage the other way. This is very typical for the horse’s natural crookedness, which we always try to overcome.

Pics of You

Pics of You

Again, the rider will be challenged to feel where the shoulders and haunches are, with the goal to develop the shoulder-in on three tracks with soft lateral flexion in the poll and a giving rib cage around the inside leg.

Keeping the bend and flexion that was created through the shoulder-in, now the rider can develop a haunches-in by taking the shoulders further out of the circle. Both hands by the withers and the inside leg will help to move the forehand of the horse further out to create a three-track haunches-in. Sometimes I encourage my students to think they are taking the withers out of the circle. The outside aids help to keep the haunches in the line of travel. Remember, we are taking the shoulders out, not the haunches in.

Developed that way, the horse maintains a wonderful bend around the inside aids and the rider gets a sense of how important the inside aids are when we move the horse in the direction of travel, as is necessary in travers, renvers, half-passes or pirouette.

The play back and forth between shoulder-in and haunches-in should create a better bend by finding the middle between the two. This exercise can be done in all three gaits and can be made as subtle or big as needed and can also be ridden on a straight line. In the walk or canter it can be done on a small circle until the shoulders out/haunches-in ends up a pirouette.

Armed with this feel of creating a bend, straightening the horse through turns and in lateral work should get much easier. Now when haunches are drifting out in the corner or small circle, the thought could be to take the shoulders more out in front of the haunches. The bend will keep the horse from leaning. The shoulders will not fall in or out if the bend is maintained evenly. If the haunches are leading in a half-pass, it should now be possible to bring the shoulders of the horse along. Should the horse spin in a pirouette it will be easier to regain balance and control of the turn by working on the bend in the pirouette and putting the weight back on the outside hind leg, just to give a few examples.

As a young girl, I read how to put the shoulders of the horse in front of the haunches in Steinbrecht’s Gymnasium of the Horse. At the time it was a mystery to me. Discovering what it means and implementing it has been one of the most important pieces to the endless puzzle of training the horse.

Felicitas von Neumann-Cosel is an international Grand Prix competitor and trainer, and has been located at First Choice Farm in Woodbine, Maryland, for 35 years. Growing up in Germany she chose the route of professional trainer and passed her German Federation Master Exam with the highest score at the time. Besides winning many championships she is known for developing her horses as beautiful athletes, improving their gaits and physique as they move up the levels. Her creative approach to teaching the horse and rider makes her a very popular teacher.