Rider success is a direct result of certain, very specific, positive qualities. One rider, for example, may have the physical ability and skill set necessary to be an extraordinary classical rider, giving clear, consistent aids in all situations. We might call that being a “skilled dressage rider.” Some riders (not necessarily the skilled dressage rider) have the ability to teach horses to understand what they want. We might call that being “an effective horse trainer,” and that quality can get you pretty far.

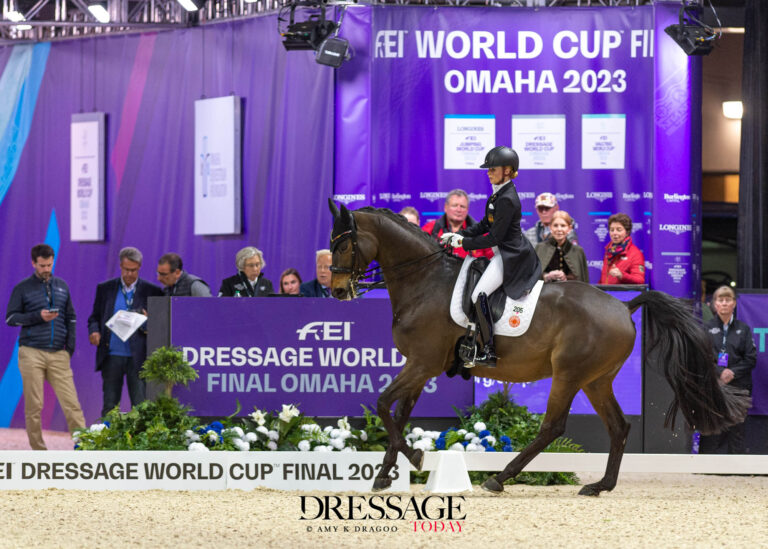

(Arnd Bronkhorst – Arnd.nl)

Some riders have considerable knowledge of dressage theory and others have considerable knowledge of horsemanship and they take exquisite care of their horses. You could be the best rider in the world and not manage your horse’s emotional and physical well-being, thereby preventing the horse from doing his job. People skills are also key. I can think of incredible riders who didn’t have the people skills required. You also need to be able to focus and have a positive, resilient, patient, concentrated personality.

All of these qualities are not necessarily in the same person! But when they are, when one person “has it all,” we’re likely to find her on the podium.

I hope this article helps riders assess themselves, focus on their weak points and work on improving.

1. The Effective Horse Trainer

Many of us can think of trainers who have produced Grand Prix horse after Grand Prix horse—or have great success at the lower levels—but they have no concept of what classical riding is. Even a beginner can be a good horse trainer but not be a good dressage rider if she is able to teach her horse, for example, that she wants a canter depart at F. Regardless of the less-than-ideal riding, the horse has confidence in what his job is and clearly understands what is expected and when. An effective horse trainer can teach the horse through all the levels to understand what she wants.

Horse trainers “speak” horse. They have conversations with their horses through their aids and their responses. The rider communicates, the horse responds and the rider speaks again. It goes on and on. To be a good horse trainer, you need to be able to think like a horse and clearly, consistently convey to him the desired results. You need to be able to administer questions with logically evolving difficulty and simultaneously understand his physical and mental situation. This skill can get you quite far, but you’ll also want to be a skilled classical dressage rider.

2. The Skilled Dressage Rider

To be a classical dressage rider, you need a physical skill set—an independent seat and position, elasticity, the ability to move with the horse’s motion and absorb it without compromising balance, feel and timing. That skill set enables the ability to give precise and consistent aids despite a horse’s resistance, his lack of forward desire or whatever situation might present itself. All riders struggle with the physicality of that.

“Classical” Training.

The word “classical,” for me, means that the horse is ridden without undue stress and in a way that not only does no bodily harm but allows the horse to get stronger and more athletic. The horse moves in such a way that he uses his body naturally and optimally. That means that the rider from an intellectual, emotional, mental and physical standpoint has the ability to figure out how to put the horse in that optimal position.

Horses, on the other hand, are continually trying to process and understand everything you, the rider, do up there—whether you mean to do it or not. They’re playing Pictionary, which is so hard! Riders need to help the horse by being as clear and consistent as possible—black and white. Horses don’t understand rider inconsistencies. For example, if you precisely and correctly ask your horse for a shoulder-in five times and then you lose your focus and let him get away on the sixth and seventh efforts, then you’ve made the request for shoulder-in a multiple-choice question.

When you, the rider, are “consequent” (see sidebar below), your aids are clear and consistent and you teach your horse precisely how to respond to those clear, consistent aids. You give your horse a trail to follow that’s always going in the same direction and is supported by your own body language and your own body parts. Very successful riders are able to think like a horse and are physically able to keep coming up with consistent, clear statements time after time, regardless of the situation. At the same time, the classical rider maintains and develops the quality of the horse and his gaits and her riding is based in classical dressage theory—which brings us to the next quality of exceptional riding.

3. The Theoretical Rider

The successful rider has to have theoretical dressage knowledge. When you understand why you’re doing what you’re doing, your decisions come from a very clear place.

Olympians Christine Traurig, Günter Seidel and Steffen Peters grew up in the European culture of dressage theory, and many others have gone overseas to get the incredible benefit of being immersed in that theory. At this point in history, it’s possible to do that in this country, too. You’ll never come to those clear decisions if you haven’t been immersed in that world and surrounded by a bubble of information that provides you with an understanding of the logical progression of horse training. I’m forever grateful for the time I spent at Walter Christensen’s in Germany. His theory was the old classical theory written in books. They said, training has been done this way for hundreds of years and the process is just a given.

When your training isn’t going in the right direction, you need to be able to draw on that classical, theoretical knowledge base to find a different way to explain a concept to your horse. For example, why is the horse not able to do a flying change? It might be the way you’re interacting with him or a lack of understanding on his part or maybe it’s his body mechanics. Perhaps you need to figure out how your horse can jump through in such a way that he doesn’t lose his back and his hind legs. In some cases, that has to be done in an uphill frame and in other times in a frame with a lower neck. Sometimes you just need to find another approach and go down a different road because every horse is different. That different road, for most of us, needs to be a classical road because we require that the end result always maintains and develops the gaits.

Then there’s another kind of knowledge: Horsemanship. For some riders, the fatal flaw is lack of horsemanship.

4. The Rider With Good Horsemanship

Many riders never learn about horsemanship because they didn’t spend a large part of their lives in an environment where they could learn the countless ways in which we need to watch out for our horses’ physical and emotional well-being. Being with the horse at 7 p.m. when the vet can be there is one tiny part of the endless work ethic that is required.

I recently read an article written by one of the show-jumping Leones, who said that if your breeches are still clean at the end of the day, you’re not a horseman. That’s why the Leones ride in chaps. Horsemen braid and muck. If the horse is sick or injured, they hand-walk and stay on top of the horse’s every need. At some level you have to really care about and love horses to sustain that work ethic.

Most directly, the horse’s well-being is the responsibility of the rider and it’s paramount to the horse’s ability to perform well. But to some degree, the team around the rider supports that responsibility.

When I had the opportunity to train with Dr. Uwe Schulten-Baumer, Isabell Werth’s long-time trainer, I saw that Isabell traveled with her horse to the vet. The greats that I know operate that way. The Dutch superstar of the time, Anky van Grunsven was always involved, clipping her own horse and working directly with the vet.

I was always the decision-maker regarding treatments and soundness, but when I was in the thick of things—1998 Rome World Equestrian Games (WEG), 2000 Sydney Olympic Games and 2002 Jerez WEG—I was fortunate to have a great team, including Dr. Midge Leitch and Dr. Carolyn Weinberg along with fabulous grooms, Christy Baxter and Allison Brock, all of whom worked together. We all made decisions together as a team, and that luxury takes a great weight off the rider.

5. The Emotional Aspect Of the Puzzle

In the face of resistance, lack of forwardness or whatever situation your horse presents, you have to retain your emotionally stability. Being consequent is related to our emotional way of being. Our emotions, from moment to moment shouldn’t make us inconsistent, tense, short-tempered, overdemanding, unsympathetic or feeling defeated.

Physical fear, fear of failure or fear of success needs to be dealt with by some riders.

Positive emotions need to rule your horse life. It’s important to be a person who learns from mistakes and turns failure into growth. All riders get knocked down. Even the best of the best end up in the fetal position at times. Do you learn from your mistakes and carry on as a wiser rider?

My philosophy is that you’re allowed to be in the fetal position for 24 hours and then you need to try the next approach, the new idea, and start the training from a different angle. People who succeed are always able to get something positive out of failure and they emerge from the fetal position feeling excited about the next step forward.

6. Short- and Long-term Concentration

Some people simply have too many aspects to their lives so they’re not able to commit and focus. You can’t bale hay, play the stock market, travel the world and also be able to manage and prioritize your horse life: reading up on the new rules, thinking about the feeding program, concentrating on long- and short-term goals, scheduling vet, farrier and alternative therapies, and, and, and.

Some riders have difficulty with short-term concentration when they’re riding. They exercise their horses without using their brains. They’re in their own world daydreaming, teaching or talking incessantly, and I often say that’s wasting the horse’s time. You can’t possibly be preoccupied with something or someone else and also be riding well, but riders do that all the time.

If you aim to be clear, consistent and consequent in the saddle, you have a lot to concentrate on. I remember after an important test one time, an observer said to me, “I can’t believe your horse didn’t react to that distraction.” And I said, “I didn’t even notice that.” I had no idea what was going on around me and my horse didn’t either. That’s your goal.

When you’re having a conversation with your horse and you miss a moment because you lost your concentration and you aren’t able to stay in swing with your horse, that means your horse didn’t get the message. When you’re being impacted by the outside environment or the physicality of your horse’s reactions, a lack of concentration compromises your ability to be consistent, deliberate and precise time after time, so it undermines the possibility of being consequent.

Being Consequent.

The Germans use the word “consequent” to mean that the rider is able to give her aids clearly and consistently in all situations and the horse (as a “consequence” of those clear, consistent aids) understands precisely how to react to them. To be consequent, everything you do in the saddle has to be focused, clear and consistent.

7. People Skills

Young people sometimes ask me, “How do I get my first sponsor?” If you’re out there passionately doing what you’re doing, your horse looks like a million bucks, is obviously healthy and well cared for and you’re riding well, you will be admired for that. That’s what makes someone buy a horse and put it in your care. That’s what makes a vendor want you to represent his product. But the relationship is not the result of a rider saying, “Gimme, gimme, gimme.”

It’s the same as making the Olympic team. You don’t have to set out to do it. Rather, it can be a windfall that is a result of many other qualities and events in your life. Sponsorship is a matter of having character, integrity and the ability to offer your supporters whatever they need to sustain a symbiotic relationship. Sponsorship situations that work well and last over time are a result of the rider consciously or unconsciously prioritizing and making sure the sponsor gets whatever floats his boat. The vendor obviously wants accolades. The horse owner may want any number of things. They might want to ride the horse themselves sometimes or maybe they want to sit in the VIP tent, vicariously enjoying the ride or maybe they want to be involved in the training process. Others don’t even care if the horse goes to a show, but they might want to be included in every little decision. Each owner has things that they like and you have to be sensitive enough to know and give back whatever that is.

Sometimes it’s not possible because what the sponsor wants doesn’t mesh with your way or your abilities. A sponsor might want instant gratification, more ribbons and accolades, and that’s not your way. You can absolutely end up in a situation in which the motivation of the sponsor doesn’t fit with who you are. But some riders are simply insensitive to the sponsors’ needs or they often aren’t good at communicating. The symbiotic aspect of the relationship is really important to its longevity and it requires a strong commitment and lots of work as any relationship does.

People skills with clients are important for the rider who earns a living teaching and coaching. Teaching styles, at their worst, can be demeaning or belittling toward the student because the teacher isn’t a big enough person to want to give away the knowledge or he doesn’t get joy out of helping riders and seeing their success. It’s important for riders to know that a problem isn’t always their fault.

I often watched Dr. Shulten-Baumer teach Isabell. He never rode, but he provided objective feedback with the constant goal of perfection regarding the shape of the horse, his movement and the execution of exercises. He provided the voice of reason when the situation wasn’t ideal. He might simply say, “The horse is too short in the neck.” Or if something wasn’t working one day, he might point out that the horse had had the previous day off, and he would assure Isabell that the work would be easier for the horse tomorrow. That simple, objective feedback from a trainer is vital.

The above categories don’t each exist on an island. There’s overlap, and perhaps you can think of other desirable qualities, but the fact remains that to be a successful international rider or at least one of great accomplishment, you need to have all these attributes. If you fall short (as most riders do), you need to be willing to do whatever it takes to assimilate the full skill set and tend to all the details within each piece of the puzzle. That means long hours and missed social engagements. And it’s hard to work on some of these pieces.

I know some riders who have worked hard but were missing one of the little pieces, so success at the highest level didn’t happen for them. I know other riders who have taken ownership and made a long-term commitment to working on each of these pieces and they have each found extraordinary success.

Next month, I’d like to take a practical look at how you can utilize some of these attributes as you teach your horse a few standard dressage movements.

To read more articles with Sue Blinks, click here.

Sue Blinks started her dressage education growing up in Rochester, Minnesota, with Marianne Ludwig. She then spent two years working with Walter Christensen in Germany. She was a member of the U.S. dressage team at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games, where they won team bronze, the silver-medal team in Jerez in 1998 and again represented the U.S. in the Rome World Equestrian Games in 2002, riding Flim Flam, owned by Fritz Kundrun. During that time, she trained with Dr. Uwe Schulten-Baumer and Isabell Werth. She also rode with U.S. coach Klaus Balkenhol leading up to the Games in Jerez. In 2004, Sue began riding Louise and Doug Leatherdale’s horses and currently rides Habanero (His Highness), owned by Louise Leatherdale. Sue lives in Wellington, Florida, and Columbia, Connecticut.