Sitting the trot is one of the big hurdles a rider has to face when moving up the levels in dressage. While learning to sit the trot may be easy for some riders, for most it presents a perplexing set of issues. The primary problem riders encounter when tackling the sitting trot is a lack of flexibility and movement in the hips. As anyone who has tried to salsa dance may have noticed, tight hips are a common problem.

As an Amazon Associate, Dressage Today may earn an affiliate commission when you buy through links on our site. Products links are selected by Dressage Today editors.

In my Pilates practice, most of the clients I have worked with—riders and nonriders alike—have this same issue. When a rider has tight hip joints, following the horse’s movement in every gait is difficult. But rigid and tense hips especially impede the rider’s ability to sit the trot because this requires a quick pulsing action of supple, loose hip joints opening and gently closing in a fluid and rhythmic fashion.

While it may not be obvious, following the motion of the horse’s back in all gaits requires the same flexibility of the hips. But while a rider might be comfortable at the walk and canter, easily sitting the trot often feels out of reach.

In this article, I will briefly explain the mechanics of the hip joint and give you two Pilates-based exercises to help you find, isolate and loosen your hips. Practicing these exercises will help you learn how to truly follow the horse’s movement at any gait.

Once your hip joints allow your thigh bones (femurs) to move freely in their sockets while you keep your pelvis and lower back stable, sitting the trot will become easy.

Let’s Look at the Pelvis

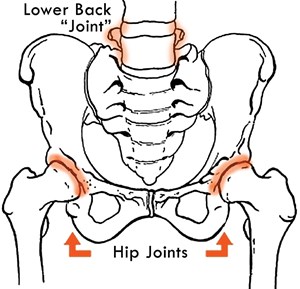

Your pelvis is an immobile bony structure that has joints at both the top and bottom. The top joint is where your spine connects into the pelvis at the lower back. At the base of the pelvis are the hip sockets, one on each side of your pubic bone. The attachments of the femurs into these sockets are your hip joints. The ball-in-socket hip joints at the bottom of the pelvis are similar to your shoulder joints. But all you need to do is move your arm around in all directions and then try that with your leg to notice that your hip joints do not have the same mobility.

While riding does not require that your hip joints be as flexible as your shoulder joints, being able to move the femur forward and back in the hip socket with ease without disturbing the pelvis and torso is key to riding and sitting the trot.

To ride all gaits correctly, the junction of the spine meeting the pelvis at the lower back must be stabilized while the hip joints at the bottom of the pelvis must be mobile. If a rider has tight hips, the lower back inevitably takes all the motion of the moving horse. When this happens, not only will the hip joints tend to lock up, the rider will probably also eventually experience lower back pain. To avoid this, the rider must learn to stabilize the joint at the top of the pelvis (lower back) with the abdominal muscles. This stabilization creates an upright pelvis and torso, which will be carried forward in space when riding by the motion of the horse’s back.

When your abdominals create a stable lower back, the hip joints at the bottom of the pelvis can become the shock absorbers when riding. When the musculature of the hips is balanced, meaning all of the muscles that connect to the ball of the femur are equally strong and flexible, the hips will be supple enough to absorb movement.

The most common muscular tightness in the hip joint is located in the front of the hip. These tight muscles are your hip flexors, which function to close the hip-joint angle and bring the femur forward. This tightness is what causes a “chair seat” for the rider. The ability to open the hip is much more difficult because of this tightness. Just think about what people do in daily life: mainly walk forward and sit, both of which create a more closed hip joint. And because we rarely walk backward or extend the femur behind the pelvis, the hip is often unable to open and, therefore, the hip extensors are weak. Addressing this imbalance is key to loosening the hips.

Loosen Those Hips

Learning to loosen your hips is actually simple but requires some thought and practice. First, the abdominal muscles must hold the pelvis and lower back stable while the hip extensors draw the thigh bone back. The following exercises will teach you to do this.

The Exercises:

Walk Backward

1. Pace off the barn aisle so you know how many steps you can take safely.

2. Stand with your back facing the aisle and pull your lower abdominals in and up. Ideally, you will feel the pubic bone rising slightly toward your rib cage and your lower back will lose its hollowed curve.

3. Begin to walk backward slowly. As you take your femur behind your pelvis, keep re-engaging your lower abdominal muscles to hold your pelvis upright and keep your lower back from hollowing.

4. Take as many backward steps as you have previously paced off. You may notice that your ability to take your femur backward is much more limited in scope.

When walking backward in this frame, you should feel your bottom muscles and hamstrings work while the front of your hip will feel a stretch. (The tighter your hips are, the more you will feel this work and/or stretch.) This is a good first step toward loosening the front musculature of your hips. The next exercise is a little more challenging.

Dance With a Doorjamb

1. Stand with your back in a doorway.

2. Place your torso flush with the doorjamb: Pull your lower abdominals in and up and stretch out your lower back to rest along the jamb, so that three-quarters of your pelvis is on the jamb. You will feel the hip extensors begin to engage.

3. Place your weight on your left foot.

4. Keeping your lower back on the wall with your engaged lower abdominals, move your right leg behind you (as in a canter aid or a tango step) without allowing the lower back to come off the jamb.

5. You will feel a big stretch across the front of your hip and it will take a huge effort to keep your pelvis/lower back on the doorjamb. Do the best you can.

6. Hold for 10–30 seconds and repeat on your left leg.

This exercise will help you isolate and stretch the front of the hip by using your hip extensors. You may find one hip tighter than the other. If so, repeat the exercise on the tighter side. You can now imagine how the tightness in the front of the hip can impede the joint’s ability to move easily as needed for riding. The wall will give you great feedback as to whether or not you are strong enough in your core abdominal muscles to hold your pelvis upright for a independent seat and leg.

Experiment on Your Horse

After practicing both of these exercises, your hips should feel more open in the front of the joint. Now that you have loosened up your hips, try this experiment on your horse. When you first get on you might notice that your stirrups feel too short. If they are, drop them as needed.

1. Engage your lower abdominal muscles and draw your pubic bone up to lengthen and stabilize your lower back. When you do this you will already feel a stretch in the front of the hip.

2. As you walk around in your warm-up, notice what your hip joint and lower back are doing. First, check to see if your lower back is staying stable and that your hip joints are actually opening and closing in a gently pulsing action. To test that, hold your hip joint tight, don’t let it move, and see how this feels.

3. Now let go and notice the change.

4. Keep reminding yourself to keep your lower abdominals engaged to stabilize the lower back so the pelvis remains upright and the hip joints will be the part of your seat to follow the motion of your horse’s back.

5. Now actively create a light pulsing motion with the lower abdominals lifting the pubic bone while the hip extensors activate the back of the hip (pulling the femur slightly back) and release. This will allow your hip to gently open and close with each step of your horse.

While you do this exercise, be sure to notice how it feels when you hold the front of the hip tight; it closes the joint and actually draws your knees up. When you activate your lower abdominals to stabilize and stretch the lower back, you can feel the hip extensors pulse with every step. Finding the front of the hip open with the back of the hip working, you can feel that you can easily drop the weight of your leg down the sides of your horse into the stirrup.

Sit the Trot

Once a rider can achieve this stability in the lower back in combination with fluidity in the hip joints, the next challenge is to be able to maintain that while riding the horse’s different rhythms and tempos.

The first step is to practice at the walk for a few days, focusing on the gentle opening and closing of your hips in the four-beat rhythm of the walk. The sitting trot is nothing more than a double-time of that rhythm.

The increased tempo does make the exercise more challenging. But this ability to fluidly open and close the hips with a stable lower back is the key to your sitting-trot success.

Janice Dulak is a Master Pilates Instructor through Romana’s Pilates. She has been riding dressage for more than 10 years and is the author of the book Pilates for the Dressage Rider and the DVD “Nine Pilates Essentials for the Balanced Rider.” She lives with her husband on their Amber Waves Farm near Champaign, Illinois, and they winter in Reddick, Florida. Visit dulakpilates.com.