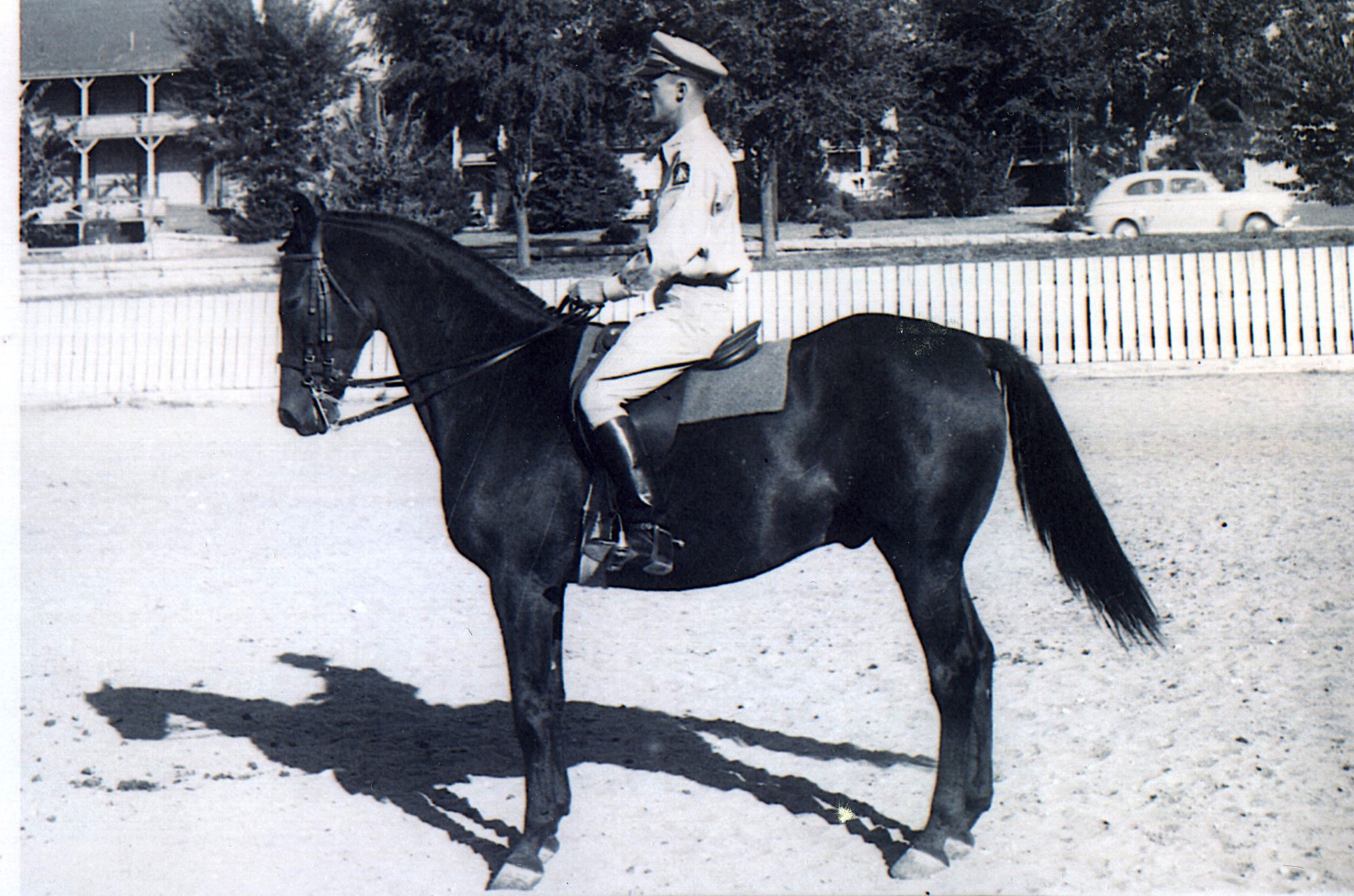

Take a glance at a photo of Alois Podhajsky when he won the bronze medal in dressage aboard Nero at the 1936 Olympic Games. You’ll notice what appears by today’s standard to be very plain tack—a flat, open saddle with unadorned flaps and a bridle without extra padding, special features or bling. The military origins of dressage come through quite clearly not only because of Podhajsky’s uniform, but also because of the emphasis on minimalistic, utilitarian equipment.

Now consider an image of Charlotte Dujardin celebrating her gold-medal victory in Rio at the 2016 Games. It is quite a different picture because of several factors, including the rider’s gender and the differences between her sport horse (Valegro, a Dutch Warmblood of sport horse breeding) and Podhajsky’s champion (Nero was a Thoroughbred ex-racehorse). Even with a superficial glance, you’ll also notice distinct differences in equipment. Dujardin’s saddle features thigh blocks (though minimal by today’s standards) and a higher pommel and cantle. Valegro’s handsome face is accentuated by a decorative bridle—white padding lines his noseband and an understated-but-elegant rhinestone inlay adorns his browband.

These changes in tack and equipment, many of which are intended to increase comfort and improve performance, are reflected at the top levels of dressage, but a walk around any local showgrounds will reveal similar changes.

Centuries of Evolution

In his book Dressage Principles Illuminated, Charles de Kunffy identifies the foundation of classical dressage as the 1773 publication of École de Cavalerie, written by François de La Guérinière and inspired by the teachings of French riding master Antoine de Pluvinel. Illustrations from École de Cavalerie show horses of that period wore simple bridles, a variety of different bits and were turned out in ornate saddle pads.

In an article written for Eurodressage.com, equestrian journalist Silke Rottermann describes the noseband on bridles favored by Guérinière: “It is a simple, thin and flat piece of leather pulled on each side through the lower parts of the cheekpieces.” She goes on to say, “[Guérinière] explained in detail how the rider can find the appropriate bit by writing about how the different bits work and fit in different mouths.” An illustration from the book shows many variations of both snaffle and curb bits were available, featuring diverse port shape and height, joints, bars and cheekpieces not completely unlike what is available today.

In Guérinière’s time, European dressage riders rode in saddles constructed on a wood frame, which featured high pommels and cantles. These saddles were similar in appearance to those still used today at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna. During the 1800s, riding needs and styles changed again with the increasing popularity of three-day eventing, fox hunting, cross-country riding and jumping. At this point, the diversification of English saddles for various sports also became more common, with dressage saddles continuing to tend toward many of the traits one would expect today: a longer, straighter flap; higher pommels and cantles; a stirrup bar that attaches farther back and longer billet straps.

According to the USDF, competitive dressage remained deeply rooted in military tradition well into the mid-1900s. It first appeared in the Olympics in 1912 and only men were allowed to compete. The USDF’s website states: “After the U.S. Cavalry was disbanded in 1948, the focus for dressage shifted from military to civilian competition and sport and began to gain momentum. Women as well as men became passionate about dressage and in 1952 the first women were allowed to compete in the Olympics.” The shift from military to civilian dominance in the sport has led to many changes for contemporary dressage, many of which are reflected in the evolution of the tack and equipment used for today’s sport.

The Contemporary

Dressage Saddle

Lisa Gorretta is co-chair of USEF’s Dressage Sport Committee, a technical delegate and FEI dressage steward and a certified saddle fitter. For many years, Gorretta owned and operated The Paddock Saddlery in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, and today runs The Paddock Group, an equestrian trade consultancy.

According to Gorretta, a change in the type and conformation of riding horse led to changes in tack. “In the early 1970s, there was the recognition that we were no longer breeding horses for the old type of conformation and this was one of the factors that signaled the change in saddlery,” she said. “Sport horses were no longer either Thoroughbreds or warmbloods that, for the most part, had a lot more cold blood than they do now. Over the last several generations, most warmblood breeding programs have introduced more Thoroughbred or some Arabian blood. So the typical modern sport horse is not built quite the same way as when horses were either one or the other: Thoroughbred or heavy warmblood. Consequently, saddles have changed to accommodate today’s performance horses.”

Laurence Pearman is past president of the British Society of Master Saddlers as well as a master saddler and qualified saddle fitter and assessor. He owns Cirencester Saddlers in the U.K., a fitting consultancy and retail shop, and also lectures frequently on saddle making and fit.

Pearman says the most significant change in design from the horse’s perspective has been the widening of the gullet, the section between the saddle panels. He explains: “This section is now generally much wider, which allows for a lot more freedom of movement for the horse’s spine and is consequently much more comfortable for the horse. Trees have also become much more open—for example, the arch at the head of the tree [the pommel] is now much wider, which allows for the horse’s scapula to move and therefore for the musculature to develop properly.”

Pearman and Gorretta believe many of the modern changes to dressage saddles can go a long way to improving the horse’s comfort at work. Pearman explains how advances in tree construction—both the materials used and the design—help to ensure freedom of movement.

Today, trees may be made in the traditional manner with wood and steel, but are also made from synthetic materials, that can be extremely durable and highly flexible at the same time. “If you take a traditional laminated-wood tree, you have a pommel and a cantle joined by rails comprised of laminates,” Pearman says. “Spring steel creates the spring in the tree and steel is also used to reinforce the arch and cantle. The stirrup bars attach to the arch and the rails. Modern molded trees made of synthetics still reflect this basic shape, but they have been molded all over to form the shape, which serves to form a very wide gullet area for the horse and to help maintain that space while the horse is working under saddle.” While this advance in tree design offers advantages to the horse overall, Pearman adds a caveat—today’s saddle with wider gullets and panels requires a more refined fit. He explains the wider gullet, so advantageous to the horse if fitted correctly, can also increase a saddle’s tendency to slip out of place.

Today, it is also common to see dressage saddles designed to be adjustable for fit by either a rider herself or a saddle fitter trained to make specific adjustments to that saddle brand with specific equipment produced by the manufacturer. By far the most common of the do-it-yourself innovations is a saddle with an adjustable gullet plate. Gorretta says, “This can be a wonderful thing, but it’s not a panacea. The fact that you can change the width of a saddle does not make it fit if it actually doesn’t fit the horse well organically to begin with.” She explains that the best use for the changeable gullet is in the case where the basic design, panel angles and clearance are correct for a specific horse who is still developing and does, in fact, change width. If that organic fit is not there, she says the changeable gullet will not “solve the puzzle” for the horse.

Trees are not the only saddle part that have undergone innovation. Pearman points out that while leather is still the most common and generally preferred exterior material used for dressage saddles, synthetic options can cut cost and enhance convenience.

Beneath the surface, there have also been significant changes to the materials used for padding. While many saddles are still made with traditional wool flocking, foam and latex are now commonplace alternatives. Gorretta points out that there is a very wide range of quality in foam panels, ranging from moderately long-lasting foams to the highest quality latex or synthetic memory foams that will endure for decades.

While the dressage saddle has changed from the horse’s perspective over the past 30 years, it has evolved just as significantly from the rider’s perspective. Gorretta says, “I started competing in 1973 or ’74. Let’s call this the ‘Pre-Let’s-Think-About-Rider-Comfort-Time.’” She explains saddles in the early ’70s were still quite open (flat) in the seat and featured extremely limited padding in the seat. In general, today’s dressage saddles feature seats that are much softer and at least a little deeper. But Gorretta identifies the most significant change to dressage saddles from the rider’s perspective: the introduction of external blocks. She explains, “Having larger external blocks makes the rider more secure. I’d like to say this only reflects in advancement in design. However, I think this also reflects a tendency in our sport toward larger, stronger, more powerfully built, better-fed horses. At the same time, the sport of dressage has moved away from its roots in the military and more toward a general population, a large population of amateur riders. Life has changed, too. People, as a general statement, are a little less fit. All of those things have had a significant impact on how saddles are made for riders—designed to provide more security and be more comfortable.”

Bridles and Bits

As saddles have evolved, so have bits and bridles. Pearman says, “It can seem like every week there’s a new bridle out on the market.” Generally speaking, it is advantageous to have so many options designed with the horse’s comfort in mind. Pearman points out some of the most significant innovations to bridle design: increased padding, especially on the crownpiece and noseband, increased width for the horse’s head and anatomically friendly cutbacks behind the horse’s ear. The goal of these changes is to eliminate pressure points on the horse’s head, hopefully encouraging the horse to move toward the bridle comfortably.

Gorretta offers the perspective that cavessons in dressage are often worn tighter than in the past, which may have led to the need for greater padding. “When I watch videos of Olympic-level competitors from 30 or 40 years ago, nothing was padded, but nothing was tight,” she says. “You typically saw drop cavessons on snaffle bridles. However, if tack is going to be adjusted the way tack is currently adjusted, I think padding intended to protect the horse’s skull and facial nerves is a very good thing.”

Gorretta believes one of the most positive innovations in dressage tack in recent years has been more advanced developments in bitting, which can directly benefit the horse. She emphasizes, “There has been much more veterinary research on bitting and the actual effects of bits. As a result, there’s more overall concern about the horse’s anatomy and the pressure and the impact we have on the horse’s facial structure in how we use bridles and bitting.”

Gorretta points out that historically bits were first and foremost objects of control. “As research has been done about how bits actually work on horses and how horses react to different metals, great innovations in designs have been made. This has improved horse welfare,” she says.

Historically most English-style bits were made in Germany or England and the primary materials were stainless steel, German silver or never-rust (a nickel/brass blend). Gorretta says that when manufacturing became more global in the 1980s, many bits were made from poor materials and the construction also suffered. She says this has come full circle and that today there are many better options for bits in design, function and the materials used to make them.

The Bling Factor

Horses are beautiful creatures and dressage is intended to both develop and display their beauty. Gorretta advises, “As long as the equipment you’re using compliments your horse and maintains the horse as the focus in the competitive arena, that’s great. Anything that detracts one’s attention so much that one is focused more on, say, the tiara on the browband than on how the horse is going overall, that’s bad.” According to Gorretta, these considerations are all part of creating an overall picture that allows the onlooker to focus on the whole horse and rider combination rather than being drawn to bling on the tack.

“There didn’t used to be bling on dressage saddles, bridles and … well, everything,” Pearman says. “And, yes, I like the bling.” He acknowledges that traditionalists do not always feel the same, but he says dressage is, after all, a glamorous sport and well-selected tack enhances the showmanship.

The Importance of Good

Horsemanship

Since the days when competing in dressage was reserved for members of the military, tack has evolved to meet the changing needs of riders and their horses. Overall, horses and riders benefit from the fact that today’s saddle and bridle makers, as well as manufacturers of bits, girths, auxiliary pads and other equipment, are generally informed by more research than ever before. However, the number of options available today can seem daunting to riders trying to select optimal tack based on their resources and their horses’ needs.

It’s not any single element or piece of equipment that is either championed or held to blame for a problem. —Lisa Gorretta

Gorretta says balancing an open mind with good horsemanship is crucial in the selection of equipment. “One of the great things for horses, particularly dressage horses, is the adoption of the concept that success in the ring is the result of input from many—an entire circle of people,” she says. “It’s about your saddle and saddle fitter, but it’s also about your training and proper nutrition, your farrier, vet and physiotherapist, if you have one. Certainly with international horses, they have that ‘village’ of people giving input and it’s not any single element or piece of equipment that is either championed or held to blame for a problem.”

The Right Equipment

by Ingrid Klimke

Adapted from Training Horses the Ingrid Klimke Way, by Ingrid Klimke. Available from

Trafalgar Square Books in May 2017. Visit www.EquineNetworkStore.com.

Suitable equipment is important to every responsible and aware rider. Naturally, saddle and bridle must fit correctly so that the horse will feel good and stay sound. This is as much a given as attentive care, good feed, a horse-centered attitude and appropriate work.

Saddle

I don’t intend to go into great detail about specific equipment but rather to speak a bit about the general topic of tack and equipment according to the Klimke tradition. In my opinion, a piece of equipment is not necessarily good just because it is modern. For example, I’m not an advocate of dressage saddles with thick knee rolls that jam the rider into position. I prefer a flatter saddle with less knee roll so that I can sit closer to the horse and follow his movement.

Girth

At my place, you will still see the old cord girths used with dressage saddles. This is for the simple reason that with these girths the saddles sit well and the pressure is distributed evenly when the girth is tightened. I don’t have to make the girth too tight and can thereby avoid pressure in the girth area. In addition, they come up higher, which is good because I really prefer to tighten the girth once I’m on the horse, especially with nervous or very sensitive horses. With these girths, I don’t have to bend so far over to tighten.

Cavesson

For normal day-to-day training, an English cavesson is my standard equipment. I like to change it up from time to time and ride in a drop noseband instead. I do so because with the drop noseband the pressure is not only on the bars of the mouth and the poll, but is also distributed over the nose, which allows me to influence the horse more effectively and lightly. Having said that, a drop noseband does not work on every horse. Some horses don’t find it comfortable.

Spurs

I ride all of my horses using short, dull spurs both for schooling work and ideally also in competition. Normally, the inside of my calf lays relaxed against the horse’s side, so the spurs don’t come into use. If my horse does not respond to my driving leg aids, then I can give one short driving aid with the short, dull spurs, which reminds the horse he should react immediately to the aid from my calf the next time. If he reacts appropriately, I praise him and I know that the next time I will only need to use the inside of my leg for the aid. Chris Bartle says: “Every horse is sensitive enough to feel a fly land on him.” This means the horse knows exactly when and where the leg aid is being given and the driving leg is being used. “So train him to respond to a whisper with your aids.”

Whips

I deliberately ride with a whip very seldom and use it very specifically because I don’t want to become dependent on using one. However, if I need the whip for a specific reason, it’s there—in which case, I use it quickly and then hold it passively again so that neither my horse nor I get used to it. In three-day eventing, competitors are not allowed to carry a whip for dressage, which is the same rule as for international dressage. We want to condition the horse to be ridden from refined aids, so from the beginning, he should become accustomed to this. It’s an important goal to give aids that are as invisible as possible.

This article first appeared in the May 2017 issue of Dressage Today magazine.