Bought by Carl Hester as a foal, Nip Tuck (Don Ruto X Irean by Animo) is an 18-plus hand, dark bay gelding. He’s known as a hot, challenging, nervous horse who took a long time to come into his own. Even as a seasoned Grand Prix horse, he sometimes gives an impression of precisely channeled defiance—a robust, exciting artistry. Hester and Nip Tuck have competed internationally for Great Britain since 2012 with notable placings including a team silver medal and seventh place individually at the 2016 Rio Olympics, a bronze medal at the 2017 FEI World Cup Final and individual fourth place at the 2017 European Championships.

)

For this series, we based our selection of horses on the August 2017 FEI rankings. Nip Tuck was ranked fifth in the world. To provide an expert read on his pedigree, we contacted Celia Clarke. She has been breeding warmbloods in the U.K. since 1978, was the Stallion Grading Secretary of the British Warmblood Society from 1984 to 1991 and co-authored The International Warmblood Horse: A Worldwide Guide to Breeding and Bloodlines. We were thrilled Clarke agreed to comment on Nip Tuck’s breeding, but even more so because she insisted that we must also write about the bloodlines of Nip Tuck’s legendary stablemate Valegro. Recently retired, Valegro (Negro X Maifleur by Gershwin) no longer appeared among the FEI’s top 11 in 2017. But, Clarke points out: “In discussing warmblood breeding, Valegro is particularly important not only because he headed the FEI lists from 2012 to 2016, but also because he made his sire, Negro, so much in demand that the current price usual for a Negro foal at weaning is between $35,000 and $45,000!”

Both Nip Tuck and Valegro are Dutch Warmbloods (KWPN), so Clarke starts her analysis here: “The KWPN breeding program has developed only seriously since the 1960s. In Germany, we see a much longer tradition of breeding heavier horses for military purposes and more elegant horses for travel under saddle, but one way or the other, the horses were bred for great rideability. And I mean ‘rideability’ in the most literal sense—not only were these horses willing and obedient, they were purpose-bred to carry a rider as opposed to pulling a cart. In contrast, prior to World War II, Dutch breeders were much more interested in driving horses. These horses had good knee action at the trot, but not much extension.”

To meet market demands, the Dutch wanted to produce better riding horses. At first, they imported mostly Thoroughbreds to breed to their native mares (heavier horses known as Gelders or Groningens). When the results of that cross proved difficult to predict, Dutch breeders next turned their attention to imported Holsteiner and Selle Français stallions, successfully integrating dominant show-jumping lines. Eventually, to also produce top dressage performance horses, Hanoverian and Trakehner stallions were introduced to the mix, a development that mostly occurred over the last 30 years as shipped semen became a more viable option.

)

Therefore, Clarke is not surprised that Valegro is only about 20 percent Dutch blood and descends 80 percent from good quality imported horses. His sire, Negro, sired 1,300 foals, including 22 graded sons and 12 international Grand Prix horses. Valegro has three full siblings by Negro out of Maifleur, and it is also popular for Dutch breeders to cross Negro lines with other Gershwin daughters. Negro himself competed at Grand Prix and is known for producing offspring with great rideability, work ethic and an active hind leg—hence the talent for collected work, piaffe and passage. Negro’s sire, Ferro, competed at the 2000 Olympics and sired an astonishing 51 international Grand Prix horses. Ferro is also known for producing horses with great hind-leg action and potential for upper-level work.

According to Clarke, “Looking back one more generation, we see Ulft, who was more than 40 percent Thoroughbred and by the elegant Selle Français stallion Le Mexico, who was one of the world’s best sources of jumping blood. You wouldn’t look at these lines and imagine Ulft would produce great dressage horses, but he did, and nine of his offspring competed through international Grand Prix dressage. From these lines, we get horses who are flexible in the knee and have strong hindquarters, which not only allow them to snap over a fence but also to collect.” Note that we see several Thoroughbreds on both sides of Valegro’s pedigree (Pericles, Afrikaner, Ladykiller) and Valegro is 21 percent Thoroughbred.

Maifleur is the outcome of typical patterns in Dutch breeding—her dam Weidyfleur was a KWPN mare crossed with an imported stallion (Heidelberg, a Holsteiner) as was her dam, Petit Fleur, before her (Frappant, a Selle Français). Clarke points out that Maifleur’s KWPN sire, Gershwin, was the son of the Hanoverian Voltaire, a superb sire of eventers and one of the world’s most popular stallions (3,000 offspring). The Furioso line from which he descends is generally known for producing incredible jumpers. Gershwin’s dam, Aphrodite, descends from Farn via Nimmerdor. Farn, a more old-fashioned (heavy) type of Holsteiner, was known as a foundation sire of the Dutch Warmblood sport horse, mostly known for producing show jumpers. Nimmerdor, also a jumper, was his most famous son. Note that while Valegro’s pedigree does not feature a lot of close breeding, Farn appears on both the sire and dam side. Valegro is a compact, powerful gelding with extraordinary talent for piaffe and passage, according to Clarke. Despite the jumping influence in his pedigree, it’s hard to imagine Valegro rounding a show-jumping course.

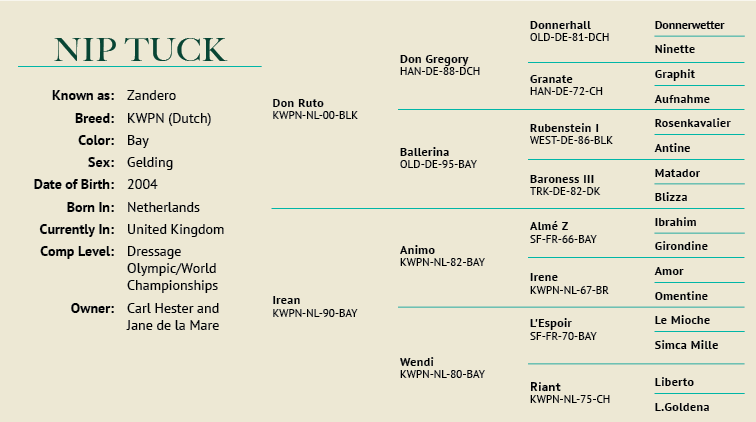

When we turn to Nip Tuck, we see a different type of horse. Leggy, long-bodied, lots of knee action—it’s not as difficult to picture him jumping a course. Clarke quips, “Here we see a horse who is a Dutch Warmblood only in so much that he was foaled in The Netherlands!” Her analysis starts with Don Gregory, Nip Tuck’s Hanoverian grandsire on the top side of the pedigree—an international Grand Prix dressage stallion who produced 338 offspring, including 13 graded sons and nine international Grand Prix dressage horses. According to Clarke, Nip Tuck’s sire, Don Ruto, was one of his less eminent sons and there is “absolutely nothing Dutch” about him: He’s a combination of classic German lines tracing back to Donnerhall and Rubinstein I. Go back five generations and Nip Tuck’s pedigree is only 6 percent Dutch. He’s about 12 percent Thoroughbred.

Nip Tuck’s dam, Irean, is the source of what “original” Dutch blood there is in this pedigree. Her mother, Wendi, descends from Dutch mares crossed mainly with Selle Français stallions. Notably, Irean, Wendi and Riant each have only one foal recorded in the studbook. Clarke presumes that these older-type lines, known for tractable disposition, were likely chosen to offset traits of Nip Tuck’s grandsire, Animo, an Olympic-level show jumper known for producing hot offspring. Animo descends from Selle Français royalty: His grandsire, Ibrahim, is referred to as a founding sire of the Selle Français breed and one of his greatest sons, the international show jumper, Almé Z, sired Animo. Ibrahim appears twice on the dam side of Nip Tuck’s pedigree. A final stallion of note is Amor, a Holsteiner imported to The Netherlands in the 1960s, known for producing big movers and mares who produced show jumpers. Going back five generations, there is only one stallion that appears in both Nip Tuck’s and Valegro’s pedigrees and that’s Amor. Finally, remember Clarke’s note that Valegro not only has three full siblings but many similarly bred cousins? Our study in contrast continues: Of Don Gregory’s 46 progeny, there’s just one by an Animo mare—Nip Tuck.

“When we look at these two pedigrees, we may see that they have nothing in common,” says Clarke. “However, these pedigrees are both a reflection of how KWPN breeders have progressed the horses they’re producing, from carriage horses to internationally competitive dressage horses.” The story we see is how native Dutch farm and carriage horses (bred for their job as such) have been improved for sport by the importation of warmbloods destined mainly for show jumping with the recent result that the strength and disposition of the mares combined with the athleticism of the stallions has yielded some of the world’s best dressage horses.

This article first appeared in the September 2018 issue of Dressage Today.