With the young or novice horse, our main preoccupation has been to allow him to go forward within the gentle framework of our hands and legs. Transitions require the interaction of the whole body, the legs playing a bigger part than the hands. The take and give of the fingers for an upward or downward transition is generally accompanied by the take and give of the rider’s legs, seat and upper body, which influence the whole—although not necessarily in the same moment.

As the horse matures, we should become more aware of the effects of our upper body and how it affects the seat. As with the aids of hand and leg, the seat can either take or give. The “take,” of course, refers to collection. If more lessons for the higher-level student were devoted to the seat aids, we might see much kinder hands and there would be less inclination to shorten horses through the neck in order to remain in control.

So what exactly do we mean by the take and give of the rider’s seat? First, let us clarify that this has absolutely nothing to do with pushing, which may well hollow the horse’s spine. On the contrary, the seat aids should be subtle and almost invisible since they rely on the tone and elasticity of the rider’s abdominal, back and adductor muscles, which are not so easily observed.

Second, no seat aid can be given with real precision unless the rider sits still! This may sound like a contradiction but, as with the hands and legs, unless we are quiet to start with, the horse will not notice when an aid is given. It is also vital that we sit as close as possible over the horse’s center of gravity, i.e., up to the pommel (waist to hands) with the seat bones resting in the center of the saddle.

Up the Body

The rider’s body acts on that of a horse rather like a bridge. The bridge must, of course, allow energy to pass through and under. For this reason it requires a supportive structure and firm foundations. When it is vertical and well-rooted, gravity keeps it in place but, in relation to the horse, this can only work when the rider sits up with supple loins and learns to let go with the legs.

From open hip joints and relaxed legs, you are more able to stimulate the horse sufficiently to produce and gather the energy required in collection. Ask at the girth with light, swift touches of the lower leg to bring the horse’s back up and think of sitting up and remaining above it all. Never ever push down; instead allow gravity to keep you in place.

From now on, everything we do with the upper body and legs will change the feel and the pressures of our seat on the horse’s back. The bridge will collapse if the abdominal muscles are slack; by firming up with the shoulders, back and sternum and with the navel to the fore, you can control this stored energy at will. “Up the body, down the weight!” is the maxim at Vienna at the Spanish Riding School.

Down the Weight

To stay in balance, the entire underside of the pelvis from front to back must contact the saddle. A good saddle, rising at the twist to support the crotch, will direct the rider’s weight to its lowest point through the seat bones (i.e., a good hand’s breadth from the cantle) and as close as possible to the horse’s center of balance. This all-embracing contact of the rider’s seat promotes a quiet, elegant and upright position which allows for subtle changes. It has come to be known as the three-point seat, with numerous references in both ancient and modern classical books, and it is practiced at the great riding academies of the world.

The taller we sit, the greater the downward pull of the legs. The stretch should be through the front of our thighs, into our knees and thence to the ground. This keeps our seat central, making it easy to “let go” with our legs—so important for the gathering or collection of the horse as we advance his education. The feeling is not unlike that of riding without stirrups. Once we tune in to gravity, the sheer weight of the leg falling away keeps us rooted. We should never worry about losing our stirrups again.

Opening and Closing

Whilst the seat should remain more or less neutral for riding the young horse forward or for hacking, dressage proper requires greater awareness. How we use our seat should never be forced or contrived, but every change of balance and gait will rely on subtle changes within ourselves. With practice, these fine aids should develop naturally, since every movement we make on the ground is based on similar principles.

In simple terms, the pelvis acts rather like a gearbox. In riding, its position—our seat—can regulate just how much energy we retain or let through. For example, in bringing our shoulders fractionally behind the vertical, the pelvis “opens,” allowing more energy to be released from the hindquarters to the forehand. When correctly done and assisted with appropriate leg aids, we now have an effective driving aid. This is, of course, the opposite of how we use the seat for collection.

By contrast, when we sit in the vertical, knees down, legs back a little, the pelvis is more closed in front. This complements the bringing together of the horse’s energy—the word “collection” being very appropriate. Tilting the balance to the front of the saddle allows the horse to flex his back, step deep underneath and produce shorter, more elevated steps. The more we draw up, the more we take his energy up with us. This, in turn, brings control, cadence and balance to the gaits.

As already discussed, moving the legs too much behind the vertical may put on the handbrake. This works very nicely for rein-back as we relieve pressure from the back of the saddle, but we must always release, sit up and return to neutral the moment we want to go forward again. All these nuances work together to produce a fine balancing act, but take care never to overdo things. The seat aids should be virtually invisible to anyone watching.

Higher and Higher

Later in the horse’s training (and always subtly counterbalanced by the raising of the rider’s center of gravity), a further redirection of his energy can lead us to the high school airs. Freeing up the horse’s loins facilitates the piaffe and passage—when the impulsion is held in a state of bubbling suspension—and all this will be an evolving process. We must never rush collection. “Contained” energy transforms itself into beautiful movements in its own time and according to the strength and the ability of the horse. Having said that, often the most collected movements are offered quite spontaneously by a fit and generous horse.

Checklist

At this stage of riding, it is important always to have a mental picture of your entire body and how it impacts the horse’s back. Make no mistake, despite the latest numnah [saddle pad], or the stuffing and padding of a beautifully crafted saddle, every move we make is felt.

Disciplining oneself should translate into feeling what the horse is feeling. We have to listen as well as act. Any form of tension or imbalance should be relayed back through the seat of the pants. We learn to make small but meaningful changes of weight, always returning to neutral in between. Personally, I tend to “look down” on myself when I ride. Others prefer a series of checks: Am I sitting square? Am I vertical? Have I kept my navel and sternum forward? Has my inside hip maintained position? Has my outside hip opened sufficiently? Are my knees sufficiently deep? Is my neck at the back of my collar? Are my fingers and ankles relaxed? All these, practiced on a daily basis, are very useful.

Halt

Of course, many riders use the seat aids without ever thinking about it. They may never have had a lesson in their life, but by conditioning themselves and their horse to what works, they develop the feel for opening or closing the door. Good riders will scarcely use the rein for halt since the combined aid of seat, legs and upper body does it much better. Their downward transitions will be smooth and seamless.

Bad riders think impulsion can only be stopped at the horse’s mouth—by which time it has generally gone too far. They have no comprehension of controlling it from the center and have to rely on stronger bits and harsher aids, which invariably hollow the horse. As French riding master Francois Baucher famously wrote: “I like the horse to be behind the hand and in front of the legs, so that the center of gravity is placed between these two aids, as it is only on this condition that the horse is absolutely under the control of the rider.”

Collection First

Clearly, the more we are able to develop the weight aids, the better our riding. For me, collection has to come before extension, since without the gathering of energy there can be no serious releasing or lengthening. It should go without saying that the more we wish to collect the horse, the more we need impulsion.

To start, it may require something of a juggling act to preserve the flow of energy from the hind legs and to collect or keep it at the ready for the next movement, be it sideways, upward, backward or simply more forward. No one can teach you how to do this, but riding a fully trained and collected horse can at least give you the feel, so you can gradually develop it for yourself.

Half Halt

It is not just in riding that we learn to harness energy. Most athletes, and particularly dancers, ice skaters and gymnasts, know when to keep it in reserve—to hold or fix with their bodies—and when and how to allow it out—sometimes in a great surge! And, of course, all this has nothing to do with the hands!

The half halt can be like this. Remember this is not a full transition, but the feeling could be described as preparing for a transition. It should be a momentary instruction—a second’s check or fix—prior to sending forward or rechanneling the impulsion for whatever is required next. Try not to lean back in the half halt. Rather, sit up with shoulders back! A consequence of the half halt will be a reduction in the length of stride, but we are rewarded with higher, lighter steps. In the early days, do not be greedy with these or you will end up with choppy gaits. As with everything in riding, we must work the horse both ways—forward and more together—to develop his strength and understanding. It’s a very gradual process.

How?

Unfortunately, many people think the half halt is only to do with the hands. Many draw the hand back, which only invites resistance. Try instead to think of half-halting through your core as you close the fingers. This will be felt down the length of the rein and if this is not sufficient, then raise the hand gently, but only an inch or so. As you do so, breathe, draw up and hold—through the small of the back. Let the breath out when the horse obeys and your hand will automatically give again.

This feeling is generally transmitted all the way through the seat. A correct half halt allows the horse to draw the hindquarters deeper under the rider’s center of gravity. In so doing, the well-schooled horse will bend his joints to greater effect and learn to “sit.”

As with a ballerina, it is from those moments of “hold” through the rider’s core, back and pelvis that the balance is perfected—for whatever maneuver is requested next. In the shoulder-in, for example, I always think of a moment of fix, to allow the horse time to step under, to flex his joints and to take his weight back. In this movement, and in half pass and canter strike-off, I would half halt with the outside rein alone.

Fix, Take and Give

It was [riding master] Nuno Oliveira who introduced us to this perceptive little saying. Anyone who attended the Annual Conference of the Association of British Riding Schools (ABRS) in 1987 and 1988 will remember this advice being given out to every rider on every horse. If the horse is heavy on the hands and powering on rather too much, say in trot on a straight line, one would probably use both hands. The feeling is subtle. The fingers close very firmly, very quickly.

With some horses, a slight rotation of the wrists might help, and there should be a very slight upward influence to the action, but never at the risk of jerking. With it comes a corresponding “hold” through the wrists, elbows and shoulder joints. The “fix” feeling transfers right down the rider’s back and, if anything, the seat bones should move a little forward.

The moment the horse changes his posture, the hands must give again. Once accepted and understood, half halts will gradually be employed more and more as we progress toward full collection. They eventually become so refined that they comprise a vital part of the collection process.

Weight Back

Strength and suppleness behind come from the judicious and repeated practice of many different maneuvers—start and stop, straight and bend, forward and back, right and left, together and stretched. Now that we understand the main principles of the aiding process, we will be in a much better position to ride the lateral exercises accurately and with a deeper understanding. The shoulder-in is always considered the first of these, since it not only transfers weight to the haunches but, done correctly, will engage the horse’s hip, stifle, hock and fetlock joints. That is the key to lightness and collection.

Everything Is Connected to Everything

To understand the different “feels” required to bring about collection is very personal. We have concentrated on the seat here, but remember—nothing in your body works in isolation. Every single part of you, even the way you carry your head, will have an effect on the feel of the seat in the saddle. Collection comes from knowing how much to regulate the flow from behind, but without energy you have nothing to play with. Bringing the weight back must never restrict the horse; it simply allows us to gather him so that the work can flow with more brilliance the moment we release. In human terms, it’s similar to “setting one back on one’s heels”—a momentary pause before doing something extraordinary.

Things to Guard Against

Remember, too much of any one exercise will tire your horse’s muscles, ligaments and joints. There can be no true collection where tension or discomfort is present. Solution: Introduce variety in everything you do and collection will develop as the horse becomes more elastic and fluid.

Think Positive

Look ahead at all times; if our eyes help us control our bodies on the ground, so they will on horseback. Feel for the balance and make small adjustments only as required. Between each and every request, remember to return to neutral. Remember, less is more!

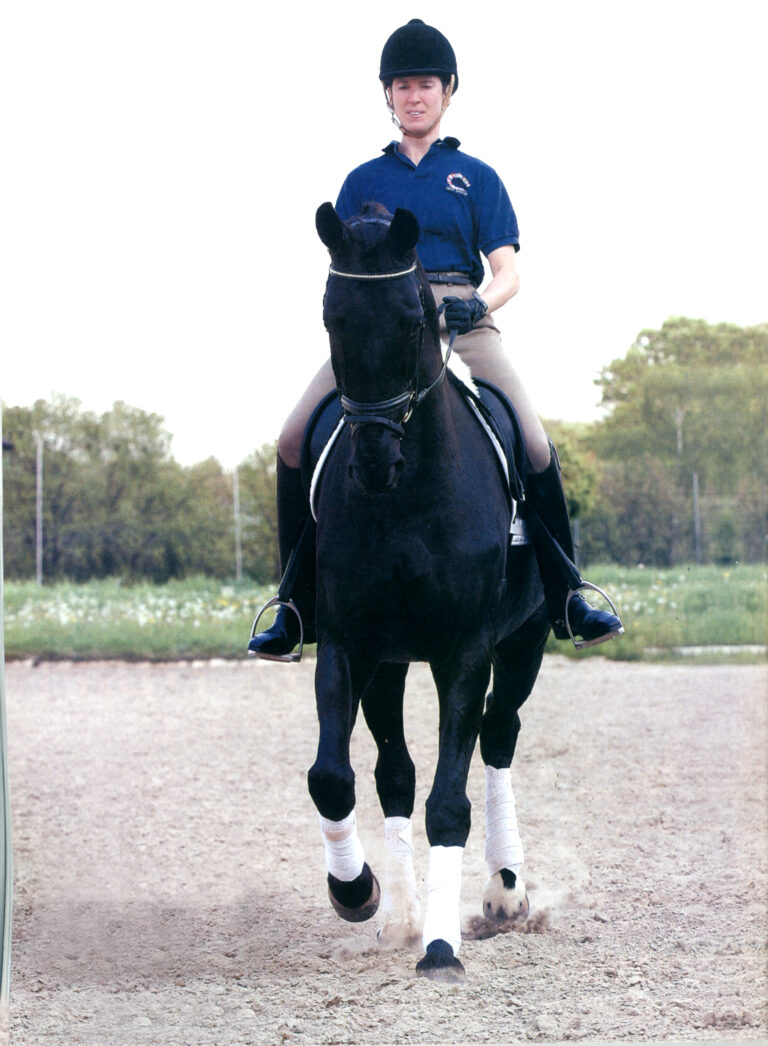

In her new book, The Balanced Horse: The Aids by Feel, Not Force, author Sylvia Loch—an international dressage trainer and co-founder of the Lusitano Breed Society of Great Britain—confirms what equestrians should be doing and what they should avoid when it comes to each and every request they give their horse. Intended for those seeking the elusive art of riding versus competing, this valuable resource will help equestrians develop a better relationship with their horses. In the following excerpt, adapted from her book, Loch discusses the effects of a rider’s upper body and how it affects the seat. Used with permission from Trafalgar Square Books.

Sylvia Loch has written seven books on dressage training. She studied in Portugal and became an accredited instructor by the Portuguese National School of Equestrian Art. Based in Scotland, she teaches and gives clinics worldwide (classicalriding.co.uk).