Let’s be honest: Spend enough time ringside at large dressage shows and you’ll probably hear it: “What does she think she’s doing competing at that level? Leave it to the pros.” “What a waste—if her horse was with a professional, he’d go a lot further.” “She rides pretty well for an amateur.”

Adult Amateur competitors may be considered the backbone of dressage in this country, but that designation on a USEF membership card is much more than two simple words. For some, it’s a badge of honor: riders who juggle their love of horses with families and careers, taking lessons long after dark and working to make ends meet and afford another horse show.

But does being classified as an Adult Amateur also come with preconceived notions about a rider’s ability to succeed, whether accurate or not? While the Olympic Games used to be restricted to “amateur” athletes, today it is more of an exception than the rule to see Adult Amateur competitors at the highest levels of international sport. But two Grand Prix competitors, Alice Tarjan of Oldwick, New Jersey, and Charlotte Jorst of Reno, Nevada, agree that while these lower expectations are sometimes experienced or overheard, they have made the decision to pursue success in open divisions anyway.

The Amateur Advantage

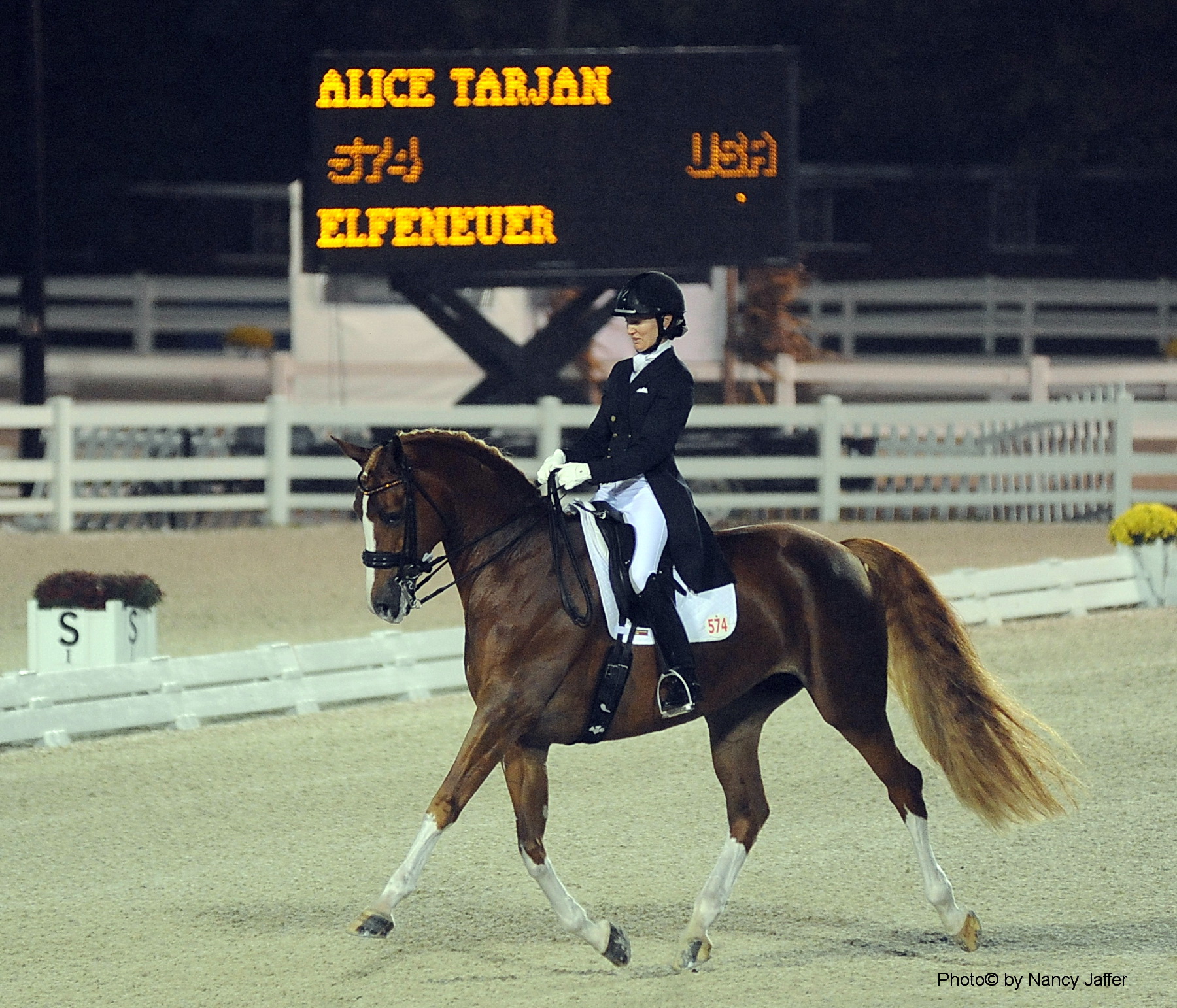

Adult Amateur Tarjan, 38, grew up in Pony Club and competed in eventing through her college years. But after law school, she chose to focus on dressage, and now as an attorney she works with her husband in industrial real estate. In the saddle she’s found tremendous success, including several victories at the U.S. Dressage Finals in the Adult Amateur ranks, wins against open riders at the Markel/USEF National Young Horse Dressage Championships and competing with professionals at the CDI Grand Prix level at Dressage at Devon and at the Global Dressage Festival in Wellington, Florida, with her longtime partner Elfenfeuer. Currently, Tarjan is developing several new young horses with international aspirations in mind.

(Photo by Nancy Jaffer)

“When I was young, like so many other horse-crazy kids, I thought I wanted to grow up to train horses full-time. But my parents told me I had to get an education and a real job. The irony is that I did exactly that, but still ride almost full-time. But I only ride my own horses and I like it that way,” Tarjan explained. “As an adult, I guess for me it never really mattered if I was an amateur or a professional. Because I still have the option and flexibility to ride in either open or amateur divisions, the way I look at it, it’s actually an advantage for me. In certain competitions like the U.S. Dressage Finals, I do ride in the amateur divisions, and I may consider participating in the CDI Amateur divisions in the future. But I also do a lot of the Young Horse classes and they’re all open, and I never shy away from that.”

By maintaining amateur status and training only her own horses, Tarjan believes she gains another advantage in the long-term development of her charges. “I buy what I want and don’t have to argue with someone about potential. I make my own decisions and get to do things my own way,” she said. “When the horses are ready to show, I show, or, if not, I keep them home and continue training—I don’t have to deal with anyone’s expectations for the horse to produce results. In some ways I feel like this is a personal advantage over some of my professional friends.

“For example, I don’t have to explain anything to anyone if I decide to pull my horse out of the show ring for an entire year to focus on training for the Grand Prix,” Tarjan continued. “One year I went all the way to Chicago for the Young Horse Championships and I didn’t present the horse well. I learned my lesson, but I didn’t have to explain to anyone how I spent a lot of money to go halfway across the country and do a lousy job. I have the luxury, per se, to just own up to my own performance and learn from it to make both myself and my horse better. To be blunt, it makes my life a little easier because I’m not depending on those paychecks—I admire how my professional friends manage those expectations.”

Don’t Stop Believing

“Amateurs are so intimidated by professionals or by the notion of being a pro,” said Jorst, 54. “And I think that’s a shame. I was determined not to let that stop me from achieving my goals.”

Jorst could be considered a poster child for Adult Amateur success: In 2013, she and her Westfalen stallion Kastel’s Vitalis represented the U.S. at the FEI World Breeding Championships for Dressage Young Horses in Verden, Germany. In 2015, she and Kastel’s Nintendo traveled to Europe to represent the U.S. at the CDIO5* Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and Hagen (Germany), coming home with a team bronze and individual third place, as well as finishing as one of the top eight Grand Prix combinations in the country at that year’s U.S. Dressage Festival of Champions. In addition to pursuing a spot on the 2016 Rio Olympic Team, she took the ride of a lifetime when chosen as one of the two U.S. representatives at the Reem Acra FEI World Cup™ Dressage Final in Gothenburg, Sweden, that same year.

“Two years ago, I did change my official status with USEF to ‘professional’ because I wanted to teach a clinic, and honestly for me at this point in my riding career it’s neither here nor there,” Jorst admitted. “But I have kept it that way because I do think it looks a little better at the top level when you’re declared a ‘pro’, even though I haven’t done any other activities since that clinic that keep me as a professional. I don’t regret changing my status because it really doesn’t affect what I do, and what’s on paper hasn’t affected my lifestyle. I don’t usually teach people and I don’t really want to, it’s just not my thing. So I may go back to competing as an amateur when I get a little older and am not competing at the international level.”

Jorst noted that she has experienced some perception problems firsthand because she is widely known as being—until recently—an Adult Amateur. “I still hear comments when I ride, even from an FEI judge, to the effect of, ‘Oh, I wish I had a schoolmaster like [Kastel’s Akeem Foldager].’ They assume that because I was an amateur, the only horses I can ride are steady schoolmasters who just carry me around the ring,” she explained. “Which is hilarious because he’s not an easy horse at all! So I get quite a laugh out of that. No one would ever say that about some of the other team riders! But that’s the kind of assumption that gets made. You’re always fighting those types of perceptions.”

No Excuses

Jorst believes that, unfortunately in some cases, negative perceptions can extend beyond simply being an Adult Amateur. “I do think there’s an element of a lack of objectivity, not just as a question of amateur or professional status,” she explained. “Because I’m a successful businesswoman, people may say that I’m trying to buy my way onto a team, whether or not I’m officially an amateur. As an outsider who came into the sport later in life like I did, that kind of negativity can be really intimidating.”

“Even though I haven’t personally experienced a time where I felt like I wasn’t being taken as seriously because I’m an amateur, I can see where that could happen,” Tarjan concurred. “I don’t feel like there are necessarily lower expectations for amateurs, but I do think the reality is that the amateur divisions, in general, are less competitive than open divisions, but that’s the whole point: to give amateurs a place to compete against their peers. That’s fine and there isn’t anything wrong with that. Amateurs have real lives and careers outside horses and usually can’t devote the same degree of time and resources to riding that a professional can.

“The way I approach it is, that at the end of the day, if you want to play the game and do well, there can’t be excuses,” Tarjan continued. “Regardless of what you are, professional or amateur, if you ride in a big show or CDI, it’s the judges’ playground there and if you don’t score well, you need to learn something from it and go back and work to get better. I believe the judges will score what they see, and it’s your job to make it happen and ride a good test, not complain about how your status supposedly affects your score.”

Do these amateurs believe that public perceptions of their success would be different if they had declared as professionals or gone pro earlier in their riding careers? “I think it’s a personal decision, and when it’s time to make a change, you just do it. I was always very forthcoming about being an Adult Amateur—I never tried to hide it just to further my riding career,” Jorst explained. “So I always encourage others to go for it as well because I believe fear holds people back. Some amateurs can’t even fathom riding in the big ring with the pros, but if I do it, anyone can! I think people should be true to who they are, dare to dream big and go for it. All too often I see people who are being held back by the perceptions of others or even of their own expectations of themselves. There’s no reason for it, so stop making excuses—there’s no time like the present. I think intimidation is a very hard thing to overcome, but success should never come down to a label.”

Reaching Maximum Potential

Peruse any horse-sales website and one can find plenty of mounts deemed “amateur friendly” (or Steady Eddies) or “suitable for an ambitious professional” (often incredible movement but hot). Why does such a distinction even exist and does this mean that Adult Amateurs are at a disadvantage in finding mounts with the talent to achieve their competitive dreams? Do sellers make assumptions that a horse won’t be able to reach his potential with an amateur rider, limiting availability of top mounts for nonprofessionals?

“That’s a great question,” said Jorst. “I haven’t personally encountered a situation where I felt like anyone was outright prejudiced against me. But I do see where that can happen and have sensed a little bit in the past when I was getting started. Now that I’ve done well, I think it’s a different story. But I have to say I could see where some people might have that kind of experience.”

“I’ve never run into that either,” added Tarjan. “But I don’t buy trained horses and I think that could be a different situation. I look for talented young horses, less than 3 years old. I personally have not come across a situation where a seller felt like the horse wouldn’t reach his potential with me just because I’m an amateur. So when I’ve looked at horses it’s always been that if I’m willing to write the check, they’re more than happy to sell him to me!

“I sometimes shop in Europe, where I feel like the sellers aren’t as emotionally involved. But I also look in the U.S., where I think it’s a little different mindset buying from breeders here because they want to see the horse do really well,” Tarjan continued. “I have heard of some breeders out there who have talented horses but who may feel that if they’re sold to amateurs, they may do well at the lower levels but don’t really go to the level the horse could potentially do. But I also have done relatively well in the show ring, so more people know me and know that if I’m able, I will do something with the horse and he won’t just sit in my backyard.”

Don’t Listen to The Naysayers

Both Jorst and Tarjan noted their discouragement with an unseen obstacle that they believe can be a notable factor that impedes some Adult Amateurs’ success in dressage competition: the power of naysayers. “[Lack of support] really is annoying, I have to say, and it can get you down,” said Jorst. “Try as you may, it can be almost impossible to ignore. Sometimes my family says to me, ‘why do you do this?’ People always think that someone else has it easier. But you can never know someone else’s story or make assumptions. This is an incredibly difficult sport for everyone. That’s why I share as many of my failures on Facebook as I do successes, because I feel like it’s important for people to see that this is real life. Once in a while it does get to me, but when it comes down to it, I do this for me. And when you have a good ride and the judges reward you for it, that’s a great feeling and makes me feel better about sticking with it.”

Jorst also believes that some riders, especially amateurs, don’t pursue opportunities because they assume something is simply out of their reach or are afraid of criticism from outside the ring. But Jorst says, who cares? “If you don’t set goals and at least try, you definitely won’t get there. If you don’t ask, the answer will always be ‘no,’” she explained. “I also think some trainers are guilty of not pushing their Adult Amateur students enough. Hold yourself to a higher standard, regardless of the horse you’re riding. I may have been very naïve when I started in dressage, but I just went for it, and plenty of people were like ‘What is she doing?’ And sure, it wasn’t great at first, but it got better through persistence.”

“When I was eventing, it was a very different atmosphere—everyone was always so supportive of each other, more of a community,” Tarjan agreed. “I think a problem with dressage is that it’s an incredibly difficult but lonely sport. People can be so nasty, and you always know the railbirds are watching and judging. It’s kind of unfortunate, but true. I can imagine that there are people who say that because I’ve done very well as an amateur, I should just compete in the open divisions and ‘let someone else win.’ I haven’t actually heard it about me, but I’ve heard it going around about others, so I’m sure I’m not exempt from the criticism.

“But at the end of the day, there’s no perfect way to define the division anyway. No matter how you divide amateurs and professionals, someone isn’t going to be happy,” Tarjan continued. “Just because an amateur may be able to afford a more expensive horse, do we now create another division to separate those people from riders of more modest means? It could get ridiculous. And just because someone is a pro doesn’t automatically mean they’re very good—there are plenty of open-division riders who are much, much better than others as well as ‘professionals’ who never compete above Second Level.”

Ultimately, Tarjan believes that the point of dressage should be about a rider’s personal choices and goals, not competitive results, no matter what division she rides in. “I look at it in that I’m on my own journey,” she said. “I know where I’m at; I know where I want to go; I’m working every day both at home and in the show ring to get there; and know that I’m doing the best I can do. Everything is relative, and the division on your membership card is not a guarantee of success—or failure.”