Totilas, an elegant black stallion born in Friesland, the Netherlands, in 2000, was destined to become a famous and controversial dressage horse. Jan Schuil, the Dutch veterinarian who bred him, knew early on Totilas was special: the floating walk, the defining self-confidence tempered with unexpected sweetness. Early in his life, Totilas was ridden by Jiska van der Akker, a Dutch rider who was paid 15 Euros to ride him three times a week, counting on his sale to make the investment of her time worthwhile. Eventually, he was discovered by Edward Gal, the celebrated Dutch rider who rode with a softness that seemed innately suited to Totilas. Gal persuaded Kees and Tosca Vissers, Dutch billionaires, to invest in the purchase of Totilas.

In 2009, Gal and Totilas competed at the European Dressage Championships in London. Commentators said: “Totilas is magical. He doesn’t look real.” In 2010, Gal and Totilas produced another record-breaking score, this time at the World Equestrian Games in Kentucky. Twenty-two thousand fans watched their performance. Commentators said: “He’s the horse of the century.”

Shortly thereafter, with or without Gal’s knowledge, the Vissers agreed to sell Totilas to legendary German horse breeder and businessman Paul Schockemöhle and German heiress and dressage Olympic medalist Ann-Kathrin Linsenoff. Linsenhoff’s stepson, young German rider Matthias Rath, took over the ride on Totilas and later that year, Rath and Totilas performed at the World Championships in Holland. The stallion appeared resistant, unhappy. This time, commentators said: “He’s not the same horse.”

Captivated? You’re not even halfway through “The Story of Totilas,” a documentary by award-winning Dutch filmmaker Annette van Trigt.

Over a staticky international phone connection, van Trigt explains: “I love the challenge of a difficult story, the one that’s hard to get inside. As a filmmaker, I’m trying to access the most impossible stories in the horse world.”

Based out of the Netherlands, van Trigt is comfortable in the spotlight: She’s been a Dutch television and radio personality since 1985, covering national and international sporting events. In Holland, virtually everyone knows her name, face and voice. About 10 years ago, van Trigt realized that despite her celebrity status and success, she had essentially been working the same job for a long time. In a way, she just got bored. At that point, she founded her own production company. Soon after, van Trigt was riding her own horse, a KWPN named Vinnie, across a field when she realized she wanted to produce a documentary about Totilas. She says, “I asked myself, what happened to this amazing horse? He was just so special.”

The resulting documentary is “The Story of Totilas,” for which van Trigt was awarded Best Director for International Documentary and Best of Festival for International Documentary Over 60 Minutes by the EQUUS Film Festival (EFF) in 2017. According to van Trigt, the first version of the film was 60 minutes long and aired nationally on Holland’s public service television in 2014. Van Trigt says, “Even people that didn’t have anything to do with horses watched. They started the film not intending to finish, but then couldn’t stop watching—1.2 million people watched within two days. For a documentary, this only happens two or three times a year.”

As Totilas’ story seemed far from over in 2014, van Trigt (and her viewers) wondered what would happen next. So she followed the story for two more years. In 2016, she completed “The Story of Totilas.” The 80-minute film was broadcast on commercial, local and regional channels in the Netherlands and is also currently screened by Ziggo Sport, a membership sports channel.

Van Trigt’s film is riveting in part because she secures exceptional access to most of the major players in Totilas’ story. Gaining access took time, patience and persistence, as many of those involved did not want to speak about Totilas. As a TV journalist, van Trigt had unique access to major sporting events, such as the World Equestrian Festival in Aachen, Germany. Attending these events, she repeatedly approached those involved with Totilas. Eventually, her personal approach and persistence paid off. Though Gal never agreed to speak with her, van Trigt was granted interviews with Schuil, van der Akker, Linsenhoff, Schockemöhle, Rath and many others who knew or cared for Totilas. With her camera, she visited the farm in Friesland where Totilas was born, Linsenhoff’s estate and Gal’s training barn where “Toto Jr.” now lives.

“The Story of Totilas” explores central themes relatable to almost everyone involved with sport horses: a love for horses conflicting with financial realities; passion for equestrian sport conflicting with the horse’s best interest; skill and talent in the saddle going only so far when confronted against wealth and power. And, the horse is not a machine: What he’ll perform for one, he might not perform for all. According to van Trigt, “This is a story about a horse, yes. But it’s also a story about people who are too eager to earn money lying and hiding. In the end everyone who has had something to do with Totilas is left unhappy. Everyone had his agenda and no one put the horse first. The German journalists say the horse became a mirror of the humans in this situation.”

Van Trigt’s film masterfully weaves the perspectives of the many humans touched by this “horse of the century,” capturing every viewpoint from the breeder who never intended to sell, to the rider whose heart may have been broken, to the fans who watched and wondered about the fate of Totilas.

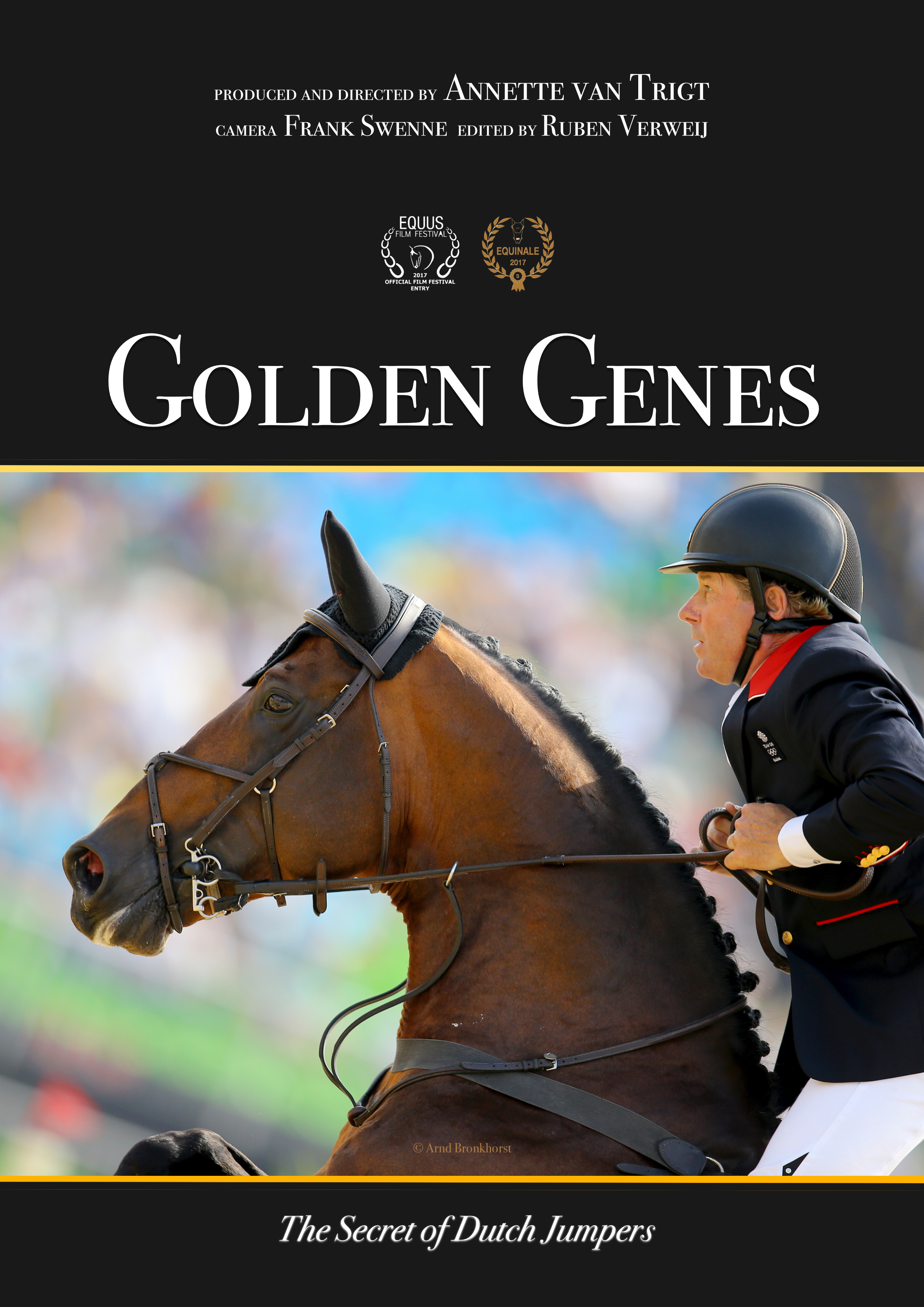

“The Story of Totilas” is just one of van Trigt’s documentaries about the horse world. She has also produced/directed “Amish 2.0” and “Golden Genes,” both of which were also EFF finalists in 2017. It seems unexpected that a Dutch filmmaker would take interest in the Amish community of Grabill, Indiana. Van Trigt explains: “I’m looking for big stories. At an event I met Wim Cazemier, a breeder of Dutch Harness Horses (DHH) who decided to go to America to sell his horses to the Amish. When I heard this, I thought, ‘This is the way for me to enter the Amish world.’ So I started researching. I sent another journalist with whom I work to the U.S. with Wim, along with a small camera, to see what was going on. One year later, with permission from the Amish, I hired my cameraman and we went to follow them for two weeks.” Van Trigt had to overcome a major obstacle to make this film: Namely, traditional Amish beliefs forbid photography. However, the more progressive Amish gave her permission to film so long as the focus of the film was on the horses and most of the humans were captured only from the back.

(Courtesy, EQUUS Film Festival)

The film highlights the intersection of two cultures: DHH breeders from the Netherlands and the Amish from the American Midwest. They meet because of their shared admiration for the DHH and mutual understanding of horse breeding as an agricultural business. Cazemier finds opportunity in the U.S. by selling, training, showing and advising on DHH, while his Amish acquaintances express deep appreciation for the breeding, appearance and ability of these horses. They purchase and import approved stallions and stand them at stud in the U.S. Djoe Zher and Lester Graber, Amish co-owners of the imported stallion Colonist, explain the delight in owning a horse like this. Not only does Colonist stand at stud and bring income, he’s also in effect a status symbol in the Amish community because of his great looks, action and sensitivity when driven. At times, Zher and Graber have encountered difficulty with church officials who consider this horse “too luxurious” for the Amish community, where religious beliefs discourage individualism and flashy material possessions. (Compared to the average plain buggy horse, Colonist in harness is the Amish Porsche.)

The film highlights the story of Patijn, one of the first DHH stallions imported from the Netherlands to Grabill, Indiana. Roelof Harm Veenstra was the Dutch breeder who had previously owned Patijn. Veenstra tells the camera he never intended to sell this horse, but an American buyer who was in the Netherlands on behalf of the Amish persisted. Veenstra receives an offer, then a better one and finally one that he felt he could not refuse. As in “The Story of Totilas,” van Trigt brings the viewer close to the perspective of a breeder who is invested in his horse, both financially and emotionally. Van Trigt says, “I want the viewer to ask herself: What would I do? Let’s say you’re this breeder. Would you sell?”

The Amish tendency to avoid cameras led to at least one culture clash. After van Trigt and her cameraman had completed two weeks of filming, one of the Amish who had willingly participated in interviews called her at her hotel. He said, “Just so you know, we’ve allowed you here with your camera, but it was never our intention that you should broadcast any of the footage.” Van Trigt had to let him know that the footage would indeed be broadcast—after all, what was the point of them filming otherwise?

People like to talk, van Trigt explains. From day one, she informs them of her intention to produce a documentary—that’s the reason she’s investing time, money and energy in the filming. But then, like the Amish breeder, subjects sometimes see the press release about the film or realize for some other reason the broader implications of having their stories broadcast. This reality check can cause panic and they want to back out, but van Trigt persists with telling the stories she’s worked hard to gather. She says, “I love this life. It’s interesting and when things go well, it’s great. I can utilize my access, experience and platform to get unusual flavor.”

“Golden Genes,” a third van Trigt documentary, opens with gorgeous footage of KWPN broodmares and foals. This film again brings us close to where KWPN greatness originates: the breeders. “Golden Genes” asks the question: What is the Dutch breeders’ secret to success? Van Trigt interviews breeders including Wiepke van de Lageweg, who bred and stood the great Nimmerdor, and Cees Klaver, who bred world-class show jumpers Taloubet and Big Star. She asks breeder Peter Rinkes why the Dutch are so good at breeding horses. Rinkes replies: “We’re also good at breeding pigeons and rabbits.” He’s referencing Holland’s deep agricultural roots, the Dutch knack for business and the breeders’ progressive approach. As in “The Story of Totilas” and “Amish 2.0,” viewers find themselves confronted with questions about what determines the value of a horse to the breeder and to others.

Lisa Diersen, EFF’s founder, comments on van Trigt’s exceptional ability to engage the audience with her stories. “Annette seems to make the people she interviews feel so comfortable,” Diersen says. “Somehow she invites you as the viewer to enter their stories.” EFF travels around the country, showcasing more than 80 films throughout the year. The festival was at the FEI World Equestrian Games at the Tryon International Equestrian Center in September, screening all three of van Trigt’s documentaries.

Diersen says, “No matter where I show Annette’s documentaries, audiences are riveted by them. They play like exciting feature films, which is really rare for documentaries.” It’s van Trigt’s perspective—as a lover of sport and a lover of the horse—that brings us right to the point where human drives (to compete, to earn money, but also to deeply love a horse) meet and conflict and sometimes get messy. As a brave and experienced journalist, she does not shy away.