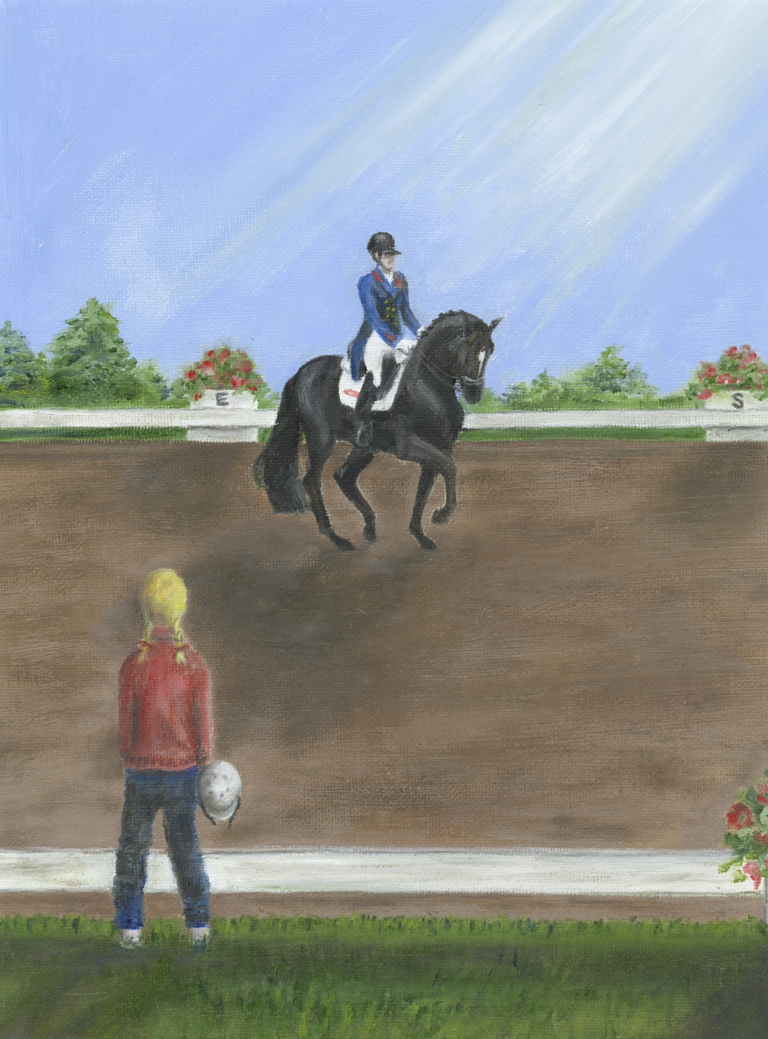

Imagine this: You’ve just completed your first dressage test of the year. You’re riding out of the ring feeling pretty good about your ride even though you know it wasn’t perfect. You see your trainer and ride up to her; your heart is full of satisfaction at your accomplishments. But instead of offering praise for what you did well, your trainer blasts you, criticizing all of your mistakes. Your good mood vanishes, your heart constricts and you wonder why you bother to work so hard.

Now imagine this: You’ve just finished your test, and coming out of the ring filled with excitement, you see your trainer, who points out your good moments, praises your riding and encourages you for the year ahead. Your mind and body flood with joy, and you feel contentment. Thus motivated, you happily commit to making more improvements for the next show.

What’s at the basis of these two contrasting experiences—one of punishment, one of reward? In each case, your brain has interpreted the input and activated a coordinated sequence of neural events that leads to an activation of either a punishment or reward system. This turning off and turning on of different brain circuits produces a corresponding reaction in mind, body and behavior. From a fundamental viewpoint, the horse–rider relationship can be seen as nothing other than sequential brain activity, a process of neurocommunication that determines moods, feelings and behavior. This is true not only for you, but also for your horse.

In the movie “The Matrix,” Morpheus sums up this brain dynamics succinctly: “What is real? If you’re talking about what you can hear, what you can smell, taste and feel, then ‘real’ is simply electrical signals interpreted by your brain.” Knowledge of brain processes in your horse and yourself can help you in your dressage career. Knowing more about how the brain works enables us to forgo those frustrating, depressing experiences and enjoy a more rewarding and joyful life with our mount.

Keep the Prefrontal Cortex Online

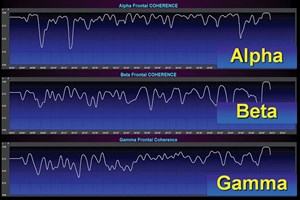

If you were to ask my University of California, Los Angeles-trained neuroscientist husband, Alarik Arenander, PhD, how to go about making better use of your brain and your horse’s brain, he would say, “Keep the prefrontal cortex online and go for dopamine.” He talks like this all the time. Here is what he means: The most fascinating part of the brain is the prefrontal cortex. It is the highest, most powerful controller of all feelings, emotions and behavior. Located right behind your forehead, it is often referred to as the “CEO of the brain,” functioning like the head honcho of your life. It takes in all the information from your senses, motor activity and feelings and orchestrates all your thoughts and actions to achieve your goals. Your horse has a prefrontal cortex, too, and it functions like yours does.

Brain research tells us that any stress-ful or overwhelming experience is known to take the prefrontal cortex offline. “Offline” means that the CEO’s ability to function is greatly reduced and thus, its executive control over brain behavior is greatly minimized. Under stress, the very front lobe of your brain literally shuts down. When this happens, what is experienced is a major disconnect, generally seen as shortsighted, impulsive, fragmented behavior that results in fear, emotional instability and poor learning ability.

A perfect example of this shutting down of the prefrontal cortex came when my husband and I were watching a dressage lesson. The trainer kept telling the rider to make her stretch limo of a horse into a Volkswagen bug. “Rounder, rounder,” the trainer commanded. When the horse started to show signs of stress, Alarik remarked, “Here it comes. The prefrontal is about to disconnect.” Sure enough, the horse soon went into reckless, impulsive and fearful behavior.

We want to try to avoid these kinds of instances and save our horse’s psychology. The prefrontal cortex is your best friend in all cases, and it is extremely helpful to become familiar with how this deep-seated organizer of the brain controls everything important in life. It is essential to keep it online and connected to exert its executive functions for harmony, progress and success in anything you do. “The fundamental rule for any horse–rider–trainer relationship should be to focus on keeping the CEO of everybody’s brain online and happy,” says Alarik. “It is not necessary to get stressed to progress. Productive progress happens by taking small, rewarding steps forward. Sustain that progress and then move on to another goal.”

Make Learning Enjoyable

Dopamine is a small neurotransmitter molecule considered to be the brain’s pleasure and reward chemical. It’s thought of as the Pollyanna of brain chemicals, responsible for the highs and lows of feeling and behavior and in turn, self-confidence and especially motivation. So when you “go for dopa-mine,” it means to “go for reward.”

Considering that we have about 100 billion brain cells, a massive amount of neurotransmitters are constantly being exchanged in the synaptic gap between each brain cell. This activity ultimately determines how we think, feel and act. Again, the same dynamics are also true for the horse, even though he has fewer brain cells than we do. When you experience something as a reward, the dopamine neurotransmitter is released and produces pleasure. We all know from experience that reward shapes positive behavior. It also makes any change, transition or learning experience more enjoyable. When learning is enjoyable, both horse and rider look forward to training with an open mind, and great progress can be achieved.

The dopamine reward system exerts a powerful influence on your relationship with your equine partner. I’ve seen proof of this many times. For example, when I first got my 16.2-hand Dutch Warmblood, PakshiRaj, he came with a long-standing reputation for being naughty. Notorious for breaking loose, he would take the opportunity any chance he could get. No matter how many precautions I’d take, he would still get loose. Needless to say, I became frustrated especially because he was difficult to catch. The more irr-itated I got, the more vicious the cycle became. When I came to Alarik about my predicament, he told me, “Go for dopamine, go for reward.”

I went off to the barn with optimism and a sense of hope. When I first saw Pakshi in his field, I sincerely told him what a good boy he was and tried to make him feel special. Most of the time, he was hard to catch. But this time, to my surprise, as I praised him, he just stood there and let me come right up to him. His response to my praise—my voice, my words and my body language—gave me hope that we were going to be able to create a good working relationship with a mutual respect for each other.

Alarik says to avert danger before it arises. He said that this was a very important principle to keep the whole brain happy. “Begin showing praise and reward before the known bad behavior or habit shows up,” he says. For example, when I bridled Pakshi, he would take advantage of the momentary lapse of restraint by pulling away. To prevent this from happening, just before I unhooked the halter, I would lavish a series of sincere “good boys” on him. To my astonishment, his eyes would show a sign of contentment and he would remain settled and well behaved.

Of course, there have been a few times when he couldn’t resist breaking loose, but when he did, instead of coming at him with my usual agitated communication and body language, I just kept my cool and walked over to him as if it was no big deal. In a relaxed air, I would throw in a few en-couraging words. He sensed my mood and slowly returned to me on his own. The first time he did this, I was astonished; looked up at the heavens and proclaimed, “Hallelujah!”

When Praise is Not Enough

If your horse has some very bad habits, and words of encouragement are not enough to set a platform for a friendly working relationship, then it goes without saying that you have to be firm. You might even have to sharply reprimand your horse to get his attention, stop the behavior and show him who’s in charge.

This brings up an important point regarding the prefrontal cortex and the dopamine reward system: Once you have completed the necessary correction, your horse’s brain is now in a fear-based mode. Although he initially acts more alert and becomes more obedient, this occurs at a cost to his intelligence. With his recent mistake at the center of his attention, he becomes more fearful and concerned about the events that just transpired. At this point, he is not in a position to learn anything. Fear can stop a mistake, but it will not help him learn an alternative form of behavior and, most importantly, develop an intimate, respectful bond with you, the rider.

Here’s the brain science behind the process: After a harsh reprimand, the horse’s prefrontal cortex gets turned off and the amygdala, the fear center, takes over. Since the prefrontal cortex is crucial for developing a sense of self as well as motivation, intelligence, creativity, alertness and learning, having it shut down is problematic. With the prefrontal-cortex function impaired, the amygdala gets activated. This smaller, almond-shaped group of cells is programmed to respond to any unpredictable or dangerous experience by preparing for flight or fight. So, when a horse goes into fear mode and the amygdala is turned on, he becomes temporarily more alert, but less intelligent and less able to learn.

If you want to move past the repri-mand, then you need to settle your horse down and lower the anxiety—that is, reactivate the prefrontal cortex. This is a very important step in your horse’s learning habits and equally important for you, the rider.

One of the best ways to switch off the amygdala and re-engage the prefrontal cortex is to give your horse a moment of praise and then silence. The praise allows your horse to relax. This may take a few moments, considering the various hormones released and the persistent brain patterns. The silence lets him re-connect with his sense of self as well as with you. Just a calm hand on his neck and a soft-spoken “that’s better” will help him settle back into a mental state in which he can learn. These important steps will also help to get your amygdala settled down and your prefrontal cortex back online.

Now, with you and your horse in a calmer, more functional mode, your training will be more purposeful and long lasting. Horses are good learners and wish to please, but they are depen-dent upon you for learning.

Be Consistent

An essential point in this process is consistency. Life and learning are about repetition, practice and consistent behavioral patterns. This applies to your reprimand and firmness as well as your praise and silence. If you are not consistent, then nothing is going to work. So consistency will establish a nonchanging basis to make any change. This nonchanging basis is a mandatory platform for humans to learn as well as for horses. The horse’s brain creates patterns that can become more established and effortless, but consistency is a winner for any form of learning. Be firm, but be kind. Most importantly, be consistent.

Go for Dopamine While Riding

Seeing how well the reward system worked for Pakshi, I started to apply it to my riding. Rather than focus on what he was doing wrong, I focused on what he was doing right. Even if his attempt was only one percent correct, I would focus on that one percent and praise him for it. To my delight, this approach changed our whole working relationship as Pakshi became calmer, more content and willing to learn.

Over time, I noticed that his small percentage of accuracy in completing a request would grow to 25 percent, then 50 percent and eventually close to 100-percent correct. He is now so well-behaved it’s hard for me to remember how naughty and stressed he used to be.

This switch in attitude and behavior has done wonders for my confidence. I am able to relax into my seat more and be calmer and more established in my determination to progress. I feel more in control of myself and my riding. Alarik tells me that as the rider grows in confidence, this reinforces and stregthens the functioning of the prefrontal cortex and dopamine reward system. In this way, learning becomes a win–win for both horse and rider.

As Alarik wisely concludes, “The act of horse riding has to be rewarding. Otherwise, no progress is made, and there’s no reason to be doing it.” You will be amazed at the amount of well-rounded success and achievement you will enjoy by utilizing your new knowledge on brain dynamics of the prefrontal cortex and the dopamine reward system.

Alarik Arenander, PhD, is a UCLA-trained neuroscientist with degrees in molecular biology, developmental biology and neuroscience. His cutting edge brain research has contributed to our understanding of human development and brain potentiality. Since 1999, he has been the director of the Brain Research Institute. Cynthia Arenander (center) is a dressage rider who also makes natural health products at the couple’s Anti-AgingCompany.com. They live in Fairfield, Iowa. Claudia Mueller (left), editor of The Iowa Source, benefits from brain-based dressage with her horse, Vajra. To learn more, visit dressagebrain.com.