As the old saying goes, “You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression.” This thought is particularly applicable to the way riders begin their musical freestyles. Unlike the rigidity of a regular dressage test, the freestyle gives riders the option to do it their own way, by including music and movements they choose. The question is, how do you make the most effective entrance for that great first impression?

Opinions on that vary among those at the top level of the sport, be they riders, judges or coaches, as one might expect with any personal preference. What they do agree on, however, is the necessity of getting the judges to sit up and take notice when they are dealing with a slew of entries. After all, a freestyle is a statement about what a horse and rider have to say to the crowd and the officials.

“This is show business. You better start with a big entrance and finish with a big ending,” says U.S. Dressage Coach Robert Dover, who, during his competition days, always presented innovative freestyles that had everyone talking. (Remember the one that ended with the extremely appropriate vocal, “That’s all!”?)

You better do something innovative to get Dover’s attention. “There have been times when people walk in, halt and walk off, and I think, ‘Next,’” Dover says with a chuckle. “It’s the same as dancing. If you see ballroom dancers go onto the floor and start walking around for the first minute, you’d get a big hook and take them right off the stage.”

FEI judge Janet Foy agrees. “I’m not a fan of people who walk in. I don’t think that’s very dramatic. Even though it says judging doesn’t start until after the halt, it does count in the impression; it does count as part of the entrance and how you get in and out of the halt.”

Foy advises on the importance of “having an entry that makes the judge sort of sit up, and having some sort of entry music that also makes the judge take notice. Often the entry music is so quiet and soft that I’m always panicked a little bit: Is the system working, is the speaker working?”

The manner in which a competitor enters the arena really depends to a great extent on the horse’s degree of training and reaction to an atmosphere that can be electric. Think of the sizzle in Dressage at Devon’s freestyle night or the buzz at the Thomas & Mack Center for the FEI World Cup Finals. A big entrance there could blow up for a horse that isn’t seasoned enough to handle it.

Know Your Horse

Canada’s Olympic medalist Ashley Holzer says there are times when a rider should be cautious. “Making a big first impression is very important, but I also think if you only go for a major first impression and make a huge mistake, that is a huge risk to take. I tell my students all the time, ‘Yes, it’s lovely to make a wonderful first impression. But it’s really, really bad if you crash and burn right in the beginning.’”

Holzer has had direct experience with that. “I’ve taken horses where I thought, ‘OK, let’s go for it, let’s try this’ maybe a little too early on in their career. You want to make a big splash. I think as athletes, we’re always challenging ourselves; we’re always challenging our horses. I don’t think they’re used to coming into a test a little bit nervous and having a big, strong start and that’s why they get marked so high when it does work well. I think you’re looking at a more experienced horse that comes in and has that big-bang type of effect in the beginning of the freestyle. I can give a little bit of advice to people: If you have a green or younger horse, do not go necessarily for that big-bang effect. If it’s dicey, I would wait a moment or two. Get your points by coming in looking relaxed and composed and like you know how to do your job in giving your horse a confident ride,” Holzer says.

Catherine Haddad Staller also warns about not doing too much with a mount that is new to the game. “If you have a horse that is experienced at Grand Prix freestyle, you can choose your entrance, and you should choose an entrance that highlights your horse’s best skill,” she says. “For instance, if he’s super powerful and rhythmical in passage, you can choose passage as your entrance and enter, halt and start in passage again. Remember, the entrance involves not only entering the arena, halting and saluting, but also continuing on toward the judge. That’s considered your entrance, and there’s a score for that.

“However, when you have a young, inexperienced horse at freestyle, he might hear the music while warming up and there might be some extra excitement, so you have to be very practical and say, ‘What is my most sure entrance?’ A lot of times when I’m training an inexperienced horse, I’ll start the freestyle by cantering in and halting because that’s what I do in every test and it’s routine and familiar to him. Then I try to start with something I know is reliable. If I have a horse that strikes off very well, I’ll add extended trot after that. If I have a horse that’s very unsure of himself, I might trot out of the halt, because that’s what we do in every other test that we show.”

You can enter in any gait you want, Staller points out, which offers an opportunity to play up a horse’s advantages and downplay his disadvantages. The time that she entered in walk was for a purpose. “It was a dramatic effect when I did the gladiator freestyle with Maximus,” she says. “He did not like to halt out of canter or trot. He wouldn’t stand very still. But he would halt out of walk, so I had a technical reason for doing it and an artistic reason for doing it.”

Walk Before You Run

Holzer agrees that as time goes by, there’s an opportunity for a bolder entrance, offering a wider range of choices. “When your horse is more experienced, and you know your horse well, you know your music well, you know your pattern well, change it up and risk a little in the beginning. It’s really the only way you’re going to win. But if you look at some of the most highly scored tests in the world,” she cautions, “they don’t have the most difficult movements right away.”

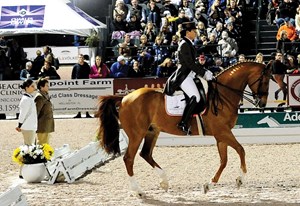

When Holzer won the Dressage at Devon freestyle last year with Tiva Nana, she attracted attention by starting at the walk. It had a dramatic effect the way she did it. “The walk was actually to show the judges that here is a huge atmosphere at a very big event, but I can literally walk in, walk around and come to the center of the ring—most judges know the center of the ring is the most difficult place to do a movement because you don’t have a wall—and start piaffing and piaffe/pirouetting,” Holzer says. “So I was going for drama. If you have a well-educated person, they’re going to know that’s extremely difficult. If your horse is nervous, you’re going to get a jig at the walk. Coming in and doing something like that, which looks easy, is actually extremely difficult, and that’s why [Tiva Nana] gained so many points doing that,” she says about the mare.

Foy offers another thought on the way to get the judge’s attention, and it can be done without putting pressure on the horse. “It’s often a really good time in that entry to use some vocals in your music. I’m not a fan, most judges aren’t, of having vocals throughout the freestyle, but having them thrown in a little bit here and there can really enhance your performance and give you a higher score and some things to interpret.”

It’s vital not to overwhelm the horse at the start of the performance, however, because it can go downhill fast from there. Canadian Jacquie Brooks, known for her powerful freestyles, believes, “You want to highlight your horse in the beginning. You want to start on the right foot. Part of my success with my freestyles is that I really try to tell a story. So I can’t come out huge in the beginning if I want to have that story build. I like to start with something the horse finds easy, so I give him confidence in the beginning of the test. I like to have a couple of builds in the performance. I might do a small build first to something that’s a bit difficult, then make it a little bit easy again and then bring it up again. It depends on your horse.”

With her current top-level mount, D’ Niro, Brooks points out, “I like to start halt, piaffe. He can do it really well. It gives him comfort to stand in that piaffe and look around at his surroundings and take everything in before I actually move off.”

Start Strong, Finish Strong

U.S. Olympic medalist Steffen Peters has shown the world many impressive freestyles with a variety of horses, though what most people will remember is the stunning performance that earned him his second individual bronze medal with Ravel at the 2010 Alltech FEI World Equestrian Games.

“I think the beginning of the freestyle is just as important as the ending, and you should show one of the strong qualities of the horse early on. For Legolas, it’s the piaffe/passage work,” Peters says.

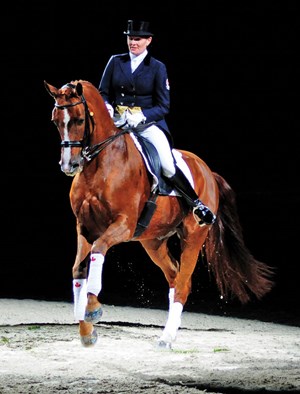

With a younger mount, preparation cannot be rushed. Peters had questions that needed to be answered when he came east from his California home to Florida’s Adequan Global Dressage Festival (AGDF) this winter with the low-mileage, 8-year-old mare, Rosamunde.

“I wanted to find out what she’s like in a big stadium with a lot of people,” he says, noting that he is waiting until he gets home to embark on a freestyle with her. She swept the 3* Grand Prix and Grand Prix Special at AGDF, so it’s likely that she’ll be comfortable when Peters puts her movements to music. But he said he’s taking her progress step by step, making new plans after every show, rather than on a long-range basis.

Lars Petersen is currently the master of the freestyle in the U.S. He started off at the AGDF with three Kür victories in a row. At the Florida 5* fixture, the Olympic, World Championships and World Cup veteran rode Marriett to a score of 79.175, which was close to his personal best. Interestingly, Lars says of the beginning of his freestyles, “I don’t think too much about it. I have done it to trot and canter. If they’re good at passage, I think that’s a good way to do it.”

He has other things on his mind when designing what he will do to come up with a statement in the arena. “When I make a freestyle, I want it to have a pretty high level of difficulty, I want it to be easy to judge and I want happy, fun music,” says Petersen. “Those are the things I always think about. One of my first freestyles when I was at Blue Hors in Denmark was to circus music, and it was fun to see on TV afterward.” He could see the reaction of the crowd and judges as they suddenly brightened up when he rode into the arena to the happy tunes.

Lisa Wilcox, another U.S. Olympic medalist, is “a believer in making a ‘wow’ factor when you enter that arena.” How to do it? “Every horse is a little individual,” she points out. “I enter with a strong passage on one and a strong canter on another. I definitely say wow them in the beginning and wow them at the end.”