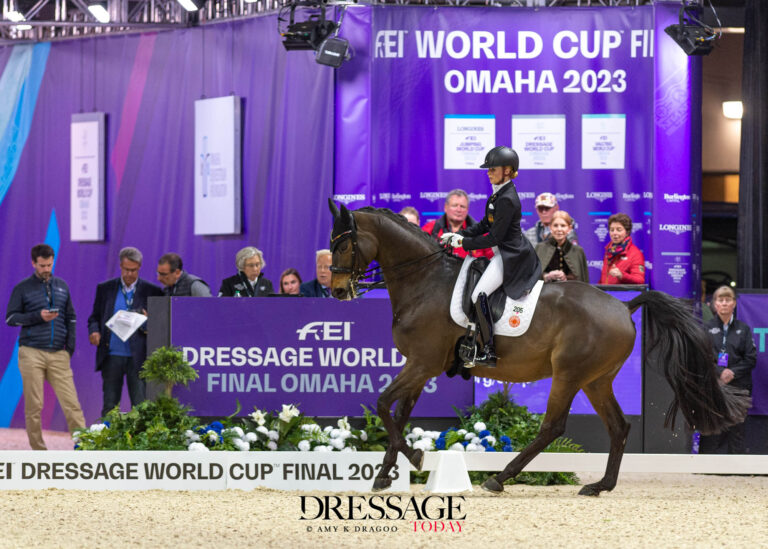

Dressage Today had the chance to sit down with U.S. rider, Michael Barisone, and talk about his philosophy on horses, training and life.

You have won 103 CDI Grand Prix on nine different horses, most of whom you have trained from A to Z. Have you met all the potential and unforeseen challenges of training young horses through the levels during your career?

Michael Barisone: No. I have not even come close. We buy a lot of young horses, so I see something new every day. I have a couple of youngsters in the barn here that I think are fantastic. But one has stuff that he throws at me that comes in a form that I have not directly dealt with before. It is all fundamentally the same, but it comes in a different order.

Having a network of people you trust and can talk to is important. No one is ever going to see everything that comes at us. You succeed when you realize what you don’t know.

At what point in your career did you have enough confidence to recognize your own qualifications to start training young horses and take them through the levels to Grand Prix?

MB: About the third horse I actually trained to Grand Prix, I said: “OK, maybe I do know what I am doing to get there.” But I actually think in the last couple of years I feel a whole lot better than I did before. About two years ago I recognized that I was not struggling anymore to make decisions. [Assistant trainer] Justin [Hardin] says to me all the time, “When you get on you always know what you want to do with a horse. You always are sure when to start and when to quit. I’m still trying to figure out what to do in this moment and that moment.” And I say, “Yes, when I was in my 30s I was in the same boat.”

You mentor a lot of 20- and 30-something-year-old riders.

MB: Yes, and I say to these young people: “Generally, the most dedicated and disciplined and focused athlete is the one who will win the most.” Being a winner doesn’t mean you get the gold medal every day. Winners go at it and keep working on getting better every day. Yes, it is nice to go to dinner at times. But the point to my day is not sitting down and having a glass of wine and looking at the mountains. I want to move mountains. Most people who don’t think like that will not understand you.

How do you define “discipline” and “focus?”

MB: Steffen Peters says: “Discipline is the bridge between dreams and achievement.” George Morris says: “discipline and details.” It is taking that 20-meter circle and working on that right bend even though you don’t want to. Even though it is the hard thing to do, you have to do it. Never get sucked out of basics. Phillip Dutton says: “The one that gets the farthest is the one that works on what he can’t do the hardest.”

Explain “the default position of retraction.”

MB: Some young horses, like teenage kids, are quite easy and others quite difficult. And some are impossible. This phase is when they get their own opinion. Usually, that’s a coming 5- to 7 1/2-year-old horse. They get stronger and they get a bit more opinionated. What they want to do is not always what you want to do. Most of them will have some type of default mechanism: stick the head up and run, grab the rein or just get behind your leg, etc. In my experience, you lick it and you move on. You carry on training them and hopefully you get to Grand Prix. Then you get through two tests, five tests or 10 tests, and now the work is getting harder and the horse is getting tired. He has not built up all that muscle memory yet of a horse that is on his fourth year of Grand Prix. And at 8 or 9, those default mechanisms generally come back.

When they go through this stage, you say you have to have energy and faith.

MB: The energy part is riding and working through it. This can take a few shows or a couple of years. The faith part is the belief that it is all going to turn out in the end. I recall that I ran into this when a certain horse was 6 or 7. I figured out how to fix it. And then I went on and had this wonderful horse. It is easy to have an unrealistic expectation. It is also easy to get convinced that, “Oh, my God, this is never going to get any better.” For example: You fall madly in love with someone. And then something goes wrong and you break up. Then you experience the feeling of “I don’t know how to get up in the morning.” At that moment you feel awful and you are sure it is never going to get better. Sooner or later, it gets better. It is the same thing with a horse. He’s going to be all right and we are going to be better at the end of it.

Your favorite motto is “Never, never quit.”

MB: You have to keep going. I have made several U.S. teams. I have also missed probably 10. If I wasn’t clocked to go, I was really close. And all these horrible things happened. Like the horse died or had colic surgery or there was one piece of paperwork that was missing that got lost in the shuffle. After the first incident in 1990, somebody gave me this book called Never, Never Quit. Every page is a story of absolutely miraculous achievements in sports. [U.S. track and field Olympian] Wilma Rudolf had polio as a child and was never going to walk and went on to win five Olympic medals. I had a terrible tragedy with two horses that are the best I have ever had in my career. One is two years out from being injured, and hopefully he is back. Never give up.

So you know when to hold and when to fold.

MB: The most challenging decision you are going to face as a rider/trainer is to know when to quit. You worked the changes heavily yesterday, but for the next three days you’re stretching, doing trot and canter and not touching those changes. You need to know when enough is enough. I find that horses are miraculous. We make mistakes as riders. If we are really good-hearted, we go home afterward and we feel awful. Caring people do that. It is amazing that you can have an awful ride, blame yourself and feel terrible about it on Tuesday. Go for a hack on Wednesday, and then Thursday you pick your horse up, and he has forgotten you ever had the bad ride.

Does rideability come first?

MB: Rideability comes with exceedingly well-trained horses. If you want your horse to sit down and lower his croup in the piaffe, he has to give it a shot. You have to be able to touch his mouth. Nothing can be off-limits if you want to be competitive. The horse must go forward and back or bend left or right when you want. The horse has to allow you into his space. You have to be able to make the horse quick or open, long or short. You have to be able to come into the corner, make sure the horse is supple, get his hind legs under and leave with a fresh horse. The horse must be well-trained so that he is easily and quickly adjustable. That is how you win.

Explain the phrase “uphill keeps things pure.”

MB: With Grand Prix heavy work—piaffe, passage and pirouette—the horse has to be able to sit. He has to rock his pelvis under, get his hind legs under and lift his withers and his forehand. If he is pulling himself with his front legs, you do not have much of a chance. Getting a horse to sit down is the key to the whole thing. How can you get a piaffe to fit the description of what it is supposed to look like if he is dragging his front legs? Also, when the whole front end is dropping, he gets strong in the hand and his neck shortens. I don’t remember a remark on a Grand Prix dressage test that said, “Neck too long” or “Horse too much off forehand.” Anybody good in the world rides with his or her horse’s hips down, withers up, neck rising and the poll at the highest point or darn near it.

What is a 10 piaffe?

MB: A 7 piaffe is 10 to 12 steps with the horse in the correct outline, sitting and relaxed. There is the possibility of 1 meter or so of ground cover. The judges are going to see the proper balance, energy and all that stuff.

For an 8, you need 12 steps that are closed up a bit more. To get a 9, you will have to do 15, where a little movement may be acceptable. But for a 10, Klaus Balkenhol used to say, “I want to see 15 steps in place, perfect in and perfect out, sitting down, and you can’t be covering ground.”

When do you put these expectations on your horse?

MB: This depends on the horse. Neruda could do 15 in place as well as any horse in the world. That was his thing. Our current Grand Prix mare consistently gets 69 to 70 percent in CDIs—she is 12 years old and going to be great. She does a presentable piaffe with a score of 7. She is honest, willing and has the right idea. But she needs a year of developing proper strength and self-carriage and getting stronger before I can really start to train on it and ask for [a piaffe] that is really good. But she also has an 8 or 9 extended trot. She has 8 or 9 changes, passage and a really beautiful extended walk. Not many get a 10 piaffe, and there are lots of other boxes in the test.

What is a 10 passage?

MB: Having ridden a lot with Johann Hinnemann and Klaus Balkenhol, every time I did a passage that was really beautiful—high and floating—either one would say: “That is not passage. It is way too open.” Passage is not, in the end, supposed to cover enormous amounts of ground. It is supposed to be really collected with enormous lift. You will make way more points when your passage is in the shape of a piaffe than you will when your piaffe is in the shape of a passage. The horse that is sitting and engaged behind, knees and hocks up and in perfect rhythm—he is doing that piaffe for a 10, and if he then starts covering ground [passage], you are going to do way better. The transitions will be way better. Everything will be better.

How does the rider’s inside leg affect the zigzag?

MB: In the zigzag, the rider will canter half pass, half pass, half pass and will slide the outer leg back to make the change and go sideways. At the moment that the horse makes the change, he goes downhill, pulls with his front legs and then drags himself through the half pass. The inside leg has to lift the horse up, forward and sideways. The new inside leg takes the whole change uphill.

How do you address the 15 tempi changes?

MB: First you must simply get your 15 ones. However, the horse can’t be tense and fly all over the place or climb into it. If he is relatively straight and the changes are clean, to get a 7 you need 15 clean and organized changes that look like the horse understands them. A 7 in every box will get 70 percent. So don’t go at it with a sledge hammer—get your test solid first. Once he understands every individual element, then start to work on where the limit is with the changes. If you try to find the unlimited flying change and you miss them all the time, then you have not accomplished anything. Better you get a 7 for straight, quality, cool-but-not-very-impressive changes than you get a 4 because you are running at them and missing.

When do you know to go for the point threshold?

MB: The first priority for a horse going into Grand Prix is to make sure he can do everything in the test competently, then address his limits. We know we will have to go for that bright pirouette gingerly because that is what he can do now. But we are going to have to open our extended trot so we can get an 8.5. And that goes for all the things in the test. It has to evolve once he comprehends it. But again, it is order of operations. First the horse has to understand it and be confident with it. Once he does those two things then we will worry about where the point threshold is. But if you try to ride for the point threshold right off the bat and he doesn’t get it, everything will unravel for both the rider and horse’s confidence. This brings it back to knowing when to quit.

Are there any other famous words that hit home?

MB: Donald Trump’s 12 inevitabilities of success: You will lose some friends,

you will think you’re going crazy, you will feel pain, you will almost talk yourself out of it hundreds of times, you will lose money, you will cry before you get it, your family and friends will discourage you, you will doubt yourself thousands of times, you will develop weird habits, people will give you grief for no reason, it will all be worth it,

then suddenly they all want to be your best friend.