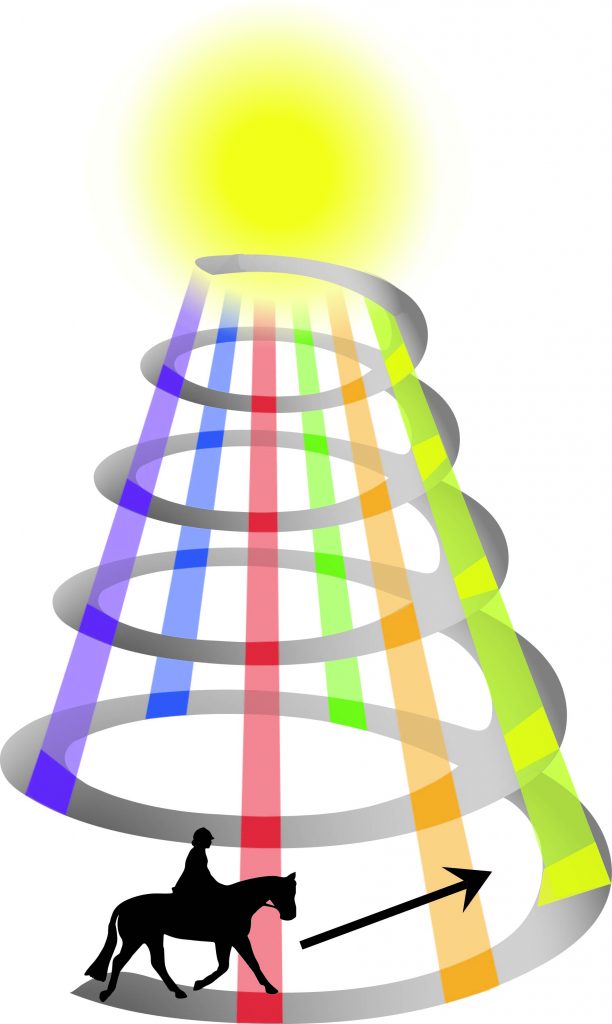

As a judge, I often write at the end of a dressage test: “Your horse didn’t have the degree of collection needed for this level.” It’s helpful not only for riders and trainers, but also for judges to understand the different degrees of dressage collection.

These recognized levels begin with first-degree collection, followed by second- and then third-degree collection. When the horse is appropriately collected for the level of his test, the work looks easy. The key to success in dressage is to make it look easy and beautiful. The goal for my colleagues at the Spanish Riding School is not to be able to do the difficult exercises. Rather, they aim for harmony between horse and rider. They want to appear as if they were born on a horse, so the movements must look easy. The goal of all riders should be harmony, which doesn’t mean you have to be a Grand Prix rider or even a competitive rider. When the riding looks easy, it’s well done. When it looks difficult, then there is strengthening and correct riding to be done. In this article, I will define the levels of collection and give a few exercises to help you on the path to its development.

Degrees of Collection

The degree of collection is determined by how much weight the horse carries with his hindquarters. As he carries more weight behind, he grows more uphill and light in self-carriage. He steps under himself and carries enough weight needed for the exercises at his level of training. This is just a matter of progressive strengthening and correct riding. You can see the degree of a horse’s collection by observing how he executes normal transitions. The purpose of transitions is not simply to move from one gait into another, but rather, to get the horse sitting more with his weight back. If you ride a trot-walk or a canter-walk transition, does your horse step under and carry himself gracefully into the walk, or does he push his neck down and plunge onto his forehand?

First-Degree Collection

The horse with a first-degree collection is usually a 4- or 5-year-old that does a working walk, trot, canter and, perhaps, some lengthenings. When he does a canter-walk transition, we are satisfied with him even though he takes one or two trot steps before walking. When he comes down the centerline in a test, he may halt with a hind foot one or two shoe-lengths too far back. If he stays steady on the bit in the halt, and then takes one or two steps of walk before picking up the trot, he will get a score of seven or eight. If this same performance is in the Prix St. Georges test, it can’t score better than a six.

Second-Degree Collection

The horse with second-degree collection does collected trot and canter. He can go from a three-beat canter to a four-beat walk with no trot steps. The horse is collected in his whole body, not just short in the neck. Whereas, we always want the poll to be the highest point with the nose in front of the vertical, at this point in the horse’s training, he isn’t always strong enough in his back to show that ideal. Corners and circles are very helpful in building the horse in bend and collection. I’ll never forget watching riders at the Spanish Riding School when I was young. They were riding very clear corners and straight lines and then corners again. A few weeks later I saw beautiful half passes and half pirouettes that looked so easy because the horse was trained to take the weight back in the corners.

Third-Degree Collection

The horse with third-degree collection carries a minimum of 55 percent of his weight on the hindquarters and a maximum of 45 percent on the forehand. He is now an uphill-going horse that grows in the withers, not just in his neck position. He is brilliant and light like a dancer. As a high level horse, he can do pirouettes, zigzags, piaffe and passage with no problem because he is strong enough in the back and hindquarters.

The old masters said you can safely put a full glass of water on a horse’s croup in piaffe because the croup should not jump up and down. In piaffe, at the highest degree of collection, the horse lowers the croup, and the hind legs lift only one hoof distance—or 10 centimeters—off the ground. In competition where the footing is too deep, the judges might not think there is enough activity, but 10 centimeters is actually considered the ideal. The horse in piaffe not only takes clear diagonal steps but he swings through his body with the correct degree of collection as evidenced by taking a minimum of 55 percent of his weight on his hindquarters.

Build Strength

Ideally, dressage builds the horse’s muscles in the same way that human bodybuilding develops strength, until the work is easy. It takes two or three months before you can see results of correct bodybuilding. For example, I have just started with my skiing exercises because I am going skiing in two months. I bend my knees when I brush my teeth or when I shave. At first, the exercises are difficult, but after the second week, it doesn’t hurt anymore. If you’re training for a marathon, you don’t push for 30 km (18.6 miles) in the beginning. Step-by-step you build condition until 30 km isn’t too difficult. An experienced marathon runner might be able to run 45 km, so then he finds 42 km (26.2 miles) easy.

It’s the same for the horse. You don’t ask your horse for a counter canter if he can’t do a correct true canter. If the horse can’t do a counter canter in less than a medium canter, you don’t ask for a simple change. If you wait until you can collect the canter a bit more, then the change will be much easier. It’s simple to make the work easy for the horse. Think like a horse and you will understand.

Horses with common collection problems—such as being wide behind or taking short steps without carrying weight behind—can be improved with strengthening. However, if you’re a horseman, you are always on the lookout for situations that might indicate a physical problem. The horse can’t talk, so you must feel for him. For example, if he always stands with his hind legs out behind him, he may have a problem in his back. Pay attention when you brush his back to see if he shows discomfort. If so, you can do the following: Check the saddle to see if your weight falls in the center of the saddle instead of too far back. Ride your warming up and cooling off sessions with a longer neck than usual. This will stretch the muscles and loosen them. Be sure the warm-up session is not too long so that he’s still fresh when he gets the real work. Do easy work for a few days. Give him a massage or call the veterinarian, but don’t be too quick to give your horse injections. Think of what you would do if it were you.

Create Self-Carriage

Self-carriage comes from the connection created by active hind legs that send energy through a swinging back into the rein contact and then back to the hind legs. Whether you have a very green horse or a very highly trained horse, you always want a soft contact that is like an elastic band.

Riders often misunderstand the term “light.” It does not mean riding with loose reins. Your horse must be connected. If you give the rein, the horse should seek it and stretch. With a proper connection, you ride the whole horse, not part of the horse. The rider with a correct connection controls the hindquarters and, therefore, controls the whole horse. The end result is a collected horse that bends his hocks, swings through his back and takes his weight back. If you know how to train the piaffe, passage and pirouette, it can only be the result of your ability to develop quality collection. The horse can’t do those movements with elegance or harmony without the strengthening of the hindquarters in correct collection.

Manage Time

Take time but don’t waste time. I remember talking with the late Herbert Rehbein about how long it takes to develop a horse. We agreed. It doesn’t depend on the wish of the rider, but rather, it is the horse that tells the rider how much and how fast he can train. Of course, the trainer needs to know how to develop the horse and how to look for the signs. Otherwise the horse might get to be 15-years-old, and his rider would say, “The horse didn’t tell me.” Horses should do the right exercises at the right age. Children usually start the first grade as 6-year-olds. If a child gets to be 9 and he’s still in the first grade, something is either wrong with the child or the teacher. He should be in the fourth grade at 9 unless there’s a reason.

When you buy a very nice horse at the auction, you hope that correct training and time will make him, not just brilliant and forward as he was at the auction, but also collected. Some horses are only for the small tour (through Prix St. Georges) because they have big movement and a limited ability to collect. You can train some horses quicker than others, but you must never forget that the horse decides the rate of progress, not the rider.

A Matter of Feel

The key to success for a rider is in the development of a good seat. The experienced rider doesn’t sit on the horse, he sits in the horse and feels the horse. He has a feeling for the speed, the rhythm and the outline. He can feel his horse’s feet, so he never has to look back to see if his horse has halted square. He also has a feeling for how much he can ask of his horse on a given day, which means he is willing to change his plans. If the canter felt lovely, and the simple changes were smooth yesterday, you may have planned to try the flying changes today. But if the canter feels awful today, you have to change the plan. Maybe you did a bit too much yesterday or, perhaps, the weather is too hot today. The horse is not a machine. I always feel that when I take one step back I can then, as a result, take two steps forward.

The horse is your partner, perhaps for as many as 20 years. He should love you not because you come to him with carrots but because you sit well and can communicate with your aids. That’s a matter of coordination with your seat, your leg, weight and rein aids. The feeling rider never creates more speed with the leg and seat than he can control in the front. Likewise, ne never uses so much hand in front that he compromises his horse’s forwardness. These skills are evidence of the rider’s feel.

The developing dressage rider has to follow his own path and not be a bad copy of someone else. He should watch many riders and look for different ways of thinking. There are many roads to Rome, and each rider has to develop his own feel and style so he can find the right road for himself.

To learn more from Arthur Kottas-Heldenberg, check out Kottas on Dressage, a book that gives important training insights. You’ll also want to check out his book Dressage Solutions: A Rider’s Guide and his DVD series.

Originally published June 18, 2010