A correctly executed lateral movement is very effective for retraining a poorly ridden horse and generally doesn’t require a great expenditure of energy, especially at the walk. There is more to say, however, to appropriately value the importance of this exercise and the importance of the rider holding her hand higher.

As an Amazon Associate, Dressage Today may earn an affiliate commission when you buy through links on our site. Products links are selected by Dressage Today editors.

A few years ago, I became more conscious of the importance of calmly executed walk work through my experiences at the farm of Anja Beran in southern Germany. Iberian horses were regularly worked laterally at the walk. This is of great importance when developing suppleness, especially in a horse in retraining. A variety of walking exercises, from simply stepping over on up to the lateral exercises, is of inestimable value for the retraining of poorly ridden horses.

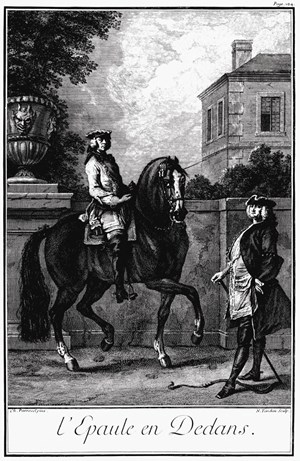

François Robichon de la Guérinière advises about the shoulder-in: “I regard this exercise as the beginning and end of all training. It builds the horse throughout his body. It is true that every ruined horse becomes just as supple as previously when one works a few days in shoulder-in.”

Although his time frame is certainly very optimistic, de la Guérinière recognized the extraordinary rebalancing and loosening effect of lateral work on the back. In addition, there is a significant direct and indirect effect on the poll. Mouth activity begins, which contributes to suppleness of the poll.

More than 200 years later, Waldemar Seunig wrote about chewing: “A simple and unfailing method, when done right, of enlivening an apparently dead mouth and encouraging a resistant neck to stretch to the bit is the turn on the forehand while moving. The hindquarters are pushed around the forehand, which makes a small circle. In contrast to a turn on the forehand on the spot where the inside front leg creeps back or stays planted, the whole horse goes in regular steps in this loosening exercise, without being allowed to stop or lean. At any time, he is able to change from steps moving around two concentric circles to straight ahead.”

Seunig doesn’t describe the biomechanical effect of this movement on the back of the horse. However, he certainly knows the effect. He talks about getting horses with resistant necks to stretch to the bit and chew. A horse with a blocked back tends to move backward when asked to turn on the forehand. Executing the turn while moving diminishes this tendency and significantly increases the benefit. Moreover, crossing of the front legs significantly loosens the shoulder region.

Restoring Basic Balance

Practically speaking, there are many obvious benefits to asking for a turn on the forehand. The horse begins to chew, which in turn leads to poll suppleness and rounding or at least some improvement. It has been my experience that about 90 percent of horses have a tight back. Stepping over relaxes the back through the upper muscle chain, especially the lumbar portion of the long back muscles, and leads to the back lifting into the desired position. The rider suddenly feels movement in the previously “dead” back.

In adult horses, a very effective stretch of the neck is almost always achieved through stepping over—this stretch lifts the back behind the withers and improves the balance. “Swinging,” as described by B.H. von Holleuffer, requires lifting and balancing of the back; if successful, then rhythm, suppleness and contact all improve, as does impulsion at the trot. A decisive step in the direction of basic balance is achieved.

Stepping-over exercises also lead to the horse tuning in to the leg of the rider, and with steadily improved sensitivity. Tuning the horse to the subtlest leg aids is an important and critical goal—then the horse responds to the “breath of the trouser leg.” After a few days of practical application, most horses move sideways when asked by a rider’s supple seat; the lower leg plays only a very light monitoring role. In this way, the rider learns to apply the lightest aids and the horse learns to react to the lightest aids. A reflexive contraction of the external oblique abdominal muscle follows, which leads to a willing and quiet lateral stepping over or stepping under of the hind leg. Horse and rider both profit tremendously from this fine-tuning—each communicating with and understanding the other.

Sit Supplely and Aid Sensitively

Practically speaking, there are a few key prerequisites for success. The seat of the rider must be supple. Any initial resistance of the horse should be addressed with skillful and sensitive use of the whip aid and not with spurs. From the beginning, you must avoid sitting on the horse with squeezing legs. If the rider clamps the adductor muscles of the thigh, that tension is transmitted immediately to the body of the horse, and the horse clamps, too. If the rider sits with a tight back on her horse, exactly the same thing occurs in the horse: The horse then feels “heavy.”

The positive benefits mentioned above can be achieved only when the rider sits supplely and aids with feeling. Sometimes with horses that have been poorly ridden that is not easy; nevertheless it is essential. Successful retraining of a horse with these exercises requires calmness, mental relaxation, physical suppleness in the rider and slow movements. The tighter and stiffer the back, poll and haunches, the more important it is to do this exercise slowly. You may understand this from your own body with a muscle cramp—you can loosen it only through very slow movement. Mobility and promptness require supple muscles. Moving sideways quickly is not effective with a tense horse and can even be disadvantageous as the horse learns to run away from the rider’s seat aids.

Correct Use of the Reins

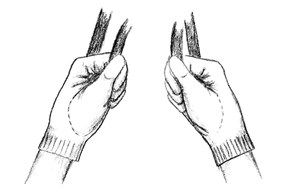

Seunig describes the practical execution of stepping over and the special use of the inside hand: “The process is as follows: The horse in a snaffle bridle stands straight with no lateral bend. The horse is pushed by the right lower leg to the left in calm, regular steps. The rider’s left leg guards against hurrying and drives quickly forward when the horse’s forehand wants to stop. The right hand lifts with arm outstretched from the shoulder joint, toward the ears, without any pressure, while staying in light contact with the corner of the horse’s lips. The right rein is vertical. The left hand maintains its normal position, the ring and little fingers open softly and vibrate.

“The stimulus acting on the right side of the mouth is released as soon as the swallowing movement of the tongue leads to chewing. At the same time, the right hand is lowered back in place. The left leg that has up until now acted as a barrier to prevent the horse from speeding sideways, now wraps against the body of the horse with the same pressure as the right driving leg so that the horse now leaves the volte and moves straight forward. The rider gives the reins forward and praises the horse.”

Seunig describes both the benefit of stepping over and the importance of the raised hand. He clearly says not to pull, rather only to feel the corner of the horse’s mouth. There is a key point of learning here regarding the correct position of a rider’s hand: “The hands are vertical with the thumbs on top, about four fingers apart from one another and enclosing the horse’s neck with the reins. They are held at a height that allows the lower arms and reins to form a straight line.”

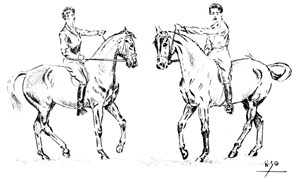

This rein usage defines an ideal situation: a hand position that controls a balanced and “through” horse. While this ideal picture of a balanced horse is what many riders dream of, reality may look a little different—the majority of horses demonstrate problems with balance to varying degrees. As a result, there are almost always issues with bit contact. An overwhelming number of riders fight with horses going against the rein, behind the bit or hanging on the reins. When the hand is held dogmatically in place, many riders start pulling with a deeply held hand. Very often we see riders at all levels and in all disciplines tending to pull the inside rein hand backward toward the thigh.

Every backward pull on the rein by the rider calls forth a counteracting pull by the horse against the rider’s hand pressure. An attempt to mechanically force a head/neck position always leads to defensive tension in the horse. Every living creature reacts in this way. It is the kernel and essence of classical riding theory to achieve a beautiful external frame that reflects balance and harmony as the result of correct training. However, when this desirable frame becomes a prerequisite, rather than encouraging this desirable frame through correct riding and exercises, a rider may be compelled to mechanically force the position. A deep and/or backward-pulling hand leads to a tense poll, which leads to a tense back and then to stiff haunches. The horse is strengthened in his natural crookedness, and damage occurs to his natural gaits. In an extreme case, motion is disturbed and the horse develops rein lameness. Structural injuries and lameness issues are other consequences that may develop.

A dogmatically placed, immobile hand causes this vicious cycle. Every trainer wants a sensitive hand placed exactly between the supple horse’s mouth and the elbow of the rider. Because large numbers of horses are in need of retraining, the rider must be advised on a reasonable procedure that enables horse and rider to find suppleness and harmony.

Experienced trainers know that every pull on the horse’s mouth results in not only increased tension in the horse, but it also frequently has a bad effect on the rider. Many riders sit with their whole body cramped as a result of persistent struggles with the horse’s mouth. The rider’s back tightens to resist being pulled forward by the horse’s head. And to avoid tipping forward in the saddle, the rider ends up clamping her thighs together as an anchor.

Clamping the thighs pulls the rider’s legs up. As the rider clenches with the full of her legs, tension increases through the horse’s whole body. Holding tight with the hands causes the rider’s shoulders to tense. From that position, the elbows, wrists and hands cramp, lose feeling, become rigid and tend to orient backward in a non-ending cycle of tension. Scarcely anyone succeeds in breaking out of it without help. The objective is to reorient the rider’s entire riding focus on suppleness and sensitivity and to drive with an active seat in order to achieve harmony.

Chewing reflex from lifting of the rider’s hand—In retraining a horse, the struggle is to avoid fighting against massive stiffness in the horse’s body. Loosening this tension requires an absolutely supple rider. With few exceptions, when retraining, the hand should never go below an imaginary line drawn from the rider’s elbow to the horse’s mouth. A hand sinking below this line pulls on the horse’s mouth. Since most horses react to every backward pull with defensive tension, a deep hand position is to be avoided. To counteract this tendency, it is very effective to lift the hands (without pulling), especially on the inside rein. Seunig describes that through an interplay of the aids, using the reins in this way releases a chewing reflex, encourages poll suppleness and as a result, poll rounding. That is the first prerequisite for good stretching. A common saying advises: “A high hand rounds the neck; a low hand lengthens it.”

If the hands are deep, they should give. The exception is a horse that has his neck so extremely curled that he won’t accept the bit with the methods described above. In such a case, it can be useful to lower the hands and passively wait for his counter-pull. When the counter-pull comes, allow it and follow it as the horse moves his head forward. Such measures are best executed by experienced and confident trainers.

Independent seat and subtle hand influence—It is especially important to sit independently: Only when hands are independent of the body can the rider react appropriately to every situation with her reins without causing tension in the horse’s poll and neck. Within the framework of gymnasticizing the horse, there is one reaction that must be avoided, namely pulling backward on the reins so that the angle of the lower jaw becomes smaller; that is, mechanically forced longitudinal flexion. Such a use of the hand is only to be tolerated for a short time and only as a necessary educational method for a horse that is deadened to the feel of the rider’s aids. A horse that leans on the bit and no longer reacts to several pulls on the reins must eventually be stopped sharply and mechanically. The goal of such a measure must always be to resensitize the horse’s mouth. Such a correction is considered successful when the horse begins to respond to softer rein aids.

With the young horse, you should strive to develop balance systematically. Correct contact with an active mouth begins when the horse starts to find his rhythm and swing his back. If the rider carefully begins using her seat at this point, the horse will begin to chew. It doesn’t make sense to get the horse to chew artificially through reflex. Seunig writes: “Experience shows that every attempt to create an active mouth is bad if it is before the horse is ready for it. The horse is prepared through months of gymnastic work that consists primarily of forward riding on straight lines with careful changes of tempo. Then progress can be realized by making the mouth more active through discreet influences of the hand. The course of dressage training accelerates. According to the principle of reciprocal influence of all the muscle groups in the moving horse, progress in training the mouth to soften improves suppleness of the body. We aren’t talking about riding the head of the horse or about the primary importance of the hand. On the contrary, the back and the leg are of primary importance. It is only being suggested that in the concert of aids there is a role to be played by a sensitive hand that ‘shows the way.’”

Seunig makes it clear that the seat of the rider is the foundation. A sensitive hand used with skill can have an important and positive effect. The classical way of training is clearly defined and irrefutable as a positive influence. Nevertheless, I believe that an experienced and sensitive horseman can match her aids to circumstances as necessary. Why not softly stop an unbalanced and tense horse through light lifting of the outside rein when the “classical” half halt would only cause stiffness and resistance in such a horse?

Balance Disruptions Caused by Training Errors

Many competition, riding and pleasure horses have not been correctly trained. Small disruptions of balance that don’t create significant tension in the horse’s body are not necessarily damaging and subsequently pose little problem for the horse. Pronounced disturbances will almost always lead to health problems.

As a veterinarian interested in orthopedics and a pferdewirt with a major in riding, I am regularly confronted in lameness exams with statements like:

“My horse doesn’t go on the bit.”

“My horse runs away with me.”

“My horse is so crooked.”

“My horse is not controllable.”

“My horse has become so stiff it isn’t any fun to ride him any more.”

A large number of riders are struggling with problems like these. They are often on their own without professional help. The principles of classical riding theory provide the answers; but they must be appropriately applied.

When you have significant difficulties in training, the condition or sensitivity of the horse’s back is usually the main problem. Horses can be categorized in three different ways that explain just about all of the listed training and riding issues: leg movers, hyperflexed back movers and the horse that has fallen apart.

The balanced back has positive tension, is actively carried by the musculature and is relatively relaxed in every situation. Deviating from this state, there are back positions that make it impossible for the horse to move freely from negative tension.

The back mover is a balanced horse in the sense of classical riding theory. Only one position of the vertebral column of the horse’s trunk allows all the back muscles to work with dynamic suppleness to characterize the back mover. There is a distinct relationship between the position of the back, the position of the neck and later the position of the pelvis (croup), which the rider influences with her aids, such as the hands, the seat (quality, weight) and the leg. The quality of the seat has an enormous and direct influence on the suppleness of the horse’s back.

The most frequent balance disruptions are characterized by:

1. The correctly positioned, but tense, stiff back.

2. The back that is lost downward (hollow back, leg mover).

3. The back that is lost upward (hyperflexed back mover).

4. The collapsed, hollow back (the horse has fallen apart).

In all these disturbances of balance, the back musculature no longer can fulfill its natural job as the center of movement. A citation from Udo Bürger’s book, The Way to Perfect Horsemanship, remarks on this subject: “In summary, the long back muscle is a true muscle of movement. It is active in forward movement and in establishing a secure carriage in movement, but was not meant to carry the rider‘s weight. The back is connected with the forehand through the broad back muscles and with the hindquarters through the large croup muscles. In this way, it is plugged into the rhythm of the movement and cannot be isolated.”

With all horses in retraining, it is more or less a job of getting the back into position and working again. The long back muscles of movement must become supple, powerful and elastic again.

Dr. Gerd Heuschmann, a Bereiter, equine veterinarian and author, explores what it means to be a responsible rider in his latest book, Balancing Act: The Horse in Sport—An Irreconcilable Conflict? Known for his strong opinions against hyperflexion (rollkur), Heuschmann addresses whether it is indeed possible for riders in equestrian sport to put the good of the horse first and foremost—most pointedly above ambition and fame. With illustrations of the horse’s anatomy and how it is impacted by various riding techniques, the book presents further proof that, although some steps have been taken to prevent the use of forceful techniques in the training of top horses, many sport horses still perform in discomfort. In the following excerpt, adapted from his book, Heuschmann discusses retraining poorly ridden horses, and provides several examples of poor riding in an effort to prevent similar pitfalls. Used with permission from Trafalgar Square Books.