Ninety-five-degree temperatures were no match for the 16 young riders who rode in California FEI rider and trainer Sarah Lockman’s free dressage clinic this past June. Demonstrating the discipline’s broad applicability, Lockman shared fundamentals with pairs ranging from a 12-year-old Beginner Novice eventer and her 16-year-old Quarter Horse/Morgan cross to an 18-year-old rider on a hot 8-year-old off-the-track Thoroughbred.

A “B” Pony Club graduate herself, Lockman staged the clinic to give back to the sport. “I was a total Pony Club nerd,” she recalls. “I was a member of the Reno High Sierra Pony Club and the Silver State Pony Club for years, and I remember studying for hours every night. I took it all to heart and I think that the things I learned are one of the reasons I’ve become successful.”

Since moving to a new facility in Southern California’s Orange County in 2015, Lockman has built her business to a nearly 60-horse program. Along with developing and campaigning several horses to various levels, the USDF bronze, silver and gold medalist coached 15 horse-and-rider combinations to spots in the California Dressage Society/USDF Region 7 Championships in 2016.

Transitions between and within gaits, developing and maintaining a supple and engaged frame and working toward constant connection and quick and sustained reactions to the aids were common themes for most of the pairs in her clinic, no matter their experience, abilities and goals. Patience and dedication for the daily work of dressage was an underlying theme of the day.

The riders were also treated to lunch and goodie bags, a presentation on equine nutrition and a freestyle demonstration by Lockman’s longtime student Jenny Wetterau.

What is Pony Club?

Teaching thorough horsemanship through progressive levels of instruction in horse care, knowledge and riding skills is the United States Pony Club’s mission. The process starts at “D-1” certification—referred to as a “rating” in the past—and continues to A, a rare certification of horse-management know-how and/or riding skills that is as hard to earn as it is highly regarded.

Although it’s a great foundation for all types of riding, Pony Club is often most associated with eventing. An evolution about 10 years ago saw Pony Club add educational tracks in dressage and many other disciplines. It also added “Riding Centers” that can be operated by a professional using horses in his or her stable, rather than requiring members to have their own horse or access to one. Last, but not least, it’s not about ponies! Pony Club has always welcomed members with horses or ponies.

Pony Club originated in England, and the United States Pony Club started in 1954. Today, there are approximately 600 clubs or centers. To learn more or find one (or start one!) near you, visit ponyclub.org.

Training Highlights

Getting her 17.2-hand horse, Banner, into a better frame in the canter was one of Dana Baroldi’s goals for her session. Banner’s naturally uphill build “is great for dressage,” Lockman noted, but he needed to bring his head and neck down to create a rounder frame. That step is extra important for big horses to keep them balanced and engaged and often it’s more difficult to attain, she explained. “On a daily basis, you need to work on getting him round and through.”

Lockman said Baroldi would achieve her canter goals by starting with the trot, a less powerful gait that makes it easier for the rider to communicate what she wants—but not a “middle of nowhere trot” or a trot of Banner’s choosing, Lockman clarified. Using inside rein to establish an inside bend and a holding outside rein to bring Banner’s head down, Baroldi worked to regulate the naturally forward horse to a rhythm and degree of engagement that she dictated. “If you let him change the rhythm, he’s changing you,” Lockman advised in a theme that recurred through the day. The rider sets the rhythm, pace, track, etc., and the horse should maintain it until a cue to do otherwise is given, she stressed. That obedience is tested with frequent gives of the rein to make sure, in Banner’s case, that the inside bend or lowered head position is maintained without the rein pressure. If so, give a quick pat—ideally on the withers or neck on the inside. If not, reset the aids.

“It’s important to be picky,” Lockman explained. “It might feel mean to be so picky, but horses are herd animals. When we tell them exactly what we want, it brings them comfort.” Exaggeration is sometimes an appropriate training tool. Lockman told Baroldi to create more bend and a lower head set “than what might feel right” as a step toward developing the ideal balanced frame in the next phases of training.

With such a big, strong horse, Baroldi needed a strong core and her fingers closed firmly on the reins to deliver and maintain firm aids. “Your horse has lots of forward and you just need to control it,” said Lockman. When Banner’s trot frame was ready for canter, Lockman offered a little trick to help minimize the “woo-hoo” factor that most riders—and hence, their horses—experience when anticipating the canter. Baroldi and Banner had done several trot–halt transitions, “which is the same preparation as for canter” (encouraging the hindquarters to gather underneath by sinking down into the saddle and leaning slightly back, coupled with a holding rein). While trotting on a 20-meter circle, “you’re going to say ‘halt’ with your body, but, instead, when you feel like you’ll get a good canter, ask for it.” To counter his tendency “to get race-horsey” at the canter, Lockman told Baroldi to go for “the most slow, boring canter.” While these exercises might seem mundane, they were among several examples of exercises that, when repeated correctly and consistently, lead to brilliance in a dressage pair, Lockman stressed.

Fifteen-year-old Sarah Piferi, a member of the Royal Riders Pony Club, came to the clinic with a new horse, the Dutch Warmblood Zeek. “We’ve been struggling a bit with our extended trots,” Piferi explained. “He has little to no overtrack, and I couldn’t maintain a steady connection, which led to him coming above the bridle.”

Improving their overall connection was Lockman’s focus for developing Zeek’s extended trot. More transitions were in store, but first Lockman emphasized the importance of a good warm-up before “more difficult work: Transitions are difficult work for horses.”

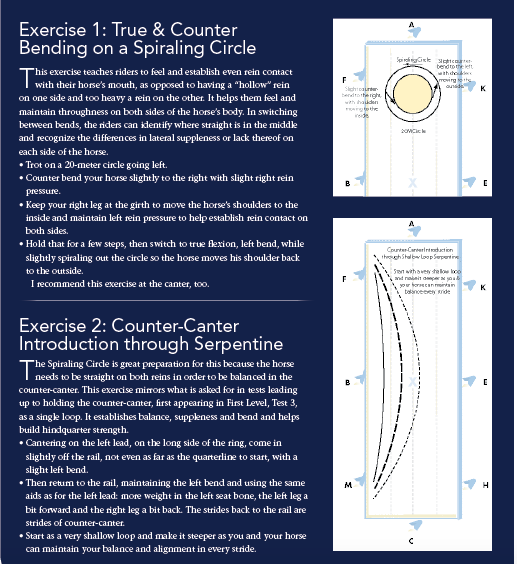

Cantering on a 20-meter circle, Lockman described the connection between inside leg and outside rein as the “inside leg pushing the rib cage out with the outside rein catching that energy.” She asked the rider to spiral down to a 10-meter circle and when that connection felt good to ask for a canter–halt transition and strive to eliminate any trot steps in between. The point was to get Zeek’s hindquarters more underneath him.

While spiraling into the smaller circle going to the left, the young rider was told to maintain the inside bend without letting Zeek’s right hindquarters fall to the outside and to keep thinking forward without letting his head come up.

Later, on the straightaway, Lockman suggested another exercise: a few strides of shoulder-in, then straighten into extended trot. This reinforced the connection and then maintained it while moving forward. “Sarah taught me to push him into the connection, making him more through and able to extend,” said Piferi after her session. “We learned a lot about getting a better connection in all three gaits and I definitely look forward to working with Sarah again someday.”

Twelve-year-old Lauren Hayatian recently earned her C-1 Pony Club rating and is a Beginner Novice eventer with the 16-year-old Quarter Horse/Morgan cross Little Dude. She appreciated tips for “getting him more up.” The first was Lockman raising Little Dude’s bit by one notch to address his habit of sticking his tongue out. The next tip was shortening Hayatian’s reins. Half halts, leg yields and emphasizing the inside-leg-to-outside-rein connection improved the energy of the horse’s gaits right away, as did a few taps of the whip on the haunches to get more engagement and activity behind.

In seeking to brighten all gaits, don’t forget the walk, Lockman said. “It’s a working gait. You should feel that he’s asking ‘When do you want me to canter?’ Keep it lively!”

Hayatian’s 15-year-old sister, Peyton, was equally pleased after her session. She is targeting First Level and wasn’t sure if her 9-year-old Appendix Quarter Horse Rosie could do the counter-canter they would need at that level. The first step was leg yields at the trot with Peyton focused on telling Rosie that her inside leg aid meant “move over, not faster.” These aids included half halts “that were more abrupt, but not harsh, by applying the same rein pressure with both hands at the same time,” explained Lockman.

Lockman also helped Peyton align her body in ways that positively influenced her horse. For example, when leg yielding to the left, she needed to “sit left, bend left and look left: Stay facing in the direction you want your horse to go.” The work paid off as Rosie’s trot slowed down while gaining swing and rhythm.

Next came counter-canter preparation of shallow loops at the canter from the rail to the quarterline, then the centerline and back to the rail. The track back to the rail is a short stretch of counter-canter. “Keeping my body straight allowed my horse to keep the lead without swapping,” said Peyton.

The sisters’ mother,

Christine Hayatian, summed up the participants’ sentiments. “We are grateful for all the hard work and dedication that Sarah put into this for kids. Pony Club always gives back. It’s awesome to see Sarah do the same.”

Sarah Lockman began as a Pony Clubber and eventer. She earned her “B” U.S. Pony Club rating and completed her first CCI** at age 15. A USDF gold, silver and bronze medalist, Lockman trains horses and riders to all levels. She is especially well known for her skills bringing along young horses, including her own 6-year-old rising star, Dehavilland. Today she runs her dressage training business in Southern California’s Orange County.