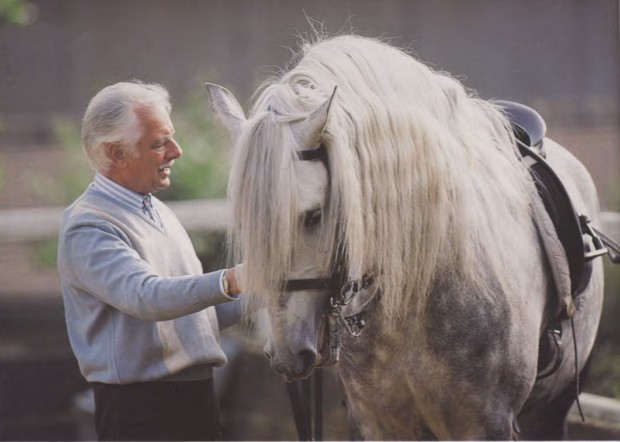

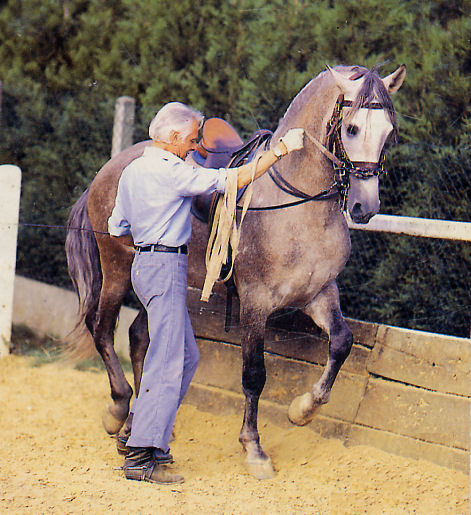

Michel Henriquet, legendary horseman and dressage master, passed away a few short months after my visit to his stables in 2014. His departure was a profound loss for his loved ones and the world of dressage. Through this story, I am honored to be able to share a precious day with Michel and his wife, Catherine Durand Henriquet. I hope that it will touch and inspire the horsemen and -women who would have savored those moments with him as I did.

I am searching for Les Écuries de la Panetière—the training stable of Michel and Catherine Henriquet. At 90 years old, Michel has become one of the great classical masters of our time. His passion for the horses and his quest to develop their friendship, harmony and lightness through dressage has inspired my desire to meet him. An avid student and proponent of the writings of François Robichon de La Guérinière and Antoine de Pluvinel, Michel has become a brilliant trainer and writer himself. He is renowned for his books and for his rapport and 30 years of study with the late Portuguese master Nuno Oliveira. With his wife and primary student, Catherine, Michel has also demonstrated that French classical dressage can shine in the competitive arena. With Michel as her coach, Catherine represented France as an Olympic competitor in 1992. She rode the Lusitano Orphee, the first Iberian ever to compete in an Olympic Games and ranked 26th individually. In 2013, a year before my visit, Catherine had won the French National Championship at Grand Prix.

Tucked in the quiet village of Autouillet, outside of Paris, one would think the illustrious stable would be easy to find. Having successfully navigated my rental car out of Paris, through the pièce-de-résistance of confusing roundabouts, L’Arc de Triomphe, I feel sure I can find the famous stable in this tiny village. Finally, I have to concede to help from Google Earth, which directs me to a plain doorway in a long wall. It doesn’t make sense to me that a stable could be hidden behind a village wall, but I find courage to ring the bell because Les Écuries de la Panetière (the Stables of Panetière), is neatly printed near the door in small letters. A young British working student greets me promptly and ushers me behind the walls, where the realm expands into a beautiful old-world horse farm.

Austere stone buildings frame the happy energy of the horses, dogs and equestrians as they are briskly starting their day. Catherine has been expecting me and she greets me in English. She invites me to watch her teach her first lesson in an old stone-walled, covered riding arena. Dusty trophies line an entire long side of the narrow arena. Catherine directs me to a viewing room at one end so that I can watch her first lesson. Her large dog joins me, but when my attention averts from petting to watching the lesson, he effortlessly departs by leaping out the viewing window.

My high-school French is rather dusty, too, but I have come to learn for the day, optimistic that dressage is a universal language. Catherine’s first student appears to be new. She begins by asking her student to lower the horse’s neck and ask for flexion to the inside at the poll. She is not satisfied, so she asks the student to dismount so that they can work with the horse from the ground. She passes the outside rein over the horse’s withers. Catherine stands by the horse’s shoulder, holding the reins as if riding. She asks the horse to soften his jaw and flex to the inside so that his nose is in front of his inside shoulder. She then steps into the horse’s space, asking him to go forward while yielding his shoulders and hindquarters in an expanding volte so that he becomes soft in his body and in his mind. She does this in both directions. When the student gets back on, Catherine asks her to go immediately into canter, keeping him round and pushing forward through his body as they move down the long sides of the arena.

After the lesson, Catherine encourages me to go out to the outdoor arena where Michel’s first lesson of the day is under way. The master himself is sitting in a gazebo behind A, holding court over a lovely dressage arena framed in elegant shrubbery. Beyond the arena, horses are grazing in pastures thick with grass.

I falter, think carpe diem, and take a seat next to Michel. He is elegantly dressed, spry and crackling with an energy that makes my skin tingle. He hovers at the edge of his seat and hardly seems able to contain his excitement about the horses. He only speaks French, but to my great pleasure, I find myself able to understand him quite well.

His next lesson is with Catherine. She appears riding a smallish plain bay mare. Michel explains to me that the mare is a Holsteiner who came to them with some issues. As Catherine starts the mare in a stretching trot, I can’t help feeling disappointed that the little mare is rather ordinary. Catherine stops to explain to me that they ride the mare two days per week in a snaffle and two days per week in the double bridle. Today is a double-bridle day.

Catherine warms the mare up with canter–trot transitions. After this phase, they take a short free walk break and then the work begins in earnest.

They played with the mare using all of the exercises from the Grand Prix, including the immobile halts. Catherine also rode many transitions between the collected and extended gaits. This work transformed the little mare before my eyes into an expressive, riveting international-caliber-looking dressage horse.

Catherine rode with soft, flexible elbows at her sides. She kept her hands low and quiet, just in front of the saddle. She had the deep, elastic following seat that dressage riders exalt. She rode with long spurs, but her legs hung quietly at the horse’s sides. She occasionally carried a whip, which made her mare very hot, so she picked it up only sparingly, mostly leaving it leaning against a letter.

Often, tiny tweaks were all that Michel needed to give to help Catherine, such as “more angle” or “more energy.” Sometimes the feedback was blunt: “bien,” good, or “mauvais,” bad. Catherine incorporated lots of transitions within the gaits and Michel chided her to make her transitions even more marked. The passion they shared for their work sometimes collided with a spark, but the mutual respect for each other and their horses always prevailed.

At the end, Catherine and the mare marched right up to the edge of our booth and the mare peeked in, her eyes bright and ears pricked. She seemed quite pleased with herself and eager to get her sugar from Michel.

another great training session with Michel. (Courtesy, Catherine Henriquet)

Next Catherine rode an 18-hand, huge-moving but rather lumbering Hanoverian gelding. He was impressive-looking, but I did not think he looked handy enough to do much more than First Level work. They addressed his slow-leggedness with lots of transitions. Catherine also rode him quite fearlessly in giant canter extensions. It was clear she had high expectations of him and expected him to give his best effort. They asked him lots of questions in the form of dressage exercises and the demands of this work improved his agility tremendously. About halfway through, I was impressed to notice that he had become quite active with the hind legs in his canter, enough so that they were able to school canter pirouettes. They were then able to finish his session with piaffe steps and flying changes of lead at every third stride.

Upon returning from a light hack, a working student rode into the arena with the last horse. I guessed him to be a schoolmaster because he was muscled like a horse who had done a fair amount of bracing in his lifetime. They introduced him as a 12-year-old son of Ferro. Michel proudly explained to me that the horse was another of their retraining projects. In just four months, he had so improved with their system that the chef d’équipe of the French team had remarked on his potential to become a team horse.

The working student continued his warm-up in the arena while Michel dictated the exercises. They did deep leg yields, making turns up the centerline sometimes bent to the inside and sometimes counter bent. They also performed shoulder-in and counter shoulder-in down the long sides.

When Catherine returned to take over the ride, they removed the snaffle and put on a double. They worked the gelding through similar patterns as with the mare, incorporating all the dressage movements up to Grand Prix. The piaffe was the weak point for the horse, which Michel corrected simply by reminding Catherine to push his hindquarters slightly out. Throughout the work, the horse developed more and more self-carriage until he, too, became brilliant.

Catherine and Michel’s system was straightforward. The classic movements of dressage, when properly ridden, were used as a tool to improve a horse’s way of going. Throughness was addressed during the work and not as a prerequisite to doing the exercises. The exercises were varied and seldom was any movement practiced more than a few times in each direction. Impulsion was refreshed with mediums and extensions. Collection was emphasized with trot-to-halt transitions in both shoulder-in and haunches-in. Throughout all the work, the dressage movements, particularly the shoulder- in, were used as a means to improve each horse’s suppleness, power and lightness.

The work was fair, but always with a high standard as the goal. Catherine rode with clear expectations and the horses were treated with the utmost confidence that they could rise to the challenge. Each horse blossomed during his work, finishing with increased presence and exiting the arena with a loose swinging walk.

Michel wanted his riders to always keep the hands low and relaxed. “Descendez vos mains” (lower the hands), he often reminded them. The inside hand particularly was to stay quiet, asking only for flexion. The reins were kept fairly short while the neck was kept long by asking the horse to stretch over the arch of his neck. The outside aids guided the horse in conjunction with the rider’s seat. If a horse fell apart or tried to blast onto his forehand, he was halted (and in one instance with the 18-hand horse, backed up), thus reminding the horse that it is his job to hold himself together. The horses learned to find their own balance with longer necks that were not closed at the throatlatch. The lightness came not from the rider letting the reins out, but from the horse gathering himself to do the dressage exercises. There was no ongoing pressure with the reins, the horses were never pushed against the bit and none of the riders leaned against the reins.

Michel turned to me at one moment that morning and exclaimed, “our number-one priority here is légèreté!” Together, Michel and Catherine demonstrated that légèreté (lightness) comes from the horse finding his own balance, agility and joy through the work of dressage.

A Lesson with Catherine Henriquet

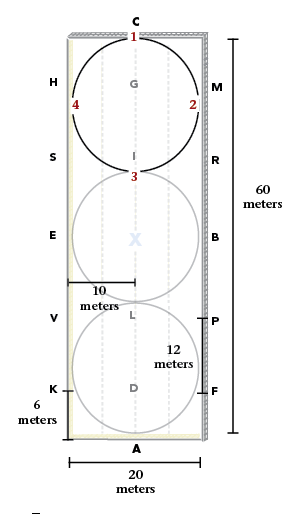

A working student brought out a pretty, gray 8-year-old Lusitano/Trakehner-cross gelding for my lesson with Catherine. He was outfitted in an old Wintec Isabel saddle and a snaffle with no flash. We began with an active free walk and then progressed to a rising trot, with the neck low and stretching. We turned down the centerline and made steep leg yields toward R and S in the 40-meter long arena. The canter work was introduced early.

Catherine guided me through the following exercises:

• 20-meter circle, shoulder-in, haunches-in

• Shoulder-in, halt in position, continue in shoulder-in

• Haunches-in, halt in position, continue in haunches-in

• Medium canter to refresh

• Canter plié (leg yield)

• Canter half-pass

• Counter canter, keeping energy

• Flying change on diagonal

• Lots of changes within the gaits from extended to collected

• 10-meter volte, keeping inside flexion, using the whip on the outside shoulder if needed, thinking canter pirouette and sitting back.

The 45-minute lesson was broken up with four active walk breaks. During the breaks, Catherine counseled me. She noticed that I go from rising trot to sitting trot when I ask my horse to collect. I should stay consistent, sitting or rising through tempo changes. I must turn my shoulders more to turn the horse and to create the correct angle in the lateral work. Also, I must keep my position no matter what! Especially when the horse loses it, I must not allow my seat to be changed to accommodate the horse. The rider should sit well and expect the horse to adapt to her. I tried to picture Catherine, as her beautiful classic position never wavered when she rode.

She urged me not to confuse slowing down with collection. My half halts needed to be quicker; one mustn’t hang on the reins to collect. Finally, she reminded me to keep my aids distinct, saying, “Remember, hands without legs, legs without hands.” With that iconic advice, my Henriquet experience was complete.

Special thanks to Amelia Irion for her help with translation and to Catherine Henriquet for her permission to tell this story. For more information, visit henriquet.fr.

Louisa Zai Ravaris has been horse crazy since age 5, when she left home for a summer of horse camp. This lifelong passion has led her on many marvelous learning adventures. At home at Helicon Farm in Fort Worth, Texas, she has trained her homebred horses from first haltering up to Prix St. Georges. She trains, teaches and writes for other equestrians who share her ideals of harmony and friendship with horses. Dressage at Devon is her mecca, where she has scribed, ridden in exhibitions, competed in young horse classes and dreams of riding Grand Prix someday. She is currently excited about her new partner, the KWPN Figlio dei Fiore, and riding with coach Pati Pierucci.