A pivotal moment in my dressage career happened when I was about 13 years old. I had been hired to halter break a yearling filly so I could braid her for her breed inspection. The owner had succeeded in haltering this filly once in a cartoon-like episode that involved both horse and human scrambling in circles around and up and down the walls of a stall. I was dreading the replay.

My mentor, Charles de Kunffy, has always taught me to create a situation in which the horse does what you want. So I began making friends with the filly by scratching her on the withers. I showed her the halter and held it out in front of her. I remained near the doorway of her stall the whole time, so that she could come to me or ignore me if she chose. Every time she approached and moved her head close to the halter, I scratched and praised her. Every time she moved away from the halter, I did nothing. I didn’t discipline or pursue her … I just did nothing. After 20 minutes of playing this game, the filly shoved her head into the halter. Her enthusiasm thrilled me. At that moment, I knew this was the way I wanted to train my horses.

The ultimate goal of dressage is the development of the horse into a happy athlete through harmonious education. As a result, the horse is calm, supple, loose and flexible. Because of this, he gains confidence and is attentive and keen.

As dressage riders and trainers, we can teach our horses to enjoy learning. I loved it when the Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) introduced the concept of developing the dressage horse as “a happy athlete.” It reinforced that pivotal moment in my childhood, and I have looked for ways to train my horses to be happy athletes ever since. I have been fortunate to learn methods from many truly great horsemen. In this article, I would like to share some of these important concepts with you.

Motivate Your Horse with Praise

I use praise a lot in my training. Horses become a lot more excited and interested in their work if you “throw them a party” when they make a big effort to do something right. Horses seek approval, and they really respond when your positive energy communicates to them: That’s right; you are on the right track. Remember, horses are herd animals and you are like the boss mare to them. As boss mare, your approval means a lot.

For your horse to make an association between his actions and your approval, praise has to be given at the same instant. You can praise your horse in the moment with your voice or simply by relaxing your aids and moving in harmony. Other rewards, such as stroking the neck, giving sugar or taking a break, are harder to make coincide with a desired behavior, but they can still be used to make training a positive experience for your horse.

When training, it’s really important to give the horse recognition for trying, rather than holding out until the final product is perfect. When I teach clinics, I notice that riders often wait too long to give praise, or they expect too much too soon. They want the whole movement to be perfect before they will reward their horses. I love the saying: Ask much, expect little, praise often.

For example, let’s say you are working on developing a pirouette canter. You collect the canter and the horse gives you two of his best steps of pirouette canter ever, but then he breaks into the trot. Do you smack him with the whip because he made a mistake? No, that sends the wrong message. In this situation, I would praise the horse with my voice as he was making the good steps. After he broke, I would quietly bring him to a halt to recover his balance, and then I would ask him to canter again. I would go back to the exact same place where the mistake happened and ask for the pirouette steps again. This time I would pay closer attention to how effectively I am coaching him with my aids. This way, he feels encouraged, as if I told him, “Let us try once more, because you are really close!”

If you have ever learned to speak a foreign language by conversing with a native speaker, you can understand how the horse feels. If the native speaker is patient and encouraging when you almost get the words right, you keep trying. If that person becomes frustrated with you, or raises his voice to “get through to you” when you do not understand, you might feel discouraged about your ability to learn and hesitate to keep trying.

How to Approach Training Challenges

Are you thinking, All that sounds great, but what do you do when you have a training problem? First, I identify the main problem by asking myself, for example, is the horse tense, is he evading the work, is he not mentally understanding, is he not physically strong enough or are the aids confusing him?

Sometimes it is hard to decipher what is mental resistance and what is physical. Scott Hassler has really helped me understand that mental tension can often be effectively soothed when treated as if it is physical. In other words, the easiest way to reach your horse’s mind is through his body. By incorporating circles and lateral movements, you can loosen your horse’s body, and the tension in his mind will diminish at the same time. When your horse yields to your leg with a supple rib cage, he lets go in his body and his mind.

Let’s consider the horse who is evading the work. Horses express this type of resistance in three basic ways: speed, inversion and crookedness. Some evade by rushing and ignoring half halts, while others may be sluggish and behind the leg. Inversion problems are expressed as going behind the vertical, going behind the bit, going above the bit and dropping the base of the neck. Crookedness can be expressed in a zillion ways, but the most common is the horse who falls out with his right shoulder and hangs on the left rein. If you don’t address these types of evasions, they will grow, and they will grow faster when you add excitement, such as at shows or clinics. Recognize them when they are small, and it will be easier to nip them in the bud.

Horses can also seem resistant when the rider is vague or inconsistent about expectations. For example, if you allow your horse to walk off from the mounting block when you are barely in the saddle half the time and then yank on the reins and scold him the other half, he is bound to be confused and frustrated. Horses, like children, need consistency and structure.

There may be a time when your horse will benefit from an outside professional to help get you through a training issue. A professional trainer can help make things more clear to your horse. Also, make sure your horse is in good physical health, as pain can also be a source of training resistances.

The horse should never feel like you are the one causing his problem. In fact, when he solves his problem, you need to be the first one to cheer his success. To train this way, you have to be smarter, not stronger. Think of yourself as being like a soccer coach or calculus teacher—the work is challenging, but you are there to guide him through it.

Find Ways to Help Your Horse

The horse who does not mentally understand needs you to break the exercise down to its elements for him. When you encounter problems in your daily training, it’s a cop-out to yank on the inside rein or smack the horse with a whip with a “do it” attitude. Slow down, stop if you must and think through: Why is this happening, or why is what I want not happening? How can I better explain this to my horse?

For example, if you are having trouble with flying changes that are late behind, repeating the late change over and over won’t help at all. You have to think through why the change is not successful. Some of the elements you might examine are the quality of the canter, the prompt reaction (or lack thereof) to your leg aids, his straightness or his engagement before the change. Once you have identified the weak link, choose an exercise to help your horse understand. For example, you probably have an engagement problem if your horse is speeding and/or falls on the forehand in anticipation of the change. You can improve his balance before the change by improving his response to your half halt.

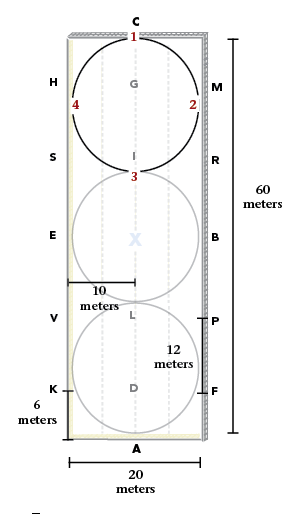

Gyula Dallos taught me this super exercise for improving the half halt. Ride along the track of the arena. At each letter, ride a volte (you can vary the size from 8 to 12 meters to suit your horse’s level of training). As you approach the rail or wall at the end of your circle, make a downward transition. Make an upward transition, continue along the rail to your next letter, and repeat the exercise. The small circles will show your horse how to collect himself. A downward transition when approaching the rail or wall makes sense to a horse, and yours will begin to engage in anticipation of a transition. Your light, correct aids can simply accompany that shift in momentum. This whole exercise circumvents your having to pull too much on the reins, which blocks the hind legs and is unpleasant for the horse. This exercise can be ridden at trot or canter. You can start with trot–walk transitions and progress to canter–trot, canter-to-walk and trot–halt transitions. The exercise benefits your horse mentally and physically, as he learns to half halt from a light aid while building his strength with the circles and through the transitions.

Don’t be afraid to get creative with your training if it helps your horse understand. Here is an example: I once trained a talented mare who had a trot with little natural loft. She could piaffe easily, but she didn’t get passage at all. Fortunately she loved to trot over ground poles, so I gradually raised and shortened the distance of her cavalletti. I did it gradually to build her confidence. She discovered that she could navigate the poles by putting more lift into her strides. I added the aids for passage coincidentally, so that she began to associate my aids with that feeling of extra suspension in the trot. Eventually she offered passage whenever she felt my familiar aids. She learned the feeling of adding expression to her trot through her muscles first, and then she believed it in her mind. I could have kicked and pulled on her to try to make her passage, but until she felt it in her body first, she had no idea it was possible.

Cross-Train for Fun

Cross-training makes work into a game for the horses. Their natural enthusiasm for playing makes building muscles easy. Cavalletti exercises are a great start for cross-training, but don’t stop there. Schooling out in the fields, galloping on a track, trail riding, free jumping and gymnastics (jumping small jumps) are all great ways to refresh your horse. While you should avoid dangerous footing, exercise over uneven ground and slopes is good for improving the resilience of muscles and tendons. You can also ride out with friends. We had a filly who did not like to go forward, so we hacked her out with another horse and let them take turns playing follow the leader. It quickly became her idea to go merrily forward.

When my young horse Donnermuth qualified to compete in the 6-year-old test at the World Breeding Federation for Sport Horses Championships in Germany, I had to find a way to prepare for the pressures of international competition while preserving his youthful enthusiasm. By taking most of our schooling sessions out to the fields, I was able to keep the work playful. I did the same thing with Fiji when I was preparing him for the Young Horse Finals in Chicago. The deep grass taught him to really bend his joints, and it got him in the habit of moving with a lot of expression.

When I do cavalletti work with my horses, I prefer poles that are lifted off the ground so they cannot roll, and so the horse has to make an extra effort to get over them. When riding over cavalletti, sit lightly and allow the horse to lower his neck in order to make full use of his topline. Keep your hands low and light, while your upper body remains in balance with the horse. Ride through the middle of the poles and maintain the same tempo.

Here is one of my favorite cavalletti exercises: The trot–canter–trot transition may seem easy, but, like I tell my students, there is a reason it is still in the Grand Prix test. When this transition is done right, it proves that the horse is loose and swinging in his back, truly on the aids and understanding your seat bones correctly. Here is how I do it: I set up three to four poles on a 20-meter circle, fanned so they are at about 4 feet 3 inches apart at the center (I estimate this with five heel-to-toe footsteps). I trot my horse over the poles and then depart in canter after the poles. Then about 10 to 15 meters out, I drop back down to the trot and ride over the cavalletti again. This is a wonderful little exercise for developing coordination, reaction to aids and thoroughness for both horse and rider.

Master Your Seat

The rider, who sits in a quiet balance while giving crystal clear aids, creates a confident horse. If you want to be a fair and effective rider, a good seat is crucial. All the classic dressage books were written with the assumption that the reader was already a rider with an independent seat, but we must not take this good seat for granted. The development of a deep and adhesive seat takes a lot of self-discipline.

We often talk about how many years it takes to train a horse to Grand Prix, but what about us? Just as we develop the horse’s muscles, we too must train to be Grand Prix riders. If we want to be more effective, we need to dedicate time off our horses to learn to carry ourselves better within our own bodies. Body awareness, control, flexibility and strength will not come overnight. Just like with the horses, gradual and pragmatic practice make all the difference.

The good rider rides from the inside out. This requires a strong, stable core. The more stability you have inside, the more precise and fluid you can be with your legs and hands. Riders who don’t have core stability have to use much stronger aids. They have to direct a lot of energy at the horse. These riders may feel frustrated because they feel like they have to jerk the horse around to get through to him. Develop true balance from the inside of your body so that you can be in harmony with your horse.

Having a good seat also means that you don’t give aids inadvertently. For example, if you shift your weight to the inside, the horse should respond by moving under your weight. If you always sit to the inside, then you have to apply rein and leg aids to override your horse’s effort to turn in. Imagine how agitating this must be for the horse who is sensitive enough to be annoyed by a fly.

How can you improve your seat? Seek out instructors who will take the time to instruct you on the correct position. Invest time in longe lessons. Ride without stirrups whenever possible. Even to this day, I ride without stirrups on a weekly basis. Take turns videoing with your friends. Outside the arena, make the effort to participate in pilates and/or yoga classes. I ride horses all day, but I still make time to work out and do yoga on a regular schedule.

Master Yourself

The proud dressage horse is a joy to watch. Horses develop that kind of sparkle when nurtured with fair, positive and consistent training. For the trainer, this requires tremendous self-discipline. Anger, frustration, impatience have no place in dressage training. I see a lot of dressage riders get into trouble when they become obsessed with, “I gotta get this,” or worse, “I gotta perfect this.” Both Steffen Peters and Charles de Kunffy taught me this wise training tip: What you don’t get in 30 minutes is for tomorrow.

Dressage training was originally reserved for military men and young aristocrats. To learn to ride, they had to learn to control themselves physically and mentally. The horses taught future rulers that you must be able to rule yourself before you can rule others. Today dressage offers us the same valuable lessons. Self-analysis and self-control are crucial when it comes to creating a harmonious relationship with a horse.

As an equestrian, you have dedicated your life to the wellbeing of a horse. It’s the responsibility that comes with being a rider. Love your horse enough to learn to ride him well. Horsemanship has to come back to being our main objective. We were lucky to have Steffen Peters and Ravel as an example of what is possible. This harmonious pair came to the top of our sport. Despite the pressures of world travel and international competition, Ravel radiated relaxation, confidence, contentment and exuberance all at once—the ideal happy athlete.

This article has been modified from its original version that first appeared in the January 2012 issue of Dressage Today.

Jessica Jo “JJ” Tate is a U.S. Dressage Federation (USDF) bronze, silver and gold medalist. She represented the United States in the 2007 FEI World Breeding Championships for Young Dressage Horses in Verden, Germany. Tate was also a World Cup finalist and was long-listed for the World Equestrian Games in 2006. She is on the U.S. Equestrian Federation’s (USEF) Developing Riders List.