“We all know that the Grand Prix horse is made in the first two years of training,” said Michael Poulin, Olympian and master teacher. The event was the New England Dressage Association’s spring symposium, where Poulin and fellow Olympian Carol Lavell, were on hand to explain that if dressage basics aren’t trained correctly there is no solid foundation for reaching the top of the training scale—the collection needed for the upper levels. Poulin and Lavell, teammates on America’s 1992 bronze-medal-winning Olympic team in Barcelona. The two have been a trainer/student pair since the early 1980s, and they presented their system to packed bleachers at Apple Knoll Farm in Millis, Massachusetts.

Lavell echoed Poulin’s sentiment about the importance of the first two years. “The 4-year-old year is a very important one,” she said. “What you do now, you’ll be dealing with for the rest of your life.” So the symposium’s format reflected this commitment to the basics.

Instead of the usual progression of Training Level through Grand Prix each day, the entire first day was spent with green horses and riders through First Level. The second day explored issues of Second through Fourth Level, and not until the third day did Poulin and Lavell present the Prix St. Georges through Grand Prix. No matter what level horse or rider they were working with, both trainers kept returning to the basics of correct rider position and connection.

Rider Position

Day One began with a rider-position longe lesson because, as Poulin stated, “The seat is the basis for training. Everything revolves around this.” Poulin shared some basic longeing exercises to promote coordination and balance.

One simple exercise helped the rider gain feel for using her core muscles to maintain a steady rein contact: Poulin instructed her to hold on to the pommel of the saddle lightly while she leaned slowly back behind the vertical then forward again, maintaining the same light contact with the pommel. The rider had to engage her core muscles and remain relaxed through her arms in order to keep the same pressure on the pommel, simulating the technique she would have to use to maintain a steady rein contact.

Both Poulin and Lavell repeated the phrase, “Too long an aid is too strong an aid,” throughout the clinic. They coached riders to use a short aid, then release it, or, “Take an aid and put it back,” said Lavell repeatedly. It was clear that the riders could give these precise aids only from a correct position, or as Poulin stated, “You can’t maintain balance in yourself or the horse if you don’t have a good seat. And balance is the key to correct training.”

The Circle and the Circle of Aids

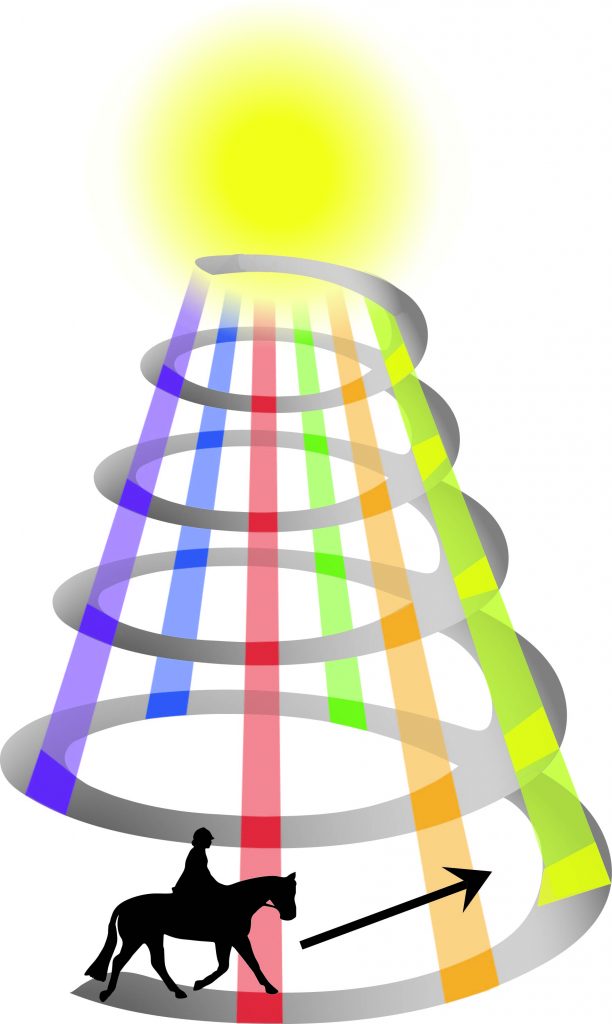

“The circle is the basis, the start, of training and of collection because it loads the inside hind,” Lavell stated on the first day. The use of the circle and the “circle of the aids” (see illustration above) was a constant mantra throughout the three days. The clinicians made clear the importance of position by showing that the rider’s body must be a conduit for the flow of energy that travels through the horse’s body, creating connection. The rider’s calves initiate the energy, then her arms, back, and hips receive the energy and act as a channel to keep the connection flowing from the horse’s hindquarters to the bridle and back again in a continuous cycle.

Poulin and Lavell stressed that the circle, because of the loading, or engaging, of the horse’s inside hind, enhances the effect of the circle of the aids. Lavell explained that correct work on a circle “puts the horse’s inside hind more under his weight, lowers the inside hip, stretches the back and promotes throughness,” thus making the horse’s body more available to the effect of the rider’s aids. The clinicians used exercises on a circle to create better balance and connection with horses from Training Level through Grand Prix.

The energetic Training Level demo horse tended to rush in the trot, and his rider asked for help slowing down the speed without shortening the horse’s neck by the overuse of the reins. Lavell put the horse and rider on a 20-meter circle and used a simple exercise of spiraling in and leg yielding out. She told the rider that it was OK if the horse fell through the outside shoulder, and not to hold on to the outside rein if he did fall out (thus shortening his neck), but rather to use her outside leg to discontinue the leg yielding for several strides.

As the horse stepped more under his body within the leg yielding, enhanced by the added loading of the inside hind on the 20-meter circle, he found better balance and slowed down on his own without the rider having to use the reins. His neck lengthened and he became looser and more relaxed. Lavell pointed out that it’s “easier to warm up one hindleg at a time,” and that she would never go straight for long if the horse is tense or strong because he has the power of both hind legs pushing straight into the bridle. The circle allowed this rider to influence the horse with her aids without him rushing away from their effect as he could have on the straight away.

At the other end of the spectrum, Poulin used a 20-meter circle to help the Grand Prix demo horse gain better balance in the tempi changes. The horse, electric by nature and extra-energized by the clinic setting, had begun to rush through the changes and shorten his neck as the rider attempted to slow him down on the diagonal. Poulin directed the rider to ask for four tempis on the circle and not to worry about the changes too much, but just to let the circle do its job of suppling the horse. “You fix the changes by fixing the suppleness,” he pointed out. With the help of the circle, the rider was gradually able to lengthen the horse’s neck and loosen his back. Then the changes began to come from a more engaged hind leg instead of the flatter, rushing changes the horse had been producing on the diagonal.

Before doing the one-tempi changes, Poulin had the same rider ride several full canter pirouettes. Again, the exercise used the principle of engagement (and thus better access to the circle of the aids) created on a circle (this time the very small circle of a pirouette) to help maintain engagement on a straight line.

Contact

Discussion and questions about contact came up repeatedly throughout the clinic, and Poulin stated that this third step on the training scale is often misunderstood. Both he and Lavell used several effective demonstrations to help teach the feel and amount of contact that are correct.

Poulin showed how detrimental too strong a contact could be by recruiting a volunteer from the audience. He placed his hand on the volunteer’s head and asked her to walk forward as he walked next to her. She walked easily forward until Poulin firmly pushed down with his hand. Her neck tightened, her chin dropped toward her chest and she could barely inch along. It was a clear illustration of what happens when the rider holds the contact too strongly and shortens the horse’s neck.

Poulin then approached a rider with his hand extended in greeting and, as the rider reached forward, Poulin moved his hand slightly to the side so that the rider was grasping at nothing. They did this attempted handshake several times. It was a simple but clear demonstration that while the contact shouldn’t be too strong, it must be consistent, otherwise the horse will be frustrated by the lack of connection and probably won’t be too eager to “shakehands” with us via the reins.

Lavell shared her favorite image for describing the ideal feel of the reins: “The weight in your arm as you’re holding the reins should be like the weight of resting your arm on a thin rope that is suspended between two poles. When that rope moves, your arm resting on it should move with it.” If the rider puts too little weight on the rope, she can’t feel when the rope is moving and can’t follow its motion. Too much weight, and the rope won’t swing at all. On that same note, Poulin demonstrated what happens if the rider holds the inside rein for too long. He had a ground person push on a horse’s inside shoulder for several minutes. When the ground person released the pressure, the horse clearly leaned to the inside, seeking the pressure that had been there. Message: If you’re holding the inside rein, you’re teaching the horse to lean in. As Lavell stated, we must “use an aid and put it right back,” that is, use an aid and go back to the neutral weight of our arms resting on the imaginary suspended rope.

Lavell used an interesting position technique to help riders gain a better feel of the contact. She had several riders shorten the reins until their elbows were almost straight so that their arms were “like the reins,” and they could completely follow the horse’s mouth. Once a rider gained a better contact, she could go back to a normal rein length, but Lavell also cautioned against letting the reins get too long, because “the longer the reins are, the stronger the rein aid is, and this gives the horse a greater chance to lean on the aid.”

Transitions

Both Poulin and Lavell instructed riders to use a lateral driving inside leg at the girth in downward transitions, especially for riders that tended to use too much rein and pull the horse into the downward transitions with a collapsed neck. Lavell explained that in the beginning of working these transitions, it was OK for the horse’s inside hind to cross over the outside hind (as long as the horse wasn’t drifting out) and that this put the inside hind more under the horse’s weight, promoting looseness in his back and helping the rider to produce the downward transition with little to no rein. The amount of stepping under of the inside hind in the downward transitions progressed from leg yielding on a circle for a green or less-balanced horse to shoulder-in to, ultimately, a whisper of shoulder-fore on the long side for the highly schooled and balanced horse. These transitions follow the same principle as the work on the circle—the added loading and lowering of the inside hind and subsequent loosening of the horse’s back increase the effect of the circle of the aids. This ultimately produces the collection of the Grand Prix horse in passage-to-piaffe transitions that begins with the trot–walk transitions of the 4-year-old.

On the final day, four horses, ranging from green to Grand Prix, were ridden in single file around the arena and did basic ring figures. They demonstrated the progression in connection and self-carriage that is created through correct dressage training. By their span in age (4 to 19), they also demonstrated the length of time it takes to bring a horse through the levels. As Poulin said, he doesn’t have a seven-day week. “I have Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday and tomorrow. Tomorrow is the day you can keep fixing all the problems.” Poulin and Lavell stressed that they didn’t invent their system; it is based on the classical principles that have been around for hundreds of years. They did demonstrate, though, that their willingness to take the time, and more time, with the basics produces consistently positive results.

Joy Congdon is a U.S. Dressage Federation (USDF) “L” Education Program graduate, a USDF Certified Instructor through Fourth Level and a bronze and silver medalist. She gives clinics throughout New England and operates Still Point Dressage in Shelburne, Vermont (joycongdondressage.com).