Recently, I asked an extremely competent rider a question about the Training Scale. She hemmed and hawed, mumbled and apologized and said she knew that Collection was at the summit. But she didn’t know about the basics of how to get to the summit. Well, she’s not alone!

As an Amazon Associate, Dressage Today may earn an affiliate commission when you buy through links on our site. Products links are selected by Dressage Today editors.

On the very same day a Dressage Today reader named Heather Collins asked for more information for newcomers to the sport. It was not the first time we’d had such a request. A few weeks earlier, a different reader had said she was sick and tired of reading about the stars of the sport instead of more relatable riders. “Tell me how to ride,” she said. So here you go. I hope this helps.

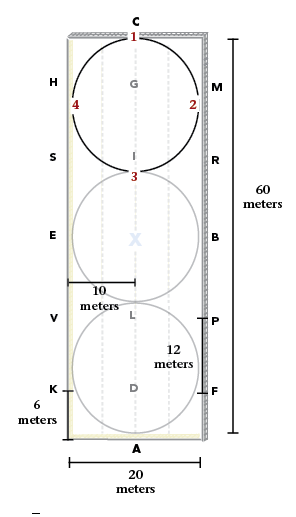

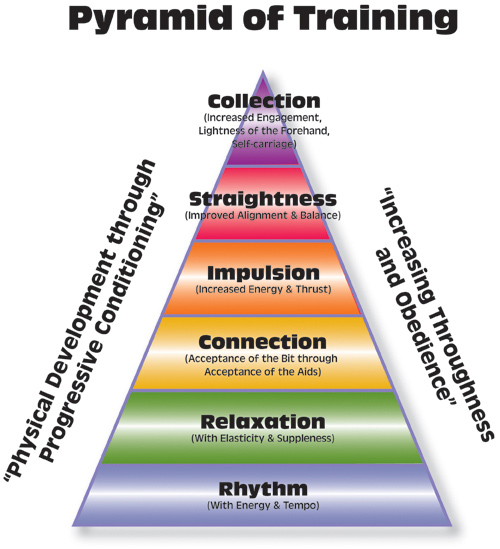

In 1986, the Training Scale was introduced to Americans through the translation from German to English of a chapter of German Olympian Harry Boldt’s book, The Dressage Horse, and it revealed—at long last—the Training Scale that the Germans had been utilizing for decades if not centuries. The Training Pyramid, as it is sometimes called, starts with Rhythm as the most basic quality and culminates with Collection. This scale of training serves as the framework for training all horses. It’s not intended to be strictly sequential, but it is generally sequential, and sticking to the basics of this recipe for success in training horses will pay off. It always does. There are variations on the theme, but the theme is always there.

The Purpose of Training and First Level Tests

Before you ride your dressage test, be sure to know the purpose. You can see that the purpose of Training Level is to confirm the first three steps of the Training Scale:

Training Level Purpose: To confirm that the horse demonstrates correct basics, is supple and moves freely forward in a clear rhythm with a steady tempo, accepting contact with the bit.

Next, you can see that the purpose of First Level is to introduce the fourth element of the Training Scale, Impulsion or Schwung.

First Level Purpose: To confirm that the horse demonstrates correct basics and, in addition to the requirements of Training Level, has developed the thrust [impulsion] to achieve improved balance and throughness and maintains a more consistent contact with the bit.

The Purposes of Second, Third and Fourth Level Tests

Check out how the purposes of our dressage tests incorporate the Training Scale:

Second Level Purpose: To confirm that the horse demonstrates correct basics and, having achieved the thrust required in First Level, now accepts more weight on the hindquarters (collection); moves with an uphill tendency, especially in the medium gaits; and is reliably on the bit. A greater degree of straightness, bending, suppleness, throughness, balance and self-carriage is required than at First Level.

Third Level Purpose: To confirm that the horse demonstrates correct basics and, having begun to develop an uphill balance at Second Level, now demonstrates increased engagement, especially in the extended gaits. Transitions between collected, medium and extended gaits should be well defined and performed with engagement. The horse should be reliably on the bit and show a greater degree of straightness, bending, suppleness, throughness, balance and self-carriage than at Second Level.

Fourth Level Purpose: To confirm that the horse demonstrates correct basics and, has developed sufficient suppleness, impulsion and throughness to perform the Fourth Level tests, which have a medium degree of difficulty. The horse remains reliably on the bit, showing a clear uphill balance and lightness as a result of improved engagement and collection. The movements are performed with greater straightness, energy and cadence than at Third Level.

Rhythm

Rhythm is the most basic quality because it’s the horse’s language in motion. That is, the rider’s aids of communication are best understood by the horse when they are given at the right moment during the rhythm of either the four-beat walk, the two-beat trot or the three-beat canter. Those who study music might best understand the beauty of rhythm and the self-perpetuating nature of rhythm that help the horse move in the most economical way. Imagine yourself at work: You might be digging a hole or whipping up a cake or pumping iron at the gym. You will be most efficient if you are doing your work in rhythm.

The terms “working trot” and “working canter” were coined as a way of helping the rider search for the rhythm and the tempo (which is the speed of the rhythm) in which the horse can work most economically. Some horses, because of lack of balance, are inclined to get quicker and quicker, while some are inclined to slow down like a windup toy winding down. If you can improve the consistency of your horse’s rhythm, you improve his balance, his comfort and the economy with which he moves. Inherent in rhythm is the flexion of one set of muscles and the relaxation of the opposite muscles, and then, of course, the one set of muscles relax and the opposite ones flex. Hence, when working in rhythm, all the muscles get a moment of relaxation within every stride. That’s why well-trained dressage horses often live long, useful lives.

The rhythm of the working trot varies from horse to horse—between about 140 beats per minute (bpm) and 160 bpm—depending on your horse’s size and his way of moving, but if your horse’s trot is, for example, 148 bpm, he must be consistent. You, as the rider, can help him maintain a consistent rhythm and tempo. The tempo of the canter is usually about 96 bpm and the tempo of the walk is often about 100 bpm. If you ride with a metronome, you can work on helping your horse retain the tempo of this rhythm. Then you learn, without the metronome, to be the metronome for your horse. You can also use cavalletti to give you and your horse the feeling for correct rhythm.

As an aside, self-perpetuating rhythm in motion not only improves the horse’s physical balance but also his mental balance and the rider’s mental balance and comfort. There’s something great about knowing what’s going to happen next, and correct rhythm is self-perpetuating.

Relaxation and Suppleness

The USDF says that the second step of the Training Scale is Relaxation. Remember the flexion and relaxation that occur when the rhythm is consistent? When that moment of relaxation is missing, you can’t go much farther in the training of your horse because development requires that muscles receive the circulation of blood and oxygen in order to strengthen. Of course, we all know that it’s hard enough sometimes to relax ourselves let alone try to help another living being (who is sometimes nervous or frightened) to relax. Within the sport of dressage, there are many basic exercises that help horses relax. Most, if not all of them, entail bending and stretching. Bending promotes lateral relaxation and stretching promotes longitudinal relaxation.

Studying a sport that has fans from different cultures has complications, but also has the enriching aspect of revealing the subtleties between different languages. So the international governing body, the FEI, calls the second step of the Training Scale Suppleness—another English word that has slightly more meaning. It can be said that you can be relaxed but not supple (such as when you’re lying on the beach), but you can’t be supple without relaxation. Suppleness implies that there is relaxation as well as some amount of energy working through the body. So the ideal jogger is relaxed and supple. The horse can’t really bend and stretch well without being relaxed and supple. But encouraging him to bend and stretch promotes both of these qualities.

Patience. When the first three elements of the Training Scale are understood and demonstrated by both horse and rider, they present a lovely picture. The ideal Training Level horse is beautiful. However, attaining this level shouldn’t take forever. Three- and 4-year-old horses are often born to go forward in a clear and steady rhythm, be supple and accept contact with the bit. So don’t set the bar too low. Clinicians often see young horses who are inconsistent, not on the bit, tense and demonstrating poor rhythm. The excuse is that the horse is young. But often the rider isn’t even making her wishes known clearly to the horse. Patience is sometimes a virtue, but not if the horse is uncomfortable and out of balance just because the rider hasn’t helped him to a better balance by explaining the first three elements of the Training Scale to him.

Contact and Connection

The word “Contact” refers to the feel between the rider’s hand and the horse’s mouth. The Connection is between the hindquarters and the forehand of the horse. You can have contact without connection but you cannot have connection without contact.

How does the contact develop the connection? When the horse goes forward in a clear and steady rhythm and he’s also relaxed and supple, the energy goes from a thrusting hind leg through the relaxed, swinging back and to the bit. The horse is trained, from the beginning, to reach for the bit and accept contact. And he is, at the same time, trained to go forward in a clear and steady rhythm with relaxation and suppleness—the first two qualities in the Training Scale. Not to oversimplify, but if you have the first two qualities, then the development of contact has come along at the same time. And when the back is swinging, the connection between the hindquarters and the bit develops, too.

There are energy pathways of throughness: The horse thrusts from the left hind leg to the bit on the left and from the right hind leg to the bit on the right. These two pathways are unilateral. There are two other important pathways of energy that are diagonal: The energy can go from the left hind to the right rein when the horse is bent left, and the energy can go from the right hind leg to the left rein when the horse is bent right. Hence, the importance of riding inside leg to outside rein so the horse can balance on that outside rein. When the energy from the hindquarters reaches the bit and half halts return the energy to the hindquarters, then the rider has successfully connected the hindquarters and the forehand of the horse.

The horse is not allowed to lean on the bit, but rather he should carry it. When the contact is too strong and the horse is using the contact to carry some of his weight, the rider must half halt and/or do transitions with aids that encourage the hindquarters to step under and carry more weight.

Throughness Defined. Throughness is the supple, elastic, unblocked, connected state of the horse’s musculature that permits an unrestricted flow of energy from back to front and front to back, which allows the aids/influences to freely go through to all parts of the horse (e.g., the rein aids go through to reach and influence the hind legs).

Impulsion and Schwung

Impulsion is thrust or the release of stored energy. You can see that impulsion is related to rhythm, or the sequence of the footfall, because the release of stored energy happens only during the moment of thrust. In contrast, the moment of engagement is when the hind foot is flat on the ground, bearing weight with the joints bent or coiled as a spring. The moment of thrust or release happens right after that as the hind foot leaves the ground, sending the horse into a moment of suspension, in which all legs are off the ground. The walk doesn’t have a period of suspension, so it does not have impulsion. Instead, we refer to the comparable quality as “activity” in the walk. It should be active, but not hectic.

Impulsion is required in First Level, as you can see in “The Purpose of the Tests” sidebar on p. 27, and is most evident, or sometimes there’s lack of evidence, in the lengthening of the stride that is first required at First Level.

The German word Schwung (the fourth element of the German Training Scale) enhances the meaning of “impulsion” by focusing on the swing in the horse’s back. This swing of the back is evidence of a good connection between the hindquarters and the forehand. It provides the rider with the ability to sit with tremendous coordination and it enables the rider to enhance the gaits with timely aids. In fact, the Grand Prix rider can develop the shortened trot strides to piaffe by riding the horse’s back. The horse with a swinging back can be developed ideally.

You can, perhaps, see that the previous elements of the Training Scale, instead of being compromised during training, are being enhanced. The rhythm gets more cadenced, the suppleness is improved and the contact is more refined as the horse becomes more advanced in his training.

Straightness

Horses are naturally crooked because the hind legs do not innately track directly behind the front feet. Usually (but not always), the right hind foot steps to the outside of the right fore. Then the thrust from that right hind (which is too far to the right) pushes the left shoulder out, which makes the left rein heavy.

The tool for straightening horses is shoulder-fore, which isn’t exactly an exercise, because the wise rider is always trying to be in shoulder-fore. Shoulder-fore is simply riding straight. Even though Straightness is high up in the Training Scale, the rider must tend to it from the beginning. At Training Level, the judge will notice if the 20-meter circles to the left and right are not comparable. At First Level the judge will notice if the 10-meter circles are or are not comparable.

Shoulder-Fore. Shoulder-fore is simply riding straight. With slight flexion in the direction of travel (in this case the left), the rider narrows the left hind leg so it steps under the center of gravity—in the space between the two front legs. The rider prevents the right hind from going to the right as it is naturally inclined to do. The outside legs (right) are aligned and the inside hind is narrowed to the place in which it can carry the weight of horse and rider.

If the horse can easily do shoulder-fore left and right, he is straight and able to be in self-carriage at all times. In shoulder-fore the horse is balanced laterally—from left to right and right to left—and the work becomes very easy because the horse can relax when he’s in balance. When a horse is truly straight, he is also supple. Suppling work is straightening work and vice versa. The supple, straight horse

can collect.

Collection

According to the FEI Dressage Handbook, Collection is “the increased engagement and activity of the hind legs with the joints bent and supple, stepping forward under the horse’s body.” Those pushing hind legs take on the increased job of carrying, and the rider ideally has control over the ratio between the pushing and the carrying power of the hind legs. Collection is the goal in dressage and also in jumping as the horse has to carry 100 percent of his weight on the hind legs as he thrusts in the takeoff.

There are different degrees of collection, but in dressage it is first officially required at Second Level with shoulder-in, which is called “The Mother Exercise of Collection” because it introduces the concept.Collection can be developed by:

• lateral exercises beginning with shoulder-in,

• transitions that skip a gait (trot–halt–trot, walk–canter–walk), done smoothly with engagement,

• the rein-back used judiciously and

• half halts.

Ambitious riders who overuse their hands are taking a shortcut to the wrong destination, but riders who pay attention to every step in the Training Scale get collection on a silver platter! Collection just happens. It feels glorious and your horse will be as happy as you are.

Making Knowledge Useful

You might have noticed that one can actually have lots of knowledge, but it’s not particularly useful until you can organize it. When the filing system in your brain recategorizes certain bits of knowledge, suddenly—AHA! A concept that you thought you understood perfectly makes even more sense now, and you’re able to utilize it better because you see it in a different context. Let’s take Rhythm as an example. If you didn’t know that rhythm was an important part of the Training Scale, you know it now. You also know in the sidebar on the purposes of the test (see sidebar on page 27), that this quality is why you’re riding your Training Level test. Now here is a little bit of information about rhythm in other contexts

• In all dressage tests, from Introductory Level to Grand Prix, the gaits are judged on “freedom and regularity”—the regularity of the rhythm.

• When you ask a horse to increase his power (by adding impulsion), the rhythm becomes accentuated, and we call that “cadence.”

• Rhythm can be defined as the “characteristic sequence of footfalls,” and you can learn which hoof initiates, for example, the right canter lead (left hind). And it helps to learn what happens next and next, which leads to:

• Timing of the aids. There’s a specific moment—a window of time—within each sequence of footfall of walk, trot and canter during which you should apply the aids in order to get the desired result.

• In transitions between the gaits, the rhythm changes, but in transitions within the gait, the rider needs to help the horse maintain the rhythm and tempo. Without help, he’ll get quicker when the stride lengthens and slower when it shortens.

This could go on and on. The more you learn about rhythm in different contexts, the more you really know about rhythm. Grow your knowledge about each element in the Training Scale.

In summation, your success in implementing this Training Scale might depend as much on your persistence as it does on your knowledge and skill. Dressage Olympian Kyra Kyrklund once said that the difference between good riders and great riders is simply the fact that great riders are very particular about these basics. Others let them slide.

Germany’s Hubertus Schmidt once said, “Everyone knows how important it is to balance the horse on the outside rein on a 20-meter circle, but most people are too easily satisfied.” So if Hubertus Schmidt can spend his time refining those details on a 20-meter circle, so can we. So must we!