Colic. Perhaps no other word strikes more fear in the heart of horsemen and -women than this painful condition, which can strike at any time and often seemingly without cause. It is indiscriminate and can even prove fatal for any equine, from international dressage stars such as Warum Nicht, Harmony’s Mythilus and Kingston to beloved backyard companions—and magnifying the fear is how little we really know about it. So with the demands of modern-day horsekeeping, training and competition, how can dressage riders and owners help protect their steeds from becoming colic’s next victim?

Know Your Enemy

Colic is ranked as the No. 1 medical cause of death in horses. But it’s important to remember that colic is not a disease. It is the horse’s physical manifestation of abdominal pain, and this discomfort can be caused by a dizzying array of conditions, from a minor excess of gas to a deadly intestinal twist. “In reality the list of possible pathological conditions that can give rise to colic reads like a laundry list,” said Patrick Warczak, Jr., vice president of marketing for Freedom Health LLC. “According to a presentation given by Dr. Nathaniel White to the American Association of Equine Practitioners [AAEP], more than 80 percent of colic cases are considered to be idiopathic, meaning that they are of unknown origin. In addition, 10 to 15 percent of episodes are repeat cases. That doesn’t necessarily mean that the veterinarian doesn’t have an idea of the cause; what it means is that what would need to be done in order to confirm the exact cause is not performed, not possible, or not worth pursuing due to circumstances or cost. Most colics are treated as a medical case, meaning that the vet comes to the farm, treats the horse and he pulls through; but a certain percentage of cases do go on to be surgical and, unfortunately, some are fatal.”

“The fact that we have not been able to figure out how to completely prevent colic is disappointing, but the good news is that we have scientists all over the world studying what causes colic in horses and what can be done about it,” added Dr. Lydia Gray, staff veterinarian and medical director for SmartPak®. “Being aware of risk factors and making smart management choices is one of the most impactful ways for horse owners, barn managers and trainers to help reduce the risk of colic in horses under their care.”

With more than 40 years in private veterinary practice, Richard D. Mitchell, DVM, MRCVS, Dipl ACVSMR, of Fairfield Equine Associates in Newtown, Connecticut, reports a noticeable decrease in both the number of colic cases as well as colic surgeries he’s seen in his practice. “I believe this is due to the fact that horses are managed better than they used to be,” said Dr. Mitchell. “For instance, before ivermectin came on the market we saw colics due to large-strongyle infestations, which we don’t see much anymore thanks to effective deworming programs. In general, I think owners of high-performance sport horses better understand colic risk factors, but at the same time I think people do get complacent with the care of their horses and perhaps don’t think about colic as much as they should. It’s not always one major definitive episode. It can result from a cumulative effect of small factors which can be hard to put your finger on, so it’s possible for mild symptoms to escape people until it becomes a much more serious issue over time.”

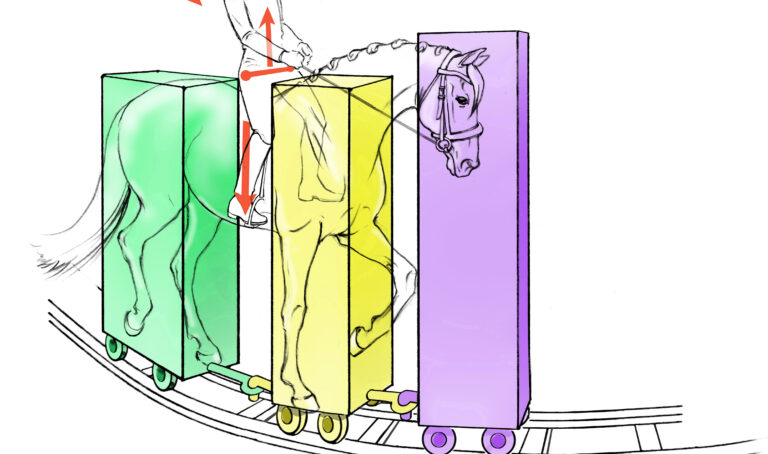

Dr. Mitchell believes the top three causes of colic in dressage horses are travel stress and subsequent dehydration; abnormal gut motility, possibly secondary to chronic gastrointestinal ulceration or inflammation; and lack of activity and grazing. “I think lack of activity is a major factor, mainly coming from restricted turnout, which is common among high-performance equine athletes due to fears that they will hurt themselves in the pasture,” he explained. “So if they can’t be turned out, you’ve got to find another way to get the horse out of the stall several times a day in addition to his regular work schedule.”

The Stress of Showing

This summer Dr. Mitchell traveled to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, for his sixth Olympic Games as a U.S. team veterinarian, this time for the bronze-medal-winning U.S. dressage squad. Throughout the arduous journey and intense competition, preventing colic was a top concern and Dr. Mitchell took a proactive approach to help ensure the horses’ well-being.

“I recommended that all the horses receive a double preventive dose of anti-ulcer medication to help protect their gut,” he explained. “We fed them several times a day in small amounts and tried to maintain their schedules as closely as possible to avoid disruptions. I also liked the slow-feeder hay nets, where the horse is constantly eating and salivating, better mimicking a natural grazing behavior.

“In addition, we were very careful that, before the horses ever got on a plane, they were extremely well-hydrated,” he continued. “That may or may not have included using intravenous fluids, but in most cases it didn’t. We were able to give them multiple meals that included an extra dose of electrolytes in mash form because the most efficient way to get moisture in their system is orally. And because lack of movement, such as on a long plane ride, leads to lack of gut motility, as soon as we could we got them out of the plane or off the van and walking around to help get things moving again.”

But one doesn’t have to be competing in the Olympics to be concerned about colic. Even the stress of participating in a local schooling show can have its risks, and Mary Alice Malone of Iron Spring Farm in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, takes a proactive approach. Iron Spring Farm suffered its own tragic loss when renowned Friesian stallion Heinse 354 succumbed to colic in 2009. “You can’t prevent every episode of colic, but you can make your horse’s environment as conducive to health and well-being as possible both at home and on the road,” she explained. “At the shows, always notice the details. Get your horse out to walk and graze. Take his temperature and monitor his manure. Is it runny or too firm? More frequent than normal or less frequent? Also, ask yourself Has my horse had a hard day at the show?Was the footing hard? Do his feet hurt? Extra stress can bring on a colic episode. It’s also really important to have a night-check person. Most shows offer horse-watch services with great people. Take advantage of this resource and spend time talking to them about your horse.”

Malone agrees with Dr. Mitchell that keeping horses hydrated is extremely important. “The horses at Iron Spring Farm always drink from buckets both at home and on the road so their water intake can be easily monitored,” she noted. “Some people wet the hay to help increase hydration. Sometimes horses don’t like the taste of the water at a show venue and you need to encourage them to drink more, so one idea is to add low-sugar Gatorade to the water. But you have to know ahead of time whether or not they like the flavor of Gatorade because if they don’t, you’re defeating the purpose. Hydration is also extremely important when you ship horses. Proactive measures might include extra electrolytes or giving them small amounts of mineral oil, but be sure to discuss these plans with your veterinarian.”

A Biological Accident

Even under the best of care and circumstances and with every possible prevention taken, colic can still strike with no good explanation of cause. During the Aachen CHIO in Germany this July, U.S. dressage team member Katherine Bateson-Chandler’s mount, Alcazar, suffered a colic episode after a lackluster performance in the Grand Prix test. Despite immediate veterinary attention, he was eventually transported to a nearby clinic for successful colic surgery, and the Dutch Warmblood gelding continues to recover.

“As evidenced by this and so many other cases, no matter what you do, colic can still happen. The best way I can describe it is as a ‘biological accident,’” said Dr. Mitchell. “It can be a culmination of small factors that by themselves would not trigger a colic episode, but when they all come together they will cause it. For instance, decreased gut motility and a reduction of water intake during a long van ride can possibly predispose a horse to have a displacement or a twist. Or maybe a stretch of hot weather changes dramatically to cool off so the horse doesn’t drink quite as much as usual. Or ulcers flare up at a show due to the stress of competition, resulting in colic symptoms. It can be nearly impossible to pin all that down.”

Regardless of the cause, one universal truth prevails: Don’t delay in taking colic seriously. “You can’t be dismissive of what the horse is trying to say to you,” Dr. Mitchell emphasized. “You have to get right on it—don’t ignore a symptom and hope it will go away on its own. It’s the worst thing you can do because you never know when a situation can be potentially fatal.”

Malone agreed. “Colic is an incredibly scary thing, but you’ve got to catch it early,” she said. “The better you know your horse, the more quickly you will notice if something’s not quite right. Be observant, especially at a show. Horses don’t always paw or thrash to let you know they’re not feeling great. They might simply have a funny look on their face or curl their lip or not eat their carrots. If you suspect something, check respiration and heart rate if you know how, but don’t try to be your own veterinarian—get help as soon as you can.”

Dr. Mitchell knows from experience that taking action sooner rather than later can make the difference between life and death in some colic situations. But before you reach for the medicine when your horse starts pawing, pick up the phone instead. “Make sure to talk to your vet before giving any Banamine. I know it’s common practice to give Banamine and it’s a wonderful drug for colic, but I never recommend giving more than 5cc before the vet arrives. Overmedicating the horse before the vet has seen him is bad news. You may think you’re helping, but in reality it just ties the vet’s hands in trying to accurately evaluate your horse,” said Dr. Mitchell. “Despite good intentions and no matter what your budget is, you’re better off spending the money to get your vet involved right off the bat and make sure the horse is OK early on rather than waiting and have the horse’s condition be compromised by lack of action.”

Save