No matter how well trained a dressage horse is or how proficient his rider, their performance as a team will never be all that it can be if the horse’s bit or noseband is inappropriate, ill-fitting or misused. “It is often said that the rider’s hands need to have a conversation with the horse’s mouth. I believe that,” says Gerhard Politz, a German master trainer/instructor and member of the International Dressage Trainers Club. To initiate the most meaningful exchange, he explains, “the rider’s hands must be steady, but not rigid, with all of the joints of the arms and hands flexible and elastic, creating a soft—yet not floppy—connection.”

As an Amazon Associate, Dressage Today may earn an affiliate commission when you buy through links on our site. Products links are selected by Dressage Today editors.

The bit and noseband facilitate this ideal connection with the horse’s mouth. “When the bit is kind and correctly positioned and the noseband not too tight, the conversation can be clear and also subtle, and above all, it becomes a dialog,” Politz says.

In contrast, “when the bit is too severe and the noseband is too tight, the horse’s mouth becomes numb. The conversation is either nonexistent or it becomes a shouting match.” It is no less a problem, he adds, “when the bit is too low and the noseband too loose. The conversation becomes garbled and confusing for the horse.” In all cases, performance suffers.

The solution? A bit and noseband that are both appropriate for the horse and used correctly by his rider.

Matters of the Mouth

As Politz explains, choosing the bit for a dressage horse depends on several factors:

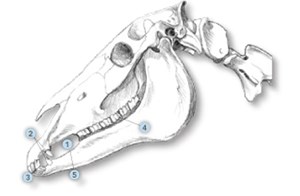

• the exterior shape and size of the horse’s mouth

• the thickness of the lips

• the thickness of the bars

• the size of the diastema (the toothless space where the bit rests)

• the thickness of the tongue

• the shape of the palate (the roof of the mouth).

As a general rule, “a thicker bit is milder than a thin one,” he explains. “However, it doesn’t make sense to put a very thick bit into a small mouth that has a tiny diastema. The placement of the bit also is of prime importance,” he continues. “It is generally accepted that there should be two creases where the bit touches the corners of the mouth. At that point, on each side, there needs to be a space of about a half-inch between the lips and the bit rings. Otherwise, the lips will get pinched, and this causes the horse to resist.

“In the beginning, most horses resent having a bit placed in their mouth,” Politz acknowledges. “After all, the bit is a foreign object in a horse’s mouth, and he will try to spit it out. He will become very fussy with his tongue and try to evade the uncomfortable pressure of the bit on it by placing his tongue in many different positions, often over the bit or even outside his mouth. Most of the time, his mouth will be open and he will try to snap at the bit rather than suck on it. As soon as any of these evasions are observed, the bit must immediately be raised, but for correctional purposes only,” Politz instructs. “When the horse accepts the bit quietly and is no longer fussy with his tongue, the bit should be placed in the normal position. Also, changing the bit from one of metal to one of rubber or a synthetic material can be helpful.”

Bit Mechanics & Choices

Given the vast array of bits on the market, Politz recognizes the dilemma that dressage riders may face in selecting just the right one for a horse. “I own two buckets full of bits of many shapes and sizes,” he says. “Some are very fancy and were bought out of curiosity. I’ve used them once or twice but never again. Some I have used occasionally when they were needed for special situations, such as for horses that needed retraining. But as the horse progresses in his re-education, I always prefer to put him in a loose-ring single- or double-jointed snaffle. Both act on the lips, the corners of the mouth, the bars and the tongue. A double-jointed bit lessens the usual pressure of the bit because the tongue acts as a buffer—much more so than it does with the single-jointed variety. A double-jointed bit is also quite unlikely, though not impossible, to press against the horse’s palate.”

The bit of choice for David de Wispelaere, an American Grand Prix dressage rider and trainer now living in Europe, “is a single-jointed, loose-ring or egg-butt snaffle,” he says. “But you have to be open to change if the need arises. I started a 4-year-old mare in a modern double-jointed bit that conforms to the mouth with a special curve. She didn’t like it and was constantly trying to spit it out. So I changed to a single-jointed, good old-fashioned snaffle, and she was quiet.” De Wispelaere, who emphasizes harmony and lightness in his daily work, prefers German silver for metal type. “It has the right combination of nickel and copper, and it doesn’t tarnish easily,” he says. “I also prefer silver buckles that are simple and functional, not huge and ornamental. I personally like simplicity.”

A bit that’s tried and true is the choice of international judge, author and rider Angelika Frömming, who has been involved with dressage for more than half a century. “I personally have used the double-jointed snaffle for many years now because I think it is more comfortable for my horse,” she says. What’s more, “if somebody has a rather hard hand, there is no pressure on the roof of the horse’s mouth.” Frömming adds that while “the double-jointed snaffle has existed for centuries, it had become rather unusual in the 1950s to 1970s, for whatever reasons. Out of the blue, it has had its renaissance.”

The Role of the Noseband

No bit—whatever its design and construction—will sustain meaningful communication between a rider’s hands and a horse’s mouth if the noseband that the horse is wearing is unsuitable or improperly adjusted.

The reason? Simply put: It makes self-carriage impossible. “A tight noseband—especially when combined with a thin [severe-acting] bit that already may have caused the mouth to become insensitive, even numb—can put pressure on the horse’s poll,” Politz explains. “When all this happens, the horse goes into protection mode and he grabs the bit as he clenches his jaws. He is unable to chew on the bit, and salivation is nearly impossible. In severe cases, the tongue becomes immobile and sometimes even discolored. It is unfortunate that the invention of the so-called crank noseband has caused many riders to do precisely that: crank the horse’s mouth shut,” he continues. “I totally reject this practice, not only because it is detrimental to the horse’s well-being and contrary to classically correct training, but because it is also a testament to poor riding skills.

“Both the U.S. Dressage Federation [USDF] and U.S. Equestrian Federation [USEF] have recognized this deplorable practice and have taken steps to prevent it,” Politz explains. “USEF Rule DR121 states that there has to be enough room for two fingers to pass between the noseband and the horse’s jaw. Naturally, this is a little arbitrary as all fingers are different. However, the intention is clear: to leave enough room for the horse to be able to comfortably chew on the bit. Chewing on the bit is not the same as chomping on it. The action involved in chewing is similar to that of sucking on a lollipop. In order for this to happen, there has to be mobility of the horse’s tongue and lower jaw. When the horse connects honestly through his whole body into the rider’s hands—provided they are steady and sensitive, and half halts are skillfully applied—the horse ‘chews himself off the bit,’ as I say, and becomes light in the contact. This is true regardless of his level of training.”

World Views

“As a judge,” says Frömming, calling on her quarter-century’s worth of experience, “it is of uppermost importance that the bridle is fitted correctly. “I have always looked to see that the noseband is not too tight or positioned too deep or that the bit does not appear too wide. The flash noseband with the crank is a problem, for sure, because one can pull the noseband very tight with that system. As long as I can remember, there have been discussions on how to correctly fit a noseband. The simple rule exists —as it does in so many places—that between the nose ridge and the noseband there has to be room for two fingers. It is described that way in our new German guidelines.

“For several years now,” she continues, “there has been a special bit check at the Bundeschampionat [German national championships] for the 5- and 6-year-old dressage horses before the ride to ensure that nosebands are not pulled too tight. They are the only classes worldwide where the bit is checked before the ride. This check was created because the judges had complained repeatedly about nosebands that were too tight. There had previously been a financial fine due to a too-tight noseband. So we have the rules and the officials. Our national federation and the judges try their best, but, regrettably, many riders don’t care and, consequently, are sometimes not punished enough for it.”

“The biggest mistake I see nowadays is nosebands that are too tight,” says de Wispelaere. “When you go to a tack shop, most bridles come with a crank noseband. It has just become the fashion.” From time to time at his clinics, the popular instructor encounters a horse whose noseband is excessively tight. “I’ll ask him why he has it that way, and he’ll respond, ‘My regular trainer tells me it has to be that way.’ If I ask why, he doesn’t know.

“Once I went to see a young horse at a sales barn, and I asked, ‘Why is the noseband so tight on a horse that has been only six times under saddle?’ I was told, ‘My trainer said it would avoid tongue problems.’ So for everybody, it’s just become normal to crank the noseband tight. Horses get mouth and tongue problems because there is too much pressure on the mouth. It’s the rider’s hands that cause problems.”

Considerations for Fit

Dr. Christian Schacht, veterinarian, FN-certified instructor and horse-management expert, likes to compare the tightness of a noseband to how a person might adjust a belt around his waist. “The belt should not constrict you while holding your pants in position,” he explains. “Imagine how uncomfortable that would be. The incorrect adjustment of a bridle and flash noseband can cause discomfort and impede the horse’s mouth and activity, resulting in problems with connection and throughness,” he continues. “We know the noseband should be positioned two fingers’ width below the facial crest [cheek bone]. It is important that the noseband not touch this area because a large facial nerve exits right under it, and it is sensitive to painful pressure.”

Politz agrees: “The flash noseband—essentially a cavesson with a lip strap—has become quite popular because it is believed that the lip strap helps control undesirable movement of the mouth and possibly will prevent problems with the tongue. But the cavesson portion must be placed approximately one to two fingers below the facial crest so it cannot rub on the bony protrusion. In this position, the lip strap is high enough to allow for sufficient flaring of the nostrils. When it is adjusted correctly, it is quite an acceptable tool. However, when the lip strap and crank noseband are tightened to the extreme, the effect is detrimental.”

For horses with large ears, Schacht explains that “the edge of the headpiece can press against the base of the ear. This pressure causes defensive reactions and problems with contact and yielding in the poll. In recent years, the horse industry has been producing specially padded headpieces with cutouts for the ears. These may not be so attractive but horses love it.”

The Experts’ Choices

With regard to his own horses, Politz says his personal preference is the old-fashioned dropped noseband, “which has sadly gone out of fashion.” He says the dropped noseband can be rather difficult to fit. “If the strap across the nose is too long, and even if the chin strap is only moderately tightened, the connecting metal rings can press on the ends of the bit,” he explains. “So you need to shorten the nosepiece. And you practically need one made for each horse’s head. It is important to position a dropped noseband high enough on the nose to allow for the flare of the horse’s nostrils,” he adds. “There is a version with buckles on either side that allows for many different adjustments.” He notes that several benefits are associated with a correctly adjusted dropped noseband: It ensures that the mobility of the lower jaw is not restricted, and it allows the horse to comfortably chew the bit.

“I ride with a French noseband, like the one you put on a hunter in the United States,” says de Wispelaere. “I will also use a dropped noseband when a horse plays with the bit too much or wants to lean on my hands. But I never make any noseband tight.”

Ill Fit & Self-Carriage

An incorrectly adjusted noseband affects far more than a horse’s mouth. It interferes with his ability to self-carry. Instructor and trainer Gerhard Politz explains what occurs: “When circumstances are ideal, the aiding system of the rider channels energy from the horse’s hind legs through his back and neck musculature toward the hands and bit. Then, through the use of skillful half halts, the rider regulates the energy back toward the hindquarters. Over time, the horse’s balance gradually changes as his haunches acquire the strength to carry more weight. When this process works correctly, the pushing powers are converted into carrying powers and, thus, the schooled horse moves in collection, resulting in self-carriage and lightness.”

Politz continues: “If, however, a tight noseband causes the horse to clench his jaws, he will grab the bit—much like a dog that doesn’t want to let go of a bone—and he will get heavy in the rider’s hand as he begins to lean on his shoulders and forehand. The energy gets blocked somewhere in the musculature, and self-carriage and lightness of the forehand become impossible. In this scenario, it’s possible for a strong-enough rider to lift the horse’s head and neck. But this forces the horse incorrectly into what’s known as absolute self-carriage (absolute elevation) instead of relative self-carriage (relative elevation).

“In absolute self-carriage, the horse gives only the impression of being uphill. In fact, he is unpleasant and heavy in the hand, his musculature is blocked and his hind legs are not swinging sufficiently under his center of gravity. There is a disconnect between the action of the front legs and the hind legs.”

Politz says that a too-loose noseband can interfere with a horse’s ability to self-carry just as much as one that is too tight. “This situation usually occurs unintentionally when a rider does not take into account that leather stretches with use. It is important to check the noseband and placement of the bit regularly and to make adjustments as needed. If this is not taken care of, the rider will have difficulty creating and maintaining a steady connection. The horse’s neck will become wobbly both laterally and longitudinally. And he will easily discover how to avoid half halts by stiffening and raising his head and hollowing behind the withers. Such unpredictability in the connection can become a major cause of tension for the horse, making throughness impossible. If the rider is frustrated with the unsteady connection and, in an effort to obtain submission, becomes busier with the hands, a vicious cycle is created.”

Bling on the Bridle

The matter of ornamentation on a dressage horse’s bridle is an ongoing topic of discussion.

“Personally, I hate bling on bridles,” says Gerhard Politz, who teaches at the Flintridge Riding Club in Los Angeles. “I prefer simplicity and elegance—anything that makes the horse comfortable.”

Retired FEI “I” judge Angelika Frömming appreciates a bit of decoration on tack and says it plays a big role in Germany, where she lives. “The riders love their horses and spend a lot of money for tack—with or without glitter,” she comments. “Even in the riding school where my own horse is stabled, the children get glitter browbands from their parents for their most favorite school horse. Why not?”

For clinician David de Wispelaere, a New York native now based near Aachen, Germany, choosing tack that enhances a horse’s natural good looks is what matters most when it comes to style. “I have several chestnuts in my barn, and I think they look nice in cognac-colored bridle leather,” he says. “I have matching saddles for my chestnuts as well. I use a plain leather browband—not too thick. There shouldn’t be too much attention to the bridle. You should see the horse’s head rather than the bridle.” He wants the width of the headpiece to fit the horse. That means “wide leather on a big head and narrower leather on a finer head.” As for bling: “To each his own,” he says. “But I think that one should appreciate the beauty of the horse without the bling.”

“My goal in riding is that I never want to look pretty on the horse, but I try to make my horses look pretty,” says Dr. Christian Schacht, veterinarian, judge and author. “If the metal on the bridle is silver or copper, I want my spurs the same. When I present my young horses, there are times I use gold glitter in a checkerboard on the butt. I use special boots and blankets for a show, and I love this.”