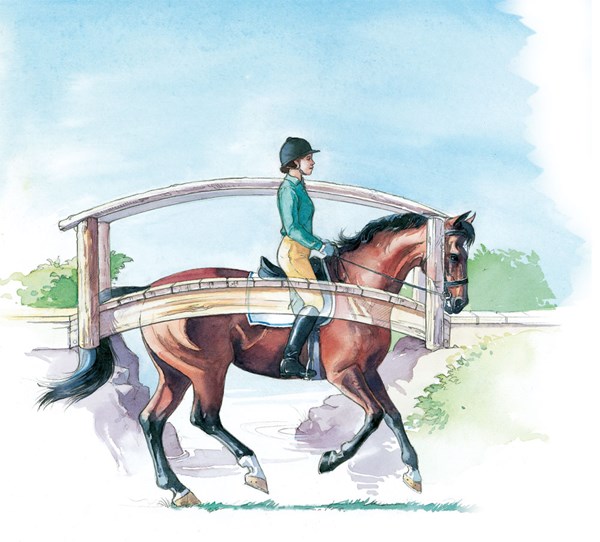

Successful dressage riders, regardless of their system, are able to develop the horse’s topline so it serves as a suspension bridge of musculature from the hindquarters through the back and the base of the neck to the horse’s poll. With the benefit of this bridge, the horse appears to lift his rider up through the withers and the saddle area, and the rider swings with the horse’s back. Some riders—including some who are competing at top levels—don’t understand this bridge, but once a rider has felt it, he never wants to live without it. It is the Holy Grail that the rider searches for in every ride. It is the ideal for which we strive.

This ideal skeletal and muscular structure of the horse channels the power of his hindquarters and allows its energy to travel without restriction through the body to the rider’s hand. When the horse has this bridge of muscle, work is much easier for both horse and rider because the bridge mechanically enables the rider to recycle his horse’s energy with half halts that engage the hindquarters to a position where self-carriage requires less effort.

Building the Bridge

In riding, there are many variables that are like pieces of a giant jigsaw puzzle. In your building-a-bridge puzzle, there are rider pieces, horse conformation pieces, horse-reaction pieces, interpretation-of-aids pieces, temperament pieces and your horse’s heart or his willingness-to-please pieces. All of these physical, mental and emotional puzzle pieces interact to create different possibilities for making work easy or complicated for the horse.

In this article, we’ll look at all of the pieces of the bridge-building puzzle. First I’ll outline the physical pieces that are necessary for building your horse’s bridge of muscle. They include:

1. Impulsion is the input of energy that travels from the horse’s hind legs and reaches (or does not reach) the rider’s hand. It is the source of power that is necessary to create and allow the bridge to form and extend to the bit. The rider needs to have impulsion or released energy in order to direct it through the body and then recycle it with half halts that create roundness. Unless the horse’s hindquarters are poorly conformed or some sort of pain is involved, impulsion depends on the reaction the rider gets from the forward-driving aids.

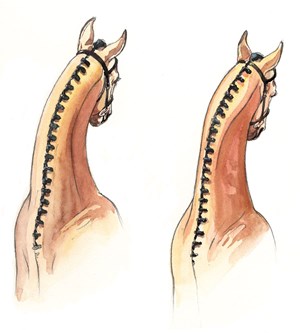

2. The energy is then channeled through the horse’s back and the first third of the neck in front of his withers—or the base of his neck. This is a common weak-link in the bridge because energy often has difficulty traveling through this part of the horse’s body. We want to see a topline that is a continuous band of muscle reaching from the shoulder all the way to the poll. This width at the base of the neck is an indication of the strength of the bridge as it reaches from the hindquarters and continues under the saddle to the neck. The muscles in front of the withers should be as wide or wider than the muscles closer toward the poll, and the muscles under the neck are soft and loose.

Oftentimes when the development of the horse is wrong, the muscles in front of the withers are narrow and they become wider halfway up. If the width at the base of the neck is not there, it’s quite difficult or impossible for a bridge to exist. However, if it is there, it doesn’t necessarily mean there is a bridge, but it’s an indication that you are set up for success. Development then of the base of the neck depends partially on the placement of the neck relative to the shoulder and its conformation and shape, which we’ll discuss in a little while.

3. The energy then continues from the base of the neck as the horse “steps through the poll.” I use the term “steps through the poll” to describe the physical attitude of the horse’s head and neck necessary for creation of the bridge. Imagine a horse as he stands in his stall and looks expectedly into his feed bucket. He shapes his neck in an arch and has an element of reach in his stance.

That’s the look of a horse that is stepping through the poll. His neck actually lifts up and becomes rounder in order for him to look into the bucket. He extends his upper muscles, and his under muscles soften naturally. He adopts the posture himself as opposed to occasions when a rider closes the angle of the poll with his hands to bring the horse on or behind the vertical. When the horse is stepping through the poll, he allows his rider to position him to the left or the right without resistance or excess neck bend or shoulder displacement. Once the rider has positioned his horse through the poll, he can soften the inside rein and the horse won’t lose his position to the inside. When the horse is truly stepping through the poll, he allows the aids to travel through the neck and the jaw to the next step, which is…

4. Stepping to the rider’s hand. The horse must step honestly toward the contact. There are a number of reasons why a horse may have difficulty stepping to the hand. He may be lacking some of the previous three requirements: impulsion, connection of muscle at the base of the neck or soft suppleness through the poll. Perhaps he has teeth problems or he may have a negative concept about contact because he has been ridden in a way that makes him afraid of the bit. If the horse has a poor shape of the neck, it also will be harder for the energy to reach the hand. The more that the horse is soft in the rider’s hand, the easier it is to come to the next step, which is…

5. Recycling the energy with half halts. When you have created the impulsion, your horse’s neck is positioned so that the muscles at the base of his neck form a connection, your horse is reaching and stepping through the poll and the energy is received without any resistance in the hand. What next? I use the term “qualify” to explain what happens when the energy reaches your hand. The rider drives forward toward a “waiting” (or recycling) outside rein that qualifies and recycles the energy in a half halt. This causes the horse to step more under himself with his hind legs (closer to the bit and more toward his center of gravity), and he becomes rounder through his body. One must have the feeling that the horse steps through the base of his neck toward the rider’s hand with each half halt. With every correct answer the horse gives the rider, the rider releases the aids as a reward. The rider determines how much collection he wants by repeating the half halts one on top of another like coats of paint. On the other hand, with fewer half halts, the rider may allow the horse to keep stepping forward past the hand so the energy can be recycled without resistance. The Germans use the word Durchlässigkeit to mean that the horse’s energy and the rider’s aids travel in a continuous circuit without resistance in any part of the body. Americans often use the term “throughness” to describe this ideal state in which the rider can influence the horse with ease. When the horse is Durchlässig, or through, the half halts can form him into a “beach-ball” shape in which he can be very flexible and elastic. His topline becomes very round and he lifts up under his belly, raises his withers and softens the under-neck muscles without resistance.

A Knowledge of Half Halts

Once the horse is round and through, his rider needs to consciously create a knowledge within his mount of transitions and half halts so he understands how to respond to them correctly. We teach young horses half halts through transitions between gaits. When they’re well developed, the horse can do a transition without changing the gait—that is, he transitions in and out of more increased collection. In the process of creating this knowledge, the horse will certainly give some incorrect responses to half halts and transitions and the bridge will break for one of two reasons:

1. Sometimes, because riders are human, they want to use their hands too strongly in the half halts or in downward transitions.

2. Perhaps one or more physical aspects of the bridge that we’ve been discussing aren’t strong enough.

3. The result is that every time the rider affects the horse in a half halt, either asking him to come into more collection or do a downward transition, the horse instantly takes himself out of self-carriage.

The weak links in the horse’s bridge of muscle show up immediately causing the bridge to break. The horse’s hind legs may stop as he shortens and lifts his neck while he drops his withers and back. He may stop stepping through the poll by either collapsing at the poll and bringing his chin toward his chest, shortening the neck and coming “behind the bit,” or he may become rigid in the poll as he drops his back and braces against his rider’s hands.

In either case, the rider needs to start over by paying attention to whichever are the weak links in his connection, strengthening them and then persisting in training the horse to half halts and downward transitions again. Successful half halts and downward transitions are the rider’s opportunity to close up the horse’s frame and improve his balance and collection. Sequentially, here’s what happens in the downward transition or half halt:

• The driving aids of your seat and leg send power through the horse’s topline to meet the hand.

• In response to the impulsion, your hand qualifies the energy with a waiting outside rein that says “Don’t go forward faster,” and then the hind legs take a millimeter more of a step than the front, which makes a rounder, more closed-up frame.

• In the moment of increased engagement, you start to feel the horse’s thoracic lift (see sidebar, “When the Bridge is Missing,” pg. 38). He lifts up underneath your hands and seat, becoming rounder in the base of his neck. Olympian Robert Dover says that the feeling reminds him of blowing up a balloon in front of you. At this point, the rider’s half halts tell his horse whether he wants more engagement within a gait or a transition to a different gait—upward or downward.

• Finally you soften your aids to allow the horse to feel a reward for his correct response and to enjoy his expressive body. He goes forward in a shorter, rounder, more pumped up and more elastic shape.

The Height of the Neck

It is often through lowering the horse’s neck during the work that the band of topline muscle is developed. To determine the ideal height of the neck, there are many pieces of the puzzle that come into play: the horse’s age, his stage of training, his conformation, the existing musculature and strength, his temperament and his current emotional state. These variables all play a role in determining the ideal height and position of the neck that will facilitate the bridge. For a horse whose conformation or previous incorrect training has created difficulty with the upper neck muscles, the lower you place the neck, the more ability you have to cause the bulge of muscle to reach the shoulder. I suggest that the rider visually monitor aspects of the horse’s bridge. Look down at the width of the topline muscle in front of the withers and use it as a concrete visual cue. The base of the neck should look very inflated, round and wide from the poll to the base of the neck, but you shouldn’t feel you are compromising other qualities of the bridge. When you lower the horse’s neck until the base of the neck is wide, does it look and feel like he is “stepping through the poll” into receiving hands? Has he kept that element of reach as if he were looking in the bucket?

When the bridge is strong and flexible, you’ll find that your horse may or may not be on or in front of the vertical and the poll may or may not be the highest point. Now we’re going to a dangerous place because when we talk about the height of the neck and the position of the poll, things get touchy and controversial. That’s because some people make the neck low without preserving the other aspects of the bridge. You can give yourself some tests that will ensure you stay on track.

As you ride, keep the following ideas in the back of your mind:

Conformation: If your horse is conformationally low in the back or if his neck comes out of the shoulder too low, you may need to position his neck unusually low in order to keep his back up and develop a strong bridge. Likewise, poor conformation between the neck and the poll such as a thick throatlatch can complicate the training since the horse will have a hard time “looking into the bucket,” unless he can work with a lower neck.

Some breeds such as Andalusians have an easier time maintaining the bridge because their backs are short and well muscled from the beginning and the neck placement is already high. Despite the neck being high, you can still see a real bridge of musculature through the base of the neck, whereas building the bridge of these horses may be easy, they may have other problems such as flexibility and elasticity issues.

Very well conformed and healthy hind legs can help you live with other conformational problems such as a difficult neck or back. Some horses may be put together totally wrong but may perform beautifully because they are well-trained to the forward-driving and half-halt aids and because they have “heart”—two very important pieces of the puzzle! Riders need to have patience in doing their homework to create the bridge musculature in the horse with conformational difficulties. The strong back isn’t going to develop as soon in his life as it will for some others, and it isn’t going to be as easy to maintain, but he may have other attributes that make him wonderful.

Age: For the first one and a half or two developmental years of being ridden, the horse’s ability to carry a rider with an elastic, lifted back may be shaky. Three and 4-year-old auction or sale horses are often presented with high necks by riders who are sitting firmly down on their backs. There are some youngsters who have extremely strong back muscles and a neck that comes out naturally high with a full base of musculature. Although they may have weaknesses in their repertoire, they can sometimes be ridden quite high without sacrificing the solid bridge of muscle, but many other 3- and 4-year-olds need to have more education and time. They don’t have the gymnasticizing and strength to carry themselves with a high neck for long. I feel the same way about the current demands of the FEI 5-year-old test. Some individuals may not be able to carry themselves throughout the required movements of the test in an appropriate frame.

The rider who has experience feeling throughness in the horse’s back is always on the lookout for when the bridge structure is there and when it’s not—especially when the rider “ups the ante.” When the rider wants a little more engagement or asks for lateral work, he may find that his horse can’t carry a bridge through the complication that was added. At this point, I use a downward transition or half halt as a tool to engage my horse and pop his topline back up. Then I can continue with the more challenging work in a better balance with more self-carriage and, therefore, with a longer neck.

Imagine you are starting to do a shoulder-fore. With the help of some transitions and half halts, you successfully superimpose the feeling of a bridge. However, when you add a bit more angle and bend to make a shoulder-in, you feel, all of a sudden, that the horse shortens, the trot becomes less swinging and the connection becomes less alive because the horse hasn’t been able to maintain the bridge with the increased engagement and angle. As a rider you need to listen and recognize the particular challenges you gave your horse that were unsuccessful and find a way to help him maintain the bridge under the demanding situation. As a trainer, you are offering him challenging little tests. Recognize the point where the bottom will fall out and either don’t go to that point or find the aids that will help the horse succeed through it. The bottom line is that the rider must only work within the range that he is able to maintain the bridge.

Temperament and current emotional state: On a daily basis at home, you may feel your horse always has a solid bridge underneath you, and you can ride him with a relatively high neck and have a good feeling in your seat and hand. Then you experience the common disappointment of taking him to a horse show where he is stressed. Since he is tense, he becomes tight and inelastic in his back. Suddenly you have a harder time creating a bridge.

The place where you thought you could go with safe results is now redefined. If you’re a smart rider, rather than forcing the situation and getting into connection and throughness problems, you will ride the neck slightly lower until you feel things are better. That may take a year or 10 minutes.

You have all of these variables when riding your horse: how warmed up your horse is, how much the engine is running, how he’s built, how much training he has, how much muscling he has, how soon he will make peace with his new environment and so on.

These variables will always be present, but constant attention to the details of building the suspension bridge will reap extraordinary rewards for you and your horse.

Visual of the Ideal Half Halt

The result of an ideal half halt or a perfect transition is the horse rebundling—or lifting up the shoulders and the back—becoming rounder and stepping toward the rider’s hands in more of a beach-ball shape with increased engagement of the hind legs.

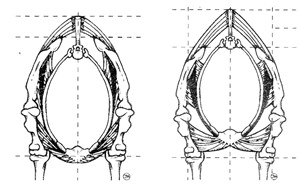

When the Bridge is Missing

If the horse’s back is tight and dropped instead of swinging and lifted (left illustration), the bridge is missing.

Then the horse and rider are dealing with two parts, the forehand and the hindquarters, each working separately. Not only is the feeling in the rider’s seat inelastic, but it also feels as if the energy of the horse’s hindquarters has great difficulty reaching the hand. It feels as if the hand brake is on generating heat and friction, so in order for the rider to get the energy to reach his hand, he needs to do more driving and emotional cheerleading. There’s a mechanical reason why the energy can’t reach the front: since the horse’s back is down, the rider is sitting in kind of a hammock, and the energy created by the horse’s hind legs is blocked. The horse’s shocks are bottomed out, and he has no ability to absorb motion because he isn’t suspended by his upper back and abdominal muscles. When the rider is able to encourage his horse to come into a position of thoracic lift (right illustration) he can show more elasticity and “boing” within his movement. As a result, the horse will tend to stay sounder and be much more expressive, and his rider will have a more comfortable ride.

When you examine a fully developed dressage horse at rest whose topline bridge musculature is missing, you have to question how the horse has been ridden or question his conformation. You must be suspicious that the correct use of the back might be difficult for him for one reason or another. There are many possibilities: The rider might drive the back down with his seat or his training techniques might not involve complete use of the back. The horse’s conformation may make it difficult for him to use his back or perhaps the horse doesn’t have the capacity to carry himself correctly because he’s been doing difficult work before he is developmentally ready for it. However, when the rider creates this bridge structure, his horse’s back develops with upper muscles that are round and lower muscles that are lifted and soft.

Truth Tests

When you place your horse’s neck low, here are some tests to give yourself to be sure that your training is correctly building a bridge.

You should easily be able to take your horse’s neck up and make his poll the highest point. That doesn’t mean that you won’t feel an erosion of your horse’s ability to maintain the bridge. If your horse isn’t quite ready to carry himself in that position, he may have a hard time maintaining the bridge. But you should be able to do it with him still connected to the bit, reaching and looking in the bucket. If you can’t do that without major losses of rhythm, suppleness or contact, then you need to confirm that your horse is stepping with an engaged hind leg through the poll and to the hand correctly.

If you’re placing the neck low and the poll becomes lower than other parts of the neck, check to be sure that you feel your horse is still looking in the bucket. There should be a universal curve from poll to shoulder—not a sharper curve near the poll that makes you feel he is disappearing behind the vertical in front of you. If you were to raise his neck up with the same curvature, your horse should be in front of the vertical and the poll should be the highest point. When you give the inside rein for a few strides, the inside bend and the connection to the outside rein should stay the same. When you give both reins, the horse should stretch forward and down, maintaining the same balance. He should not fall on the forehand, rush, slow down or hollow.

This article was first published in the October 2003 issue of Dressage Today.

A USA Equestrian “R” judge since 1979, Sue Blinks was a member of the U.S. silver-medal team at the 2002 World Equestrian Games, riding the Hanoverian gelding Flim Flam. The two were also part of the bronze-medal team at the 2000 Olympics. Blinks was named the 2000 U.S. Olympic Committee’s Female Equestrian Athlete of the Year. In 1998, she and Flim Flam were on the U.S. team that placed fourth at WEG.

Illustrations are reprinted with permission from the book Release the Potential! A Practical Guide to Myofascial Release for Horse & Rider by Doris Kay Halstead and Carrie Cameron and published by Half Halt Press.