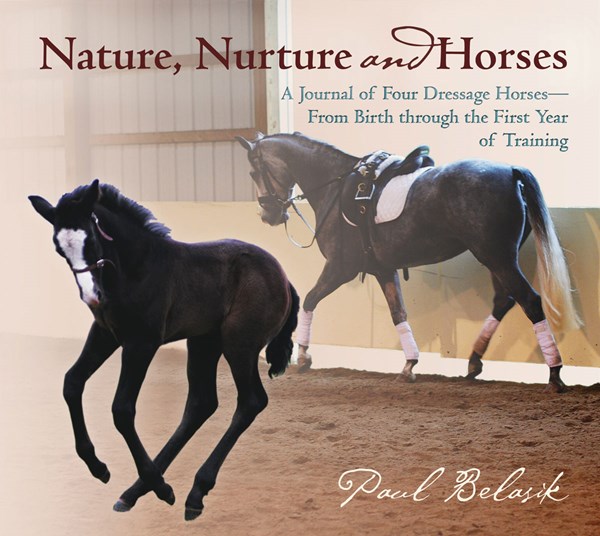

Nature, Nurture and Horses: A Journal of Four Dressage Horses from Birth through the First Year of Training

By Paul Belasik

143 pages, Published by Trafalgar Square Books and available at HorseBooksEtc. com or by calling (800) 952-5813.

You have to hand it to a veteran author like Paul Belasik, who keeps coming up with books about horses with remarkably fresh angles. In this one, he frames his 40-year-old practice of starting young horses with the centuries- old classical method he learned from Europeans. An enjoyable and entertaining writer, he has an ample intellectual view of the world that layers his work, plus an unabashed love of the natural world, combined with a scientific rigor regarding the role of equine biomechanics. It is rare stuff, indeed.

Belasik’s book is about four horses born in the spring and summer of 2007, siblings by the same sire, but out of different mothers, with obvious and distinct personalities, that were to be started under saddle. These include Kara, the firstborn, black with a great white blaze, mother unnamed; Corsana, out of a Thoroughbred mare; Escarpa, the only colt, out of the Hanoverian Denali; and Elsa, out of the Andalusian mare Delirio. They will respond to training in their own way, from fearless and trusting to shy, or with their own opinions about the process.

For me, the very heart of the book is the information about the horse’s neck and what to do about it. “We need to first shape the neck of these young horses to eliminate their tendency to use it for balance or fall forward onto it as we ask the horses to go forward,” he says. “They need to learn to balance with their bodies and their hind legs. Beginning with the neck is part of a logical and progressive system assuring that one day you don’t begin to ask for a shape or movement for which the horse has had no preparation. The beauty of starting horses with this goal in mind is that you can teach the correct form to a body that is malleable and not yet set in its ‘bad balance’ ways. The horse learns how to hold his body and move correctly before he is mounted.”

About the longer neck, he writes that it “takes careful shaping, adjusting the side reins frequently and encouraging the neck to extend in the proper uphill arc in the sense of a long and patient bonsai training. When you begin to plan a strategy for shaping the horse’s neck, the horse’s physical conformation can never be separated from his psychological conformation. A horse can have the perfect neck shape, yet is such a resistant personality you may never get it as correct as it should be. I feel it is easier to overcome physical traits in conformation than it is to overcome psychological faults. Disposition must always come first in selecting a young horse,” Belasik writes.

There is so much more in the book— everything from weaning to first bath, use of the cavesson, first rides, what happens during first canters and so on—but I am running out of space. Still, I feel the sculpting of the young horse’s neck is the essential lesson to be learned here, and I hope I am able to entice readers to study this book, whether they have a young horse or old, as it is very likely to influence their thinking toward Belasik’s methodology.

As he writes, “For 40 years, the classical system has proven to me that it is the best way to prepare sound horses for riding careers, rehabilitate unsound ones and keep working horses healthy so that they enjoy a long, active life.” This test of time is an irrefutable one.

The only reservation I have about this book is that, in his introduction, Belasik says that neither he nor his assistant and manager, Andrea Vela, wear helmets while working with young horses. He says that in all his many years of starting young horses, he has never had a horse even slightly injured and no rider has taken a single fall. He adds, “safe riding is a consequence of good judgment” and that “wearing a helmet or inflatable vest by a reckless and ambitious rider or trainer is not going to save them from accidents.” He leaves it to the serious adult to make his or her own decisions about risk-taking, and so I must be content with that, as the richness of the content of this book is way too valuable to bypass.