Being a good rider mandates accountability. Not only must you control your emotions and physical aids, but you’re also in charge of giving clear messages to your horse. Perhaps most importantly, you define for him your standard of performance, which cannot be high one day and mediocre the next. Your horse must learn to rally and commit his energy to his job, even when he feels lazy. And he must learn to respond to your calming influence when he is excited.

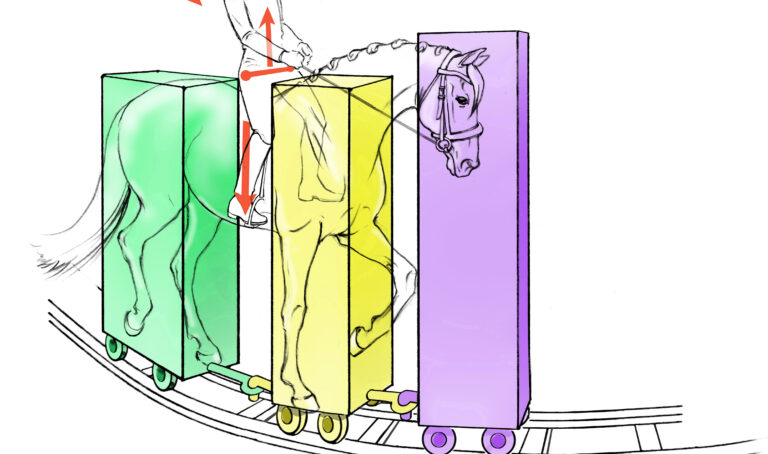

Every aid you give is a chance to control your horse’s level of work. This demands that you feel and respond to every moment. As a responsible rider, it’s your duty to guide your horse to a comfort zone or “predictable place” in both his mind and body. Physically, his body must have the preparation and repetitive feeling of movements within its muscles and joints. Mentally, his mind should immediately access a calm, comfortable state. Then he will be focused on the task at hand, and he will know clearly what is expected from the repetitive practice of motions in his physical body.

Think of this predictable place as though you were a professional athlete so well prepared to compete that when you stepped onto the tennis or basketball court, you could breathe a big sigh of relief and say, “OK, I know what I need to do, and my body is ready to do it perfectly.” There is no anxiety or surprise, no tension or apprehension, just a calm, willing mind in an able body.

Your schooling at home is when you affirm over and over a horse’s predictable place. Basically, you’re taking responsibility 100 percent of the time to make him calm and focused as well as work to his maximum ability. The same goes for Training Level horses as well as for those at Grand Prix.

Develop Feel and Understanding

To understand and find your horse’s predicable place, let’s break the subject down and begin by understanding that, above all, you must develop the ability to feel your horse underneath you. Is he nervous or sluggish? Is he dropping a shoulder or traveling crooked behind? Recall the words of legendary dressage rider Dr. Reiner Klimke: “Feel the moment. Only then can you influence it.”

To feel what’s occurring under you requires a certain degree of understanding your horse’s nature. Begin by knowing what your horse does the other 23 hours a day when he isn’t working. Tune in to your horse’s body language and reactions. As silly as it seems, your riding might improve by doing observation-by just hanging out more with your horse to understand him better. This idea has gained popularity among adherents of “natural horsemanship”-using communication rather than force to work with horses-but it’s applicable to dressage, too, because it makes you more able to give productive signals to your horse. If you know your horse’s reactions to outside influences, you will be prepared to communicate with him. Watch him in the pasture with other horses, and observe his behavior on the cross ties, in new situations and on the trail. Try to get a feeling for how he approaches problem solving. Strive for insight into what motivates his behaviors. Does he enjoy working hard? Is he curious or bold? Learn how he reacts to stress so you can direct his training the best possible way for both his mind and body.

Tuning in to your horse gives focus to your daily training, which will carry over when you go to a competition. If he seems more nervous than usual, you’ll want to use soft, encouraging aids to get his attention. You may want to work on the next level of collection one day, but if you bring your horse out and he’s very uptight and tense, you need to change goals quickly. Your responsibility is to understand why he’s so tense and then to guide him back to a calm mental state. By understanding his psychology, you know how to do this efficiently.

Even though Flim Flam and I have been together at the Grand Prix level for six years, I still might make the decision to stick to basic throughness work and half halts during a work session because some element of the whole picture isn’t good enough that day. If I were to insist on harder exercises, I would only teach him how to perceive these exercises in a compromised way.

My standard to make these decisions is constantly evolving with my skills and knowledge. We, as riders, learn to make better and better decisions with experience, but we must constantly be thinking and evaluating. For some horses, warming up might consist of a lot of walking. For others, it might be a lot of exercises to grab the horse’s attention and build concentration. It’s up to you to listen to your horse and guide him to a reassuring, comfortable mental plane and to create the same quality of work day after day.

For example, at the Olympic Games last summer, Flim Flam almost bucked me off during our warm-up for the team test. That was just a typical reaction for him to what he considered an “electric environment. I had planned on such a reaction in my mental preparation and was, therefore, not surprised, and my concentration was not altered.

Remember that what the horse does is always a reaction to one or many stimuli based on his own perception of the world. We cannot become emotionally involved with these reactions but rather respond to them productively.

Live in Parts of the Test

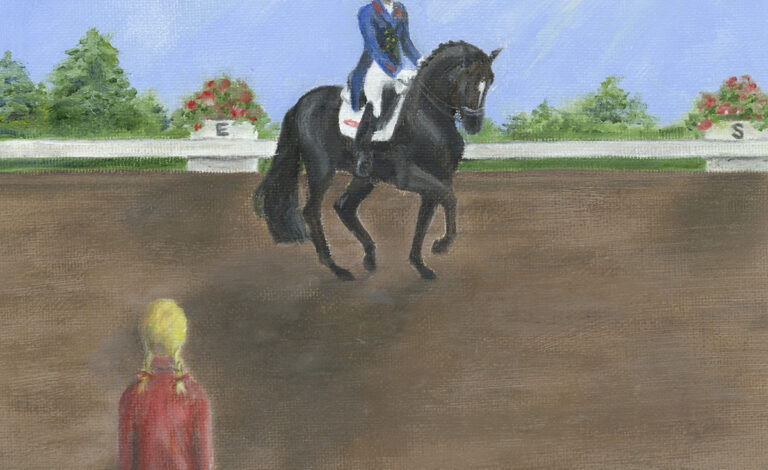

Dressage tests have served for decades as tools to evaluate a horse’s level of training. But it’s time we see them in another light, too: as measures of how focused we are as riders. Since a large measure of rider concentration is imperative when riding a test, regardless of a horse’s level of training, it is a perfect chance to practice developing focus.

Once you develop your sense of feel and understand your horse, you can lead him-and yourself-to a higher level of work by learning to “live in the test” each day. This concept includes putting pressure on yourself to make particular test movements excellent each day. Then the actual competition day will be no different.

Too often in schooling we practice transitions or bending when everything is going well—our horses are soft, round and obedient. But that doesn’t hold us accountable for making these movements their best. We must push our comfort level by adding a little pressure and riding each movement as it’s called for in the test. If a halt is supposed to happen at X, for instance, we must ride it repeatedly at X, demanding the best from our horses. This kind of focused riding keeps our riding standards high day to day. This way, we hold our horses to their jobs.

Structuring a workout to practice movements where they exist in the test involves creativity. The point is not to ride a test from start to finish repeatedly. What’s beneficial is separating out the individual parts of the test and raising the standard each day in your workout. In other words, make a few individual movements your focus that day.

Let’s say you’re going to concentrate on your canter-walk transition at B. You’ll want to do it over and over on the mark, perfecting everything. The aim is to show your horse exactly what movement you’re after and where it needs to happen, exactly on the mark. And then you want to tell him that from now on, the transition needs to happen without losing an ounce of roundness, engagement and straightness.

This concentrated, repetitive practice also gives you a chance to clarify your aids. When you practice something

repeatedly in the same place, your body will get more adept at it. Your aids will be short, quick and articulate, not vague. Since you’ll be certain that the transition is going to happen every time right at B, you won’t be wondering if your horse actually will make the transition. Instead, you can turn your attention to using the correct aids to balance him in the transition and sit up straight. In other words, both you and your horse will have a clear standard and arrive at a predictable place together.

Here’s an example of some practice: riding the canter, transition to walk at B. As you track around the edge of the arena, do a few voltes or other transitions. Canter again and repeat the transition to walk as you come to B. Then do a different set of exercises around the edge, setting yourself up to practice transitioning at B again. Soon the horse knows the movement will happen at B and that he’ll be prepared for his highest performance every time.

Don’t be satisfied with just getting a movement done repeatedly where it belongs. If you think about riding the lines or patterns of the test while making your corrections on top of those lines, your horse’s body will be able to ride voltes and extensions, for example, while you keep adjusting his roundness, engagement, straightness and everything else. This brings his mind to the level of expectation you have for each movement.

Remember your standard cannot vary from day to day. Rather than just practicing a few half passes, for example, make necessary corrections within each half pass to make them as perfect as possible before you end the movement. Don’t accept a compromised standard and go on to other movements. If your horse loses engagement after a few steps of half pass, half halt and add a small circle right there to rebalance and let him know he cannot lower the standard. Then go on to finish the half pass. This is how your horse learns the standard to which you’ll hold him.

Even at Training Level your horse must know that he first trots soft and round up the centerline to a square, quiet halt at X, and then he goes on trotting deep into the corner. His body is confirmed in this high level of expectation, and his mind is quiet because this sequence of movements is a predictable place for him. Finding ways like these to school every movement helps create a memory of correctness in your horse’s muscles for each spot in a test. This is what it means to live in parts of the test.

Mindful Practice Keeps Standards High

At this point, we should recognize the opposing view that too much repetitive practice will ruin a test by causing a horse to anticipate movements and rush through them. This occurs only if your practice isn’t mindful—if you just ride tests start to finish without separating and perfecting each movement. Finding a way to live in parts of the test each day raises the standard and is comforting for horses.

Riding mindfully teaches horses what is expected of them, rather than how to anticipate. Every time you come to your canter zigzag, for instance, your horse brings himself to the level you repeated and practiced. So instead of a boring, anticipated pattern of movements, you’ll turn out a brilliant performance. You will have trained day after day with responsibility. By keeping yourself accountable during schooling, you’ll have advanced yourself and your horse.

Good riding demands a lot of thought and work. Unfortunately, the necessary intense focus can lead to tight riders, who actually have too much on their minds. That’s why it’s important to develop a sufficient level of feel and understanding for your horse. When your horse loses a vital ingredient during his training, such as roundness, impulsion or bend, you are able to rely on your body to sense that and use your mind to bring him back to his predictable place—always channeling focus productively.

Remember that your goal is to make your highest performance standard your comfort zone or predictable place. Part of our evolution as riders is forcing ourselves to be “on the spot” or “in the moment.” Indeed, riding will always mirror life. Your ability to concentrate deeply on tasks in your everyday life, while not getting anxious or uptight, will transfer to the saddle. To improve focus and concentration, some people do nonhorse activities, such as yoga or t’ai chi. Others might enjoy sport psychology training.

Learning the ability to make many adjustments at once while keeping a clear mind may take time and practice, but it will get easier to focus on more than one task at a time. Just keep in mind your standard. Think of your riding as a work in progress—always working to create a higher standard each day.

Sue Blinks rode Fritz Kundrun’s Flim Flam to a team bronze medal at the 2000 Olympic Games. She has been riding the 16.1-hand Hanoverian gelding since he was 3 years old. She also is an American Horse Shows Association ”R” judge.