I’m addicted to coaching. I read books about coaching and when I watch professional sports, I’m focused on what the coaches are doing to lead their teams. Do they need to get after their players a bit and motivate them or do they need to make them believe in themselves more? I wouldn’t want to play for someone who dictated, screamed and made me feel I wasn’t good enough. Understanding the qualities of a good coach is the first step to being able to coach your horse well. The second step is knowing your horse. Those two abilities work for you as a rider to optimize your horse’s chance for success.

Skills of a Great Coach

The ideal coach:

…is a great motivator

…makes his athlete believe he can succeed

…knows the strengths and weaknesses of his athlete well

…knows how to play off the strengths and improve the weaknesses

…has a strategy for optimizing success and

…is experienced and knowledgeable about the sport and the level to be performed.

An ideal coaching style combines these skills with beauty and tact, and the riders I respect most use them when they’re riding. They don’t falsely build their horses up, and their horses never feel defeated. When a good coach addresses an issue, the horse receives the correction by thinking, Yes, I’ll try harder for you! Got it! It’s a beautiful dialog because of the coaching style. Ride your horse as if you were the ideal employer. When your horse loves going to work for you, you’ll get the best results from him.

Knowing Your Horse

When I travel to give clinics, I see some riders who have a false reality of how good their horse is. They’re caught in that love factor and they’re not working to find out how they can be better.

I also see horses being told they’re wrong, but those horses often don’t understand what was wrong. For example, if the horse was too strong, a rider might stop him promptly. That tells the horse, “stop pulling.” But that’s all it says and it doesn’t prevent the horse from pulling again 20 strides later. Great coaches want to know why the horse was pulling. Maybe he was frustrated or maybe he was tired. Perhaps he misunderstood the rider. He might be out of balance or he might need suppling.

I’m not saying that halting was the wrong correction, but what the rider does after that is what matters. The rider might decide that his horse was tired and so he takes a walk break. Maybe the horse had just been asked for three extensions. In that case, the good coach says to himself, Of course he’s pulling. I need to own this problem. Thinking like a coach is working for your horse and for success.

Once a rider knows his horse and has that coaching attitude and ability, he can plan a custom workout that optimizes his horse’s chance for success.

The Custom Workout

Developing a custom workout requires not only knowing your horse but also knowing the task at hand. Let’s say you have a Second Level horse. The test movements required at Second Level are shoulder-in, travers, renvers, collected and medium gaits, simple changes, rein-back and turns on the haunches.

We also know the ideal complete workout for a Second Level horse should include stretching, lateral work and transitions within and between gaits. It should include relaxation, high concentration, motivation, exercises that improve a weakness and exercises that build upon the horse’s highlights to improve self-esteem and refresh the horse. For me, thinking this way for each individual horse is the most addicting aspect of training horses.

If you and your horse are both familiar with the Second Level exercises and you know what a workout should include, then think outside the box to figure out how you can be the best coach for your horse. My advice, for the moment, is to forget what is normal. For example, the usual thought about stretching is to do it at the beginning of the ride. If your horse can’t stretch very well in the beginning of the ride, don’t do it. Stretching should be included at some point, but maybe your horse doesn’t do it well until the middle of the ride.

Forget what is classical and correct and forget what last week’s clinician told you. Instead, simply listen to your horse and ask yourself What does my horse thrive on?

• Some horses love to have the clarity of sets. They know, First I do this and then I do that, and the consistency makes them comfortable.

• Some horses like to change the frame a lot but others use that as a way to get out of the work.

• Some horses are good at piaffe, and it makes the gaits better balanced. Maybe your horse can use that early in the ride.

• Maybe your horse’s best gait is canter. Whereas the norm is to walk in the beginning, then stretch in the trot and then do some canter work, start with the gait in which your horse has the best balance and the most confidence. So canter before you do trot work. Try that for a week or two, and if your horse gets better and better, put it in a journal. Whenever I have an idea that proves to be successful because my horse told me so, it gets written down and then I can go back to it later.

Doing the things your horse loves makes him feel good. As you listen to your horse, you’ll find his weaknesses, too. Be careful not to attack a weakness. Instead, make it better little by little. Addressing a weakness too strongly by trying to suddenly make it a highlight can overwhelm your horse, which will most likely affect his desire to work for you and cause a lack of confidence. Maybe, for example, your horse has trouble keeping the rhythm and bend in lateral work. That issue needs to be improved gradually day by day and month by month. If you think, I have a show in two weeks and my half pass to the right is a 5, and then you try to make it an 8, you may end up with less than a 5 and kill your horse’s spirit in the process. Work on the weaknesses wisely.

• Does your horse fatigue quickly? Then take more walk breaks.

• Do your horse’s gaits feel tight? Maybe he needs to stretch more often.

• Some horses can’t concentrate for long, and that should determine the time you work on one exercise.

Developing a productive personal warm-up is an art. Read your horse: After the training session, how did he perceive his workout? Hopefully he doesn’t think, Uhhhh! I can’t wait to go back to my stall after all those boring transitions. Instead, he might think, Wow, we got the energy up a notch, but that was awesome! I understood that!

The good coach asks himself, How much can I push right now? What is fair? Should I take that break mentally or physically? Maybe you think your horse needs a few days break from the challenges and then you can ramp it up again.

The coaching rider ought to be able to inspire the horse, rev him up without tension and then relax him with beautiful, subtle, quiet aids. That’s the addictive situation we’re trying for. You’ll be rewarded with an elastic, supple and confident horse under you.

A Movement as A Sensation

Your horse experiences a movement such as shoulder-in as a physical sensation. If he resists, it’s not because he doesn’t want to do shoulder-in or he doesn’t have the work ethic or that resistance is in his mindset. When he enters a difficult movement, he gets a sensation in his body. He might feel tight in his poll, in his right shoulder, his back or his right hock. His body says, That’s difficult. It’s not his mind saying he doesn’t want to work for you. If we think about the feeling or the sensation that a particular movement gives the horse, we can learn why he might shut down and we can learn what he needs.

Let’s use shoulder-in as an example. But first, we should define shoulder-in and look at how your horse’s body parts are influenced in the movement. Instead of his body being on a straight line, it is bent (let’s say to the right) on a three-track angle to the arena wall. The shoulders are pointed as if he were going to go across the diagonal. Now the shoulders and forelegs can’t go straight because if they do, the horse will, in fact, go across the diagonal. So you tell him, “No, no, we’re going this way—directly down the long side.” Now your horse needs to open his shoulders so his front legs step to the side—to the left in this shoulder-in right. That’s a completely different physical sensation to the horse. Your horse has to welcome the sensation of the shoulders opening and stepping to the left in shoulder-in right, and as a good coach, you teach him this and encourage him through it.

The Ideal Shoulder-in

The ideal shoulder-in starts with the ideal collected trot: Imagine an elegant, cadenced trot on a straight line. The contact feels super and the horse is in a beautiful balanced frame. He’s active, energetic and swinging through his back.

If, when you enter a shoulder-in, any aspect of the ideal trot changes, then it isn’t a shoulder-in. The rider has to accept that even if the bend is perfect and the tracking of the legs is perfect, it isn’t a shoulder-in if the trot expression changes by getting flatter than the horse’s ideal trot. Even though you could get a 7.5 for it, you, as a rider and a coach, can’t be satisfied with it if your horse shows you better gaits on a straight line. You’re satisfied only when he reaches the optimum. If he has a gorgeous trot, then you want the same feeling of animation and confidence in the shoulder-in as you have on the straight line.

When the horse enters the shoulder-in from his ideal trot, many things can go wrong:

• The contact can suddenly change.

• The horse can lose rhythm.

• He can lose the bend and swing the hind legs out onto four tracks. Then, instead of engaging the hind legs in bend, he has stiffened and pivoted onto the forehand.

• The horse can lose his balance.

• He can get behind the leg.

In addition, each individual rider’s understanding of shoulder-in and the coordination of aids complicate the matter, but basically we just need to control the horse’s shoulders. To help control the shoulders, check out the sidebar, “Remember the Outside Aids,” on p. 43, and try the exercise. When your shoulder-in needs help, you need to coach your horse through his problems.

Coaching Through Problems

When problems arise, the good coach says to himself, Well, that movement isn’t so easy for my horse, so how can I gymnastically find ways to improve his confidence in that sensation?

It takes a bit of experience to break the movement down, think it through and make good choices. But I hope that most riders reading this have a trainer or a coach who can help them step back and analyze, realizing that horses don’t inherently want to be resistant. The movement often just needs to be re-explained or perhaps explained differently.

For example:

Maybe it needs to be done in a different tempo. Find the ideal tempo. Some people are inclined to slow the horse down to keep a consistent rhythm. I’m not saying that’s wrong. That might be effective for a hot horse because there’s plenty of activity in a hot horse. But for a lazy horse, there isn’t enough internal energy to lift the shoulders. If you slow the lazy horse down, he will become disengaged and on the forehand. You need enough energy in the horse so he can lift his shoulders. The foundation requirement is energy and desire, so the horse can lift his shoulders and learn to go down the line with it.

Maybe you need to ask for fewer strides. You might enter the shoulder-in well, but then maybe he loses the rhythm or gets behind the leg. Instead of doing a shoulder-in down the entire long side, ride several shoulder-ins with fewer strides in each one. Or try this exercise:

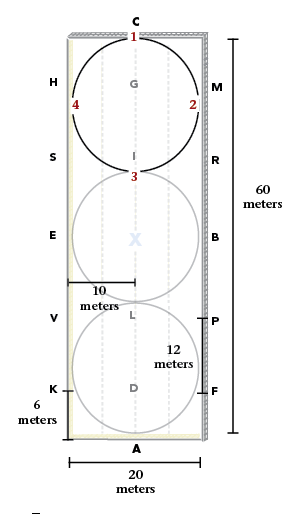

Exercise 1

1. Track right from C. Do shoulder-in from M to B

2. then turn and do another shoulder-in across the ring to E.

3. Then do another to H. Get creative so your horse learns to deliver a quality shoulder-in for fewer strides and then he can put them together.

If you have a rhythm problem, maybe you need to decrease the bend. Then the shoulders will stay more level and the horse will have an easier time keeping the rhythm.

Transitions might help. If your horse gets tight in his back, try using trot–walk–trot or canter–trot–canter transitions. This will help relax the back and create swing and elasticity in his gaits. If your horse is out of balance and/or a bit dull to your aids, try using trot–halt–trot or canter–walk–canter transitions. This will help him to rebalance and create more impulsion as well as create more sensitivity to your aids

Maybe you need to ride your shoulder-in in a different frame—either longer or shorter or higher or lower.

Maybe you need to do shoulder-in after another movement so you set it up differently. For example, try this:

Exercise 2

Ride transitions between half pass right and shoulder-in right.

1. Track right from C. At M, half pass right to the quarterline

2. On the quarterline, shoulder-in right

3. When you are between B and E, half pass right to the centerline

4. On the centerline, shoulder-in right

5. At D, straighten and turn right.

6. Repeat from K or change directions and do the exercise to the left.

This exercise helps a horse figure out how to be lighter, more balanced and freer through the inside shoulder.

Reading your horse is an art. Let him show you the way. His feedback is critical. Learn what he thrives on that builds his confidence and what he finds difficult that needs nurturing. The more a horse thrives, the more he can feel good about himself and the more he will be willing to try during hard moments. If you have that coaching mindset in training sessions, you’ll be ahead of the game. Through the horse’s mind is the best way to his body.

Remember the Outside Aids

Riders often get too addicted to the aids on the inside of the horse in shoulder-in and in other movements, too. Riders think about how the inside rein feels and if the horse is bent around the inside leg, but while they’re feeling that bend, they’re too often ignoring the opposing side. The inside is only 50 percent. The shoulder-in has no chance if the horse is soft on the inside but flat and dull on the outside. If the horse is dull on the outside rein, he is leaning on it and there is no longer a connection. The horse needs to feel as alive on the outside as he does on the inside, so riding the corner or circle correctly before any movement is critical. Without help from the outside aids in corners, circles and movements, the horse will tip to the inside, flatten and slide through the outside.

Create exercises that balance your horse left and right so he feels alive in both reins, not alive in one and dull in the other. Try this exercise to improve the influence of your outside aids.

1. Begin tracking right from C. At M, prepare to leg yield right to the quarter line. This preparation to leg yield aligns the left shoulder. It gets the poll correct and the horse supple in the left rein.

2. In the leg yield right, feel that the left side of your horse becomes stable and supportive as your horse steps from behind with his left leg as a result of your left leg aid.

3. On the quarterline, ask your horse to bend into that stabilized area and develop shoulder-in right. You should feel that the shoulders move to the inside easily and the outside of your horse is alive and working through.

The Three Phases of Learning a Movement

In my mind, horses learn a movement such as shoulder-in through a progression of three phases, and the more you understand your horse in these three phases, the better you understand him:

Phase 1—The Experiment. In Phase 1 of the horse’s learning a movement, it is an experiment—a new experience. At this point, you’re doing a little research to see how your horse responds. The horse is seeing what the shoulder-in is like, and you’re observing how your horse manages his new challenge.

Phase 2—It is Understood and Mature. The movement becomes understood and mature gradually. During this phase, you don’t want to give your horse a lot of options that would be frustrating and confusing to him. He needs to have a clear understanding of exactly what shoulder-in is.

Phase 3—You Own It. After your horse understands the movement, you can start to add options. You can ride it with a few more half halts, with a little more power, a little more tempo or a little more bend. Start to experiment with that shoulder-in so you really own it. You feel you could get 8.5 or 9 every time for that shoulder-in.

For some movements, such as ones that your horse finds very difficult, I would advise that you never try to own. For example, if your horse has trouble with the rhythm in a steep trot half pass, you want to be satisfied with a 7 that is understood and mature. Don’t mess with it. If you do, pretty soon it will get irregular again and the contact will get worse. It’s not worth trying to own it because you might not only end up with a 5, but you might frustrate your horse rather than help him. Just be happy that your horse understands it, it’s consistent, mature and you can earn a confident 7. Decide what movements you can own and go for a score of 8 or 9. Those will be your horse’s highlights. This is understanding your horse. Strategy is one of the things that makes a good coach, and this is strategy.

Scott Hassler was the USEF National Young Horse Dressage Coach from 2005–2015, chaired the USDF sport-horse committee and has served on the USEF dressage committee for more than 10 years. A sought-after clinician, he has conducted many National Dressage Symposiums for USEF, USDF and several national breed associations. Hassler Dressage is located at Riveredge in Chesapeake City, Maryland, and winters are spent at Four Winds Farm in Wellington Florida, both owned by John and Leslie Malone.