Sixty years ago Lis Hartel from Denmark became the first woman to win an Olympic medal in dressage. More remarkable was that she was paralyzed below the knees and rode her horse mostly by shifting her weight. Since that time, competitive riding by the disabled has become increasingly popular, with the quality of the horses they ride growing all the time. What remains consistent is that Paralympians repeatedly prove it is possible to ride a horse with the lightest of aids.

Germany’s double Paralympic champion (Grade III) Hanne Brenner was an upper-level eventer until her rotational fall in a three-day event at Luhmühlen, Germany, in the 1980s. Having been left with an incomplete paraplegia and similar handicaps to Hartel, she turned to dressage and not only became one of Germany’s Para-Dressage stars, but won her first S-level (Fourth Level to FEI) class against renowned able-bodied riders.

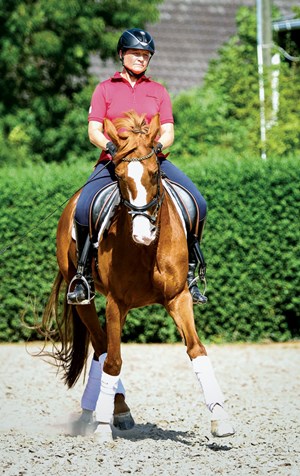

In the following article, Brenner explains how she compensates for her handicap and how she rides her horses with the lightest of aids. She highlights a proper warm-up phase and a well-trained horse as the indispensable basis for good communication.

A Typical Training Session

People often ask me how my 20-year-old Hanoverian mare, Women

of the World (aka Ollie), is able to perform up to S-level with me giving her different support from that of an able-bodied rider. In principle, I do not give aids much differently, but due to my handicap I cannot work with strength. To compensate for this, it is of utmost importance that I focus on my horse’s submissiveness and smoothness—the goal of my training sessions. In this article I describe a typical session from which every rider can benefit, followed by a discussion of how I get my horses used to very subtle aids.

Each training session starts with 30 minutes of walk. This may sound very prolonged, but it really helps the horses to relax. During this walk phase, I use the last 10 minutes to ride the horse onto the bit and ask for the first lateral movements. Then I switch to some rising trot. Because this is very exhausting for me, I usually pick up canter soon after. I still consider this the warm-up phase, so my aim is to bring my horse’s hind legs increasingly under her center of gravity. For this, I ask my horse to lengthen and shorten her strides, while riding on circles or voltes.

After a short walk break, my focus is to make my horse more “electric”—in the sense that she reacts quicker and pushes from behind into my hand. Each horse is different, but horses who might not be that sensitive can benefit from you asking them a lot of different things during the working phase—especially in succession, which they don’t expect. This tactic keeps them attentive and listening to you. For example, you can ride:

• transitions from trot to walk or from trot to canter.

• transitions within a pace on straight or curved lines.

• leg-yielding through the diagonal with shoulder-fore on the long side.

• riding corners precisely as quarter voltes.

When I have the feeling that my horse is really engaged from behind and listening to me, the warm-up was successful and I can start working on a special movement that I want to practice. It is a severe mistake for any rider to ask this before the horse is ready within a training session. An able-bodied rider might be able to ask for a movement through strength, but I depend on my mare being really ready for it, and this is the precondition to honest communication with the horse, which should be the utmost aim for every rider.

There are days in which a horse might not come any further than the warm-up phase, but this does not necessarily represent a setback. Horses are living things and are not the same every day. It is only a setback if you ignore the failed warm-up and still switch to the working phase. Then you can only ride with pressure and strength, which is an uncomfortable feeling for both horse and rider.

How to Get a Horse Used To Subtler Aids

Shoulder-in often appears to be a cure-all in dressage. In fact, it is a very important exercise that I regularly use in my training sessions to keep the straightness of my horse and make her move more smoothly. Riding shoulder-in requires certain aids from the rider that are not easy for me to apply due to my handicap. The posterior musculature of my legs is weak on both sides, so I cannot really use a coffering—give-and-take—outside leg the usual way. If I try to, it affects my overall balance badly.

Due to this, I am allowed to use two long whips, but Ollie does not like whips, so I usually use only one, if ever. For example, before our gold medal at the 2008 Paralympics in Hong Kong, I threw it away because I felt her getting tense, and it still worked out.

To ride the shoulder-in, I use the aids everybody does, but in a much gentler way: I position my outside calf behind the girth, but this also means my whole balance changes and makes my seat a bit unquiet for a moment. Why does my mare still understand me? First, she is prepared the way I described earlier, which means she is really submissive and listening to me. Second, my Danish trainer, Dorte Christensen, also rides all my horses. Dorte gives the same traditional aids with the usual intensity of strength, but we gradually reduce that in the course of our training.

So, when I sit on my horses they usually know what I am asking of them, even though there is less strength. They are trained to be sensitive and attentive from just a touch of the aid from my trainer. Then they still react the same way with me aboard. This fact truly shows that horses can be trained to react to subtler aids than riders usually give. The aids need to be correct after the classical doctrine, but the intensity is something that can be trained.

No doubt there are horses more suited to the aim of riding with subtle aids than others, but in the end this doesn’t matter. Every horse’s reactions to the rider’s aids can be improved on the basis of a proper warm-up and consequent conditioning, but not every horse is later ridden so sensitively. If you are an able-bodied rider, just try to progressively reduce the strength of your aid.

First, make sure that your horse is submissive and listening to you. You need to have your horse correctly between your legs and hands. A good preparation exercise is shoulder-fore, as the aids from the rider are very similar to that of shoulder-in. However, this movement requires less collection and bending from the horse and might be easier for many to start with. You can ride shoulder-fore with a volte on a long side of the arena, as then you already have the correct bend. Keep the horse at a wall so she can “lean” on it, which makes everything easier.

When you have finished the volte, you push the horse with your inner leg against your outside rein, which activates her inner hind leg to step under more. Your outside rein helps control her outer shoulder, whereas your inside rein brings her forehand in and determines the bend, which, at the shoulder-fore, should be only slightly visible.

The aids for the shoulder-in are almost similar, with the difference that the bend and angle from the wall of the arena are now bigger. The rider’s inner leg is at its usual position at the girth, with the horse bending around it, and the rider’s outside leg is positioned a bit behind the girth to push the horse forward and keep her hind legs active.

Take into account that if you want to reduce the strength of the aid you have to expect that during the first sessions the horse will probably lose some of the impulsion you created through your seat. As a consequence, you should be content with a few steps of shoulder-fore or -in and finish the exercise before the horse needs a stronger aid again to keep going. It is of paramount importance that all features of a good shoulder-fore or shoulder-in be fulfilled with lighter aids.

It’s useless to lessen the strength of the aid if the horse “dies” under you. So be happy with very few steps at the beginning and understand the whole thing as a process that needs time but leads in the right direction. In the end, you should be able to ride a shoulder-in with your legs neither pressing nor pushing, but giving slight pulses.

It should be encouraging for each of you to know that before my accident I could not imagine riding at such a high level of dressage. It’s one of the fascinating and satisfying aspects of riding: If you think and try the seemingly impossible, it happens one day. You just have to do it!

Women of the World: Para-Dressage’s Equine Heroine

She might barely be 15.3 hands and 20 years old, but Women of the World (aka Ollie) is one of Para-Dressage’s all-time greats. This is the eighth consecutive year the Hanoverian mare was nominated to represent Germany at an international Para-Dressage championships, and she has never returned home without a set of medals.

At the 2008 Paralympics in Hong Kong and four years later in London, Ollie won double gold in the individual classes and silver with the German team—the same haul she managed to obtain at the 2010 World Equestrian Games in Kentucky.

The mare and Hanne Brenner found each other back in 2006 when Ollie was already an 11-year-old who knew her job. But the feisty mare who descends from Hanoverian breeding’s finest dressage bloodlines (Walt Disney–Pik Bube I) had survived an episode of laminitis and had been through a few sales stables, so she wasn’t in the best of condition.

Careful feeding management and lots of attention brought the mare back on track, even though a tendon injury in their first year together meant another setback. Never looking back since then, Brenner and the mare became one of the most successful and well-known para pairs in the history of the sport. Contesting Grade III, Brenner also regularly competes Ollie in dressage classes at the M- and S-levels against able-bodied riders. They have won several M-level classes and even an S-class so far.

“She’s the horse of my life,” says Brenner. “Never have I had such a close bond with any other horse. If I could only keep one horse, it would be Ollie.”

Brenner lives with her horses on the yard and sees her mare several times a day. Even at 20, Ollie looks the picture of an equine athlete and is still as motivated as at the beginning of her long career. “We owe this to my trainer Dorte [Christensen],” says Brenner. “Without her dedication, Ollie would not be what she still is.” Brenner admits all of this unselfishly, mentioning that her chestnut “lady in red” absolutely loves going to shows, which are like a party to her.

And Ollie? She knows that she’s the undisputed star of the stable and the center of attention wherever she goes. For Brenner, it is the sweetest success that at this advanced age Ollie is still as keen and enjoying her work as at the beginning of their common story of success.

Hannelore “Hanne” Brenner competed in three-day eventing until a rotational fall in the 1980s left her with an incomplete paraplegia. Brenner restarted riding as a hobby soon after, but it took her a few years to pick it up as a competition sport in the 1990s. Brenner is a multiple World Champion and European Champion and a four-time Paralympic gold medalist in Grade III. Her most successful horse is the Hanoverian mare Women of the World with whom she won individual gold, silver in the freestyle and team bronze at the 2014 World Equestrian Games in Normandy, France. Brenner lives in the south of Germany and has a yard with her trainer, Dorte Christensen.

The Para-Equestrian Grades

Grade IA: Walk only tests

Grade IB: Walk and trot

Grade II: Walk and trot but canter allowed in the Freestyle

Grade III: Walk, trot and canter; shoulder-in is allowed in the normal test, flying canter changes in the freestyle

Grade IV: Walk, trot, canter, canter half-pirouettes, three and four sequence changes and lateral work

What All Able-Bodied Riders Can Learn

By Uta Gräf

For a few years now I have worked as the federal trainer of the Para-Dressage riders of Rhineland-Pfalz, including some of our most successful ones—Dr. Angelika Trabert, Hanne Brenner and Britta Näpel. Six times a year, we meet for a clinic, and I try to support them annually at the big international show at Mannheim and at the German championships.

For me, it is fascinating that most of the para riders really aim for a true harmonious partnership with their horses. In most cases, it just wouldn’t work any other way, as they are often not able to ride with strength or risk a fight with the horse. So I always enjoy watching my students ride with a high degree of harmony.

To have a harmonious partnership also means to try riding with the slightest of aids. What we able-bodied riders hopefully all aim for is a pure necessity for my para riders. They are lacking strength in their legs or might not even have legs, so they need to condition their horses to react sensitively to very light aids. Each time I train my students, they bring home to me that it really does not take much to communicate with a horse. In this, among other ways, they are role models for my own riding and me. We all should make ourselves aware that little impulses are enough to make a horse understand what we want him to do. A harmonious partnership is half the battle, but we can only reach it when we respect the horse, and this means to ride with fine aids.

Uta Gräf is well known for her motivated, relaxed and contentedly working dressage horses. With the licensed Holsteiner stallion Le Noir, she has won more than 25 Grand Prix classes and, in 2011, she placed in the top five at some of the most important European CDIs, including Aachen, earning a place on the German Olympic long list for London 2012. She and her partner, Stefan Schneider, live and train horses at Gut Rothenkircher Hof in Rhineland-Pfalz, Germany.

The Shoulder-in

By Angelika Frömming

The shoulder-in is often described as the “mother of all lateral work.” It is the progression of riding in position and bending and plays a decisive role when improving the straightness and collection of the horse.

In the shoulder-in, the horse is bent opposite to the direction in which he moves. He moves on three tracks with an angle of approximately 30 degrees and only the front legs cross.

The shoulder-in has to be shown in a collected tempo, but this doesn’t mean a slow one. Collection without impulsion and swinging through the back lessens the quality of the movement.

Sometimes one can see passage-like steps in the shoulder-in, which is often a sign of exaggerated collection, a lack of relaxation or even tension. Another problem is the tendency of forced riding. Here, the judge has to decide if it is still expressive collection or a free working trot.

The quality of the contact is of great importance. The horse has to take contact with the outside rein and should not be pulled to the inside. The latter causes a lack of impulsion and crookedness of the neck often accompanied by a tight neck. The horse has to take the contact and has to chew with a closed mouth.

A special problem with the shoulder-in is the introduction and the termination of it. During the introduction, the forehand is led inward (not the hind legs being pushed outward). As a consequence, it is the forehand which is brought back during the termination of each shoulder-in. The hind legs are not allowed to evade sideways.

The shoulder-in is an indispensable exercise for any dressage rider whose aims are collection and straightness, but it is also a tricky one as any mistake mentioned above can cause the loss of its gymnastic effect.