As Forrest’s let down period ebbs into three months, I’ve been both pleased and relieved that he has settled in so nonchalantly. There was no nervous pacing in his stall, nor were there hysterics in his transition from paddock to field turn out. I don’t even think about the necessity of a stud chain and he’s a perfect gentleman to work around in all respects.

My farrier, Sean, just gave him his first trim since removing his shoes six weeks ago, and while we are heartened by his hoof growth, those heels, and subsequently, his angles, have a long way to go. However, I do feel comfortable enough to begin to teach him the concept of longeing, but am unwilling to stress his joints by doing this on a regular basis several times a week; it’s not worth it.

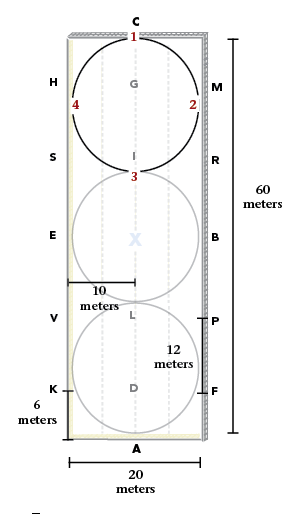

Racehorses know to gallop a straight line then hang a left, periodically. They really don’t understand being asked to go around in a 20-meter circle, and, to the left, where they have dropped that shoulder and dug in, it’s not surprising that they might do the same thing on the longe. So one can’t expect them to stay out on the end of the line from the first attempt.

Electing to make it a bit easier to understand, instead of trying to longe Forrest in my open dressage arena, I took him to his initial turn-out paddock. While more of a rectangle than a circle, I can nearly squeeze out a 20-meter space and, more importantly, it has a defined perimeter, the fence. (I choose not to use round pens, only because the horse is constantly obliged to travel a curved line which can torque the joints, overload the inside hind and cause soreness). By using a paddock, or later, an arena, I can give frequent breaks and walk straight lines with my horse.

Before we begin, we refresh what he has learned in both his stall and at the mounting block: to yield to pressure in his ribcage. I use the butt of the longe whip against his side, as well as the vocal command, “over,” as this will help me keep Forrest out at the end of the line, should he begin to fall in during these first attempts, well before the supportive addition of bridle or side reins.

It should be noted here that I am using a well-fitted leather halter instead of a longeing cavesson. I have nothing against a cavesson, mine is simply too large for Forrest’s feminine head. But it is paramount that if you use a halter, and it must fit well. The last thing you want is a halter, too large, pulling up and over your horse’s eye on the outside of his head as he goes around.

Because the paddock is familiar to him, and because he’s already been turned out a couple of hours in the field, I need not spend too much time leading Forrest around his classroom. I do, however, lead him around the perimeter, a couple of times in each direction.

And as Forrest’s left shoulder is far more developed than his right, he will be comfortable overloading it, as usual, so I begin to longe him, at the walk, staying parallel with his hip, neither line or whip trailing on the ground, clockwise, to the right. I do this because his left shoulder will be falling out to the left and in this first attempt to walk a circle, he will naturally hug the rail.

I’ve been using the vocal commands, “Waaalk,” and “Ho,” every time I lead Forrest—whether it be from stall to crossties or to the mounting block or just around the field—so that aid is already cemented in his head and he is obedient, but a bit disconcerted as he is now being asked to

“Waaalk” all by himself! I want to keep these first sessions very short, so as not to overtax him, mentally, and after a few revolutions in both directions, I say, “ho,” along with a well-deserved cookie and praise.

I’m a big believer that a horse should go exactly on the longe as you would expect them to go under saddle, so I do not allow a horse to stop and face me when I ask them to halt on the line. I want them to halt facing the way they were traveling. Likewise, I don’t let them tear around or rear or explode in a series of bucks. A couple of, “I feel good!” bucks, I’ll allow, but again, they’ve punched the clock: they’re at work and you are at the other end of the line. If allowed to continuously misbehave or be chronically crooked, a rider can’t expect a horse to be any other way once mounted.

Sending Forrest back out on the line, I will ask for no more than a couple of circles in each direction, at the trot. Again, we begin tracking to the right and with the rail to guide and give him confidence, he hears a new vocal command, “Tr-ot,” broken into two syllables so as not to sound too much like “walk,” and he obliges.

Tracking left, naturally, he was having balance issues and while I was able to carefully touch his shoulder with the whip and add, “Oo-ver” to move him, he found staying out at the end of the line difficult. In the second attempt at trot, out of frustration, he gave one, enormous, buck, which is exactly why you see me wearing my helmet—should a horse fall in and buck or rear hooves can come perilously close to ones head.

I returned him to his comfort level, walking, to the left, and praised him as he made the circuit a few times, Then I asked for the trot again and as he gave such an obedient attempt, as soon as he had completed the circle, I asked for him to stop and made a big fuss.

From this good day’s (or ten minute’s) work, we can graduate into the arena, with its better footing, a time or two a week.